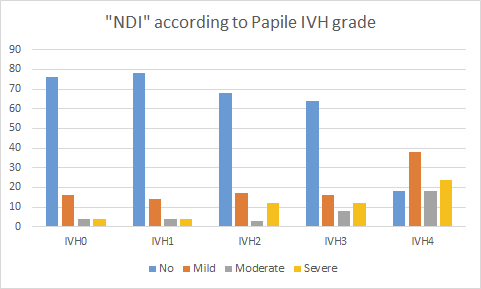

Despite the evidence that “NDI” is of little interest to parents, we continue to focus on it in outcome studies, and even equate it with death.

Unfortunately, this new study, using the substantial resources of the NICHD NRN and their enormous database asks the question what happens to “death or NDI” according to the use of postnatal steroids? (Jensen EA, et al. Assessment of Corticosteroid Therapy and Death or Disability According to Pretreatment Risk of Death or Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2312277).

If you are going to combine outcomes like this, they should surely be of somewhat similar importance. I think everyone would find it ridiculous to ask what is the incidence of the outcome “death or sleep disturbance”, or perhaps “death or halitosis”.

If I needed a colonic surgery, and the surgeon told me there were two different surgical approaches, one gave a risk of “death or colostomy” of 30%, whereas the other had a risk of “death or colostomy” of 20%, but didn’t tell me what the risks for each individual part of that outcome were, I think I would be angry! I would certainly want to know which approach gave me the greatest risk of dying, and what were the likelihoods of a colostomy after each surgery. Even if I was appalled at the idea of having a colostomy, it would take an enormously greater chance of having a colostomy to outweigh a modest increase in the probability of dying; but that should surely be my choice to make, and I could not make the decision without knowing of the size of the two risks, individually.

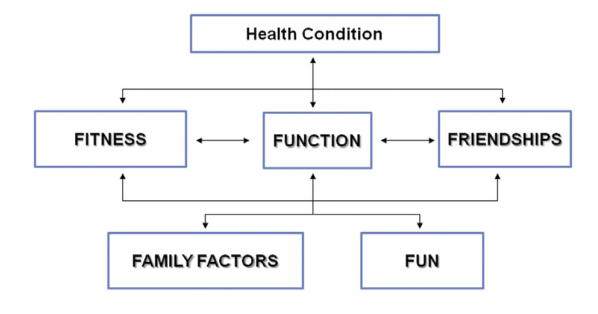

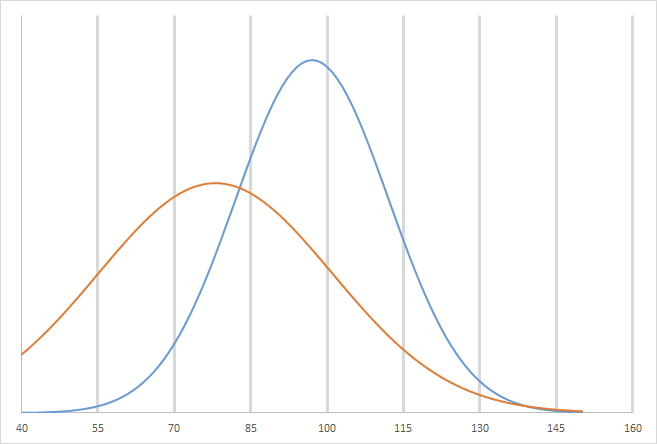

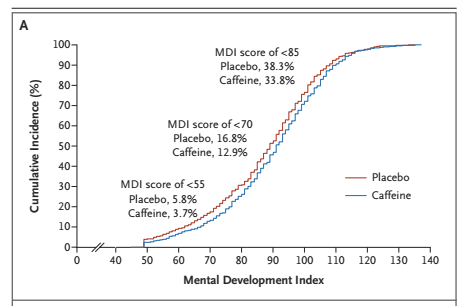

In this new publication what they call NDI (or even worse, in the title and the figure titles, just “disability”) is either cerebral palsy, or a score on the BSID version 3 of <85 on either the cognitive or motor composite. I refer you back to my most recent post, which describes a study recounting, in scenario form, what a score <70 on those scales represents, of course, a score of <85 is a much less important finding, and probably has no impact on the infant’s life of any significance. To equate that with death seems to be… questionable. To recount briefly what that other study (which is open access) showed, respondents almost universally did not think a scenario describing a child with a BSID3 language, motor, or cognitive composite score <2 SD below the mean was a severe health problem. Nevertheless in this new article, an infant with a motor or cognitive composite score <1 SD below the mean is classified as having “moderate to severe NDI”.

The question, which is an important one, is when it is appropriate to consider the use of postnatal steroids.

Does anyone ever sit down with a parent to tell them about the combined risk of either dying or having a BSID 3 cognitive or motor score more than 1 SD below the mean? It probably does sometimes occur that someone in the care team will talk vaguely about the risk of “dying or being very handicapped” but a low BSID3 score does NOT equate to disability, or impairment, or handicap! It is a sign of a developmental progress below the average of a standardized population norm, that is all. It can be a useful evaluation of current developmental progress, but it is NOT A DISABILITY.

But, surely, the important question is not “what is the use of PNS at this stage for this baby likely to do to their risk of “death or NDI”? The question should be, what is the likely impact on death, and, if the baby survives, is this use of steroids likely to adversely impact their development or motor function at long term, and by how much?

I don’t think there has ever been a study that showed improved developmental or motor outcomes with the use of postnatal steroids. They have all, to my knowledge, shown either no effect, or adverse impacts. Some analyses have shown that steroids may decrease mortality, when used in groups at high risk of dying.

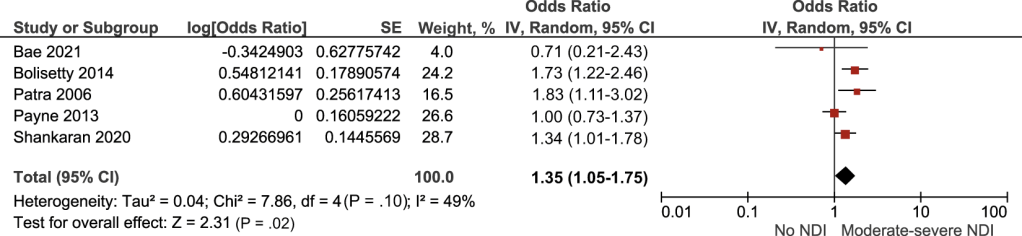

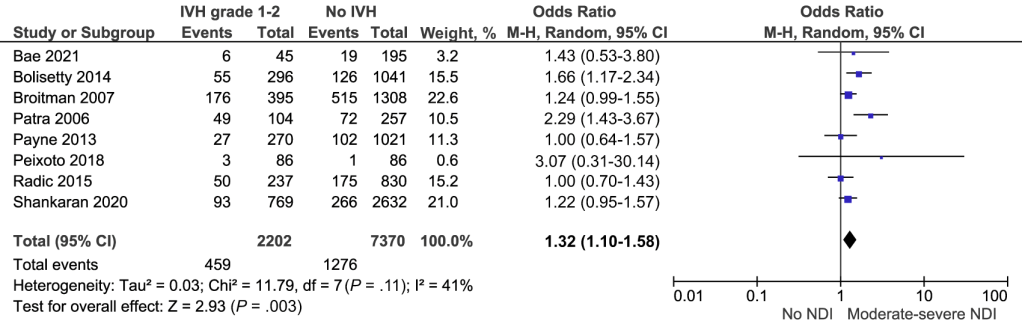

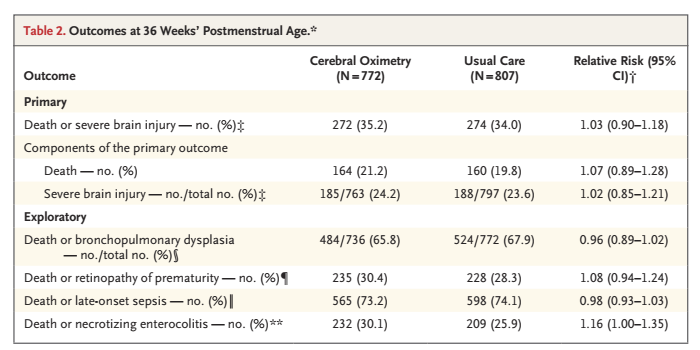

I think it is likely that use of steroids when the infant is a low risk of death will probably have little effect on mortality, and may expose them to the adverse developmental impacts, whereas, when the risk of mortality is high there may be mortality benefits, and the adverse developmental effects become of less importance for decision-making. One of Lex Doyle’s studies was a meta-analysis of steroid use and death or long term developmental/neurologic impacts, that study showed that trials which examined the use of steroids given early did not improve mortality but when given later there was a tendency to a reduction in mortality, CP was increased by steroids in both groups of studies, but was increased more in the early treatment trials.

A similar analysis could have been a useful result of this study; to show separately the associations between postnatal steroid use and mortality, according to risk profile, and then also the association with both developmental progress and CP among survivors.

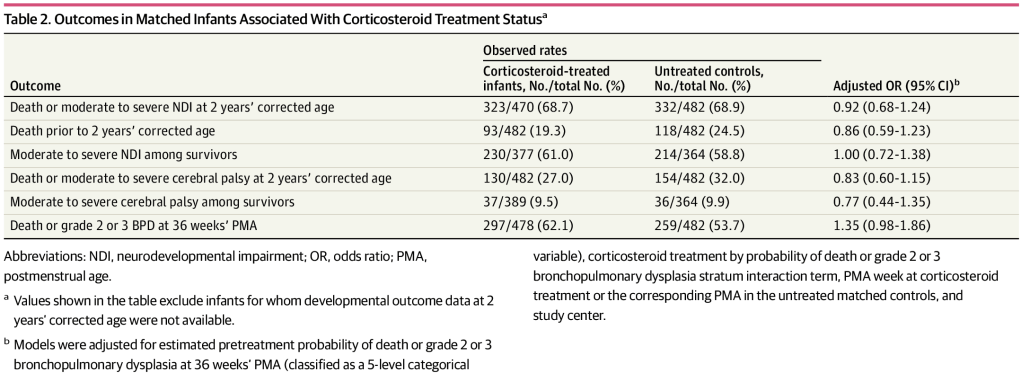

As we don’t have that, we can make a few observations: of note, the total dose and/or duration of steroid use are not in the database, just the date of initiation and type of steroid (dexamethasone or hydrocortisone). The analysis was restricted to babies whose steroids were started between 8 and 42 days of age. Using propensity score matching, the babies were matched with others who never had postnatal steroids.

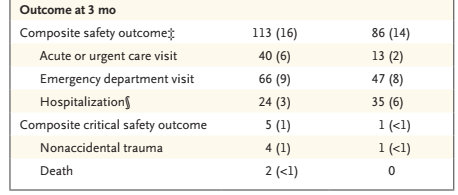

As you can see, the babies were at high risk of dying and at high risk of needing oxygen or respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA. What they call “moderate to severe CP” is CP with a GMFCS of 2 or more. Again, of note, parents do not consider CP with a GMFCS of 2 or 3 to be a significant health problem, and adults with CP evaluate their quality of life, using validated scoring systems, as identical to controls.

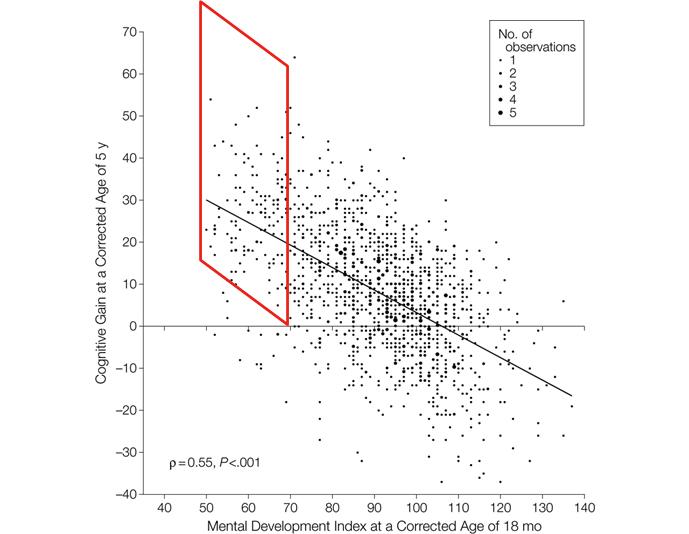

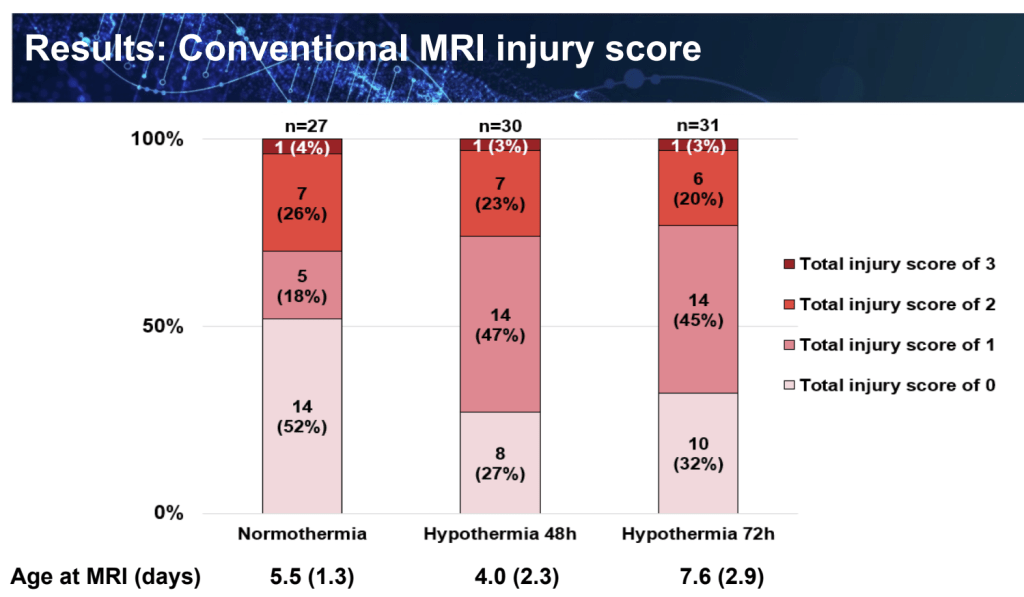

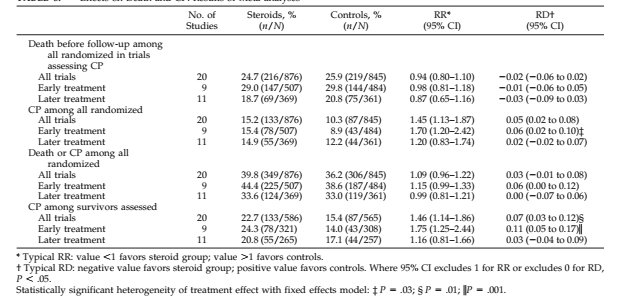

There are multiple graphs showing the correlation of risk for “death or BPD” with risk of “death or NDI” or with “death or CP”, but as none of them show what the impact is on death, we have to assume that the lower risk of “death or NDI” (as shown in the figure below for example) is probably mostly a lower risk of death. Maybe the greater benefit of starting hydocortisone is because there were fewer kids with “NDI” after hydrocortisone use than with dexamethasone use, or maybe it is better at preventing death. Who knows? You cannot tell from this publication.

Of note, a baby who was initially treated with hydrocortisone, then switched to dexamethasone would be classified as a hydrocortisone treated baby in this figure.

Unfortunately, there are no data in the publication or in the supplemental data to help anyone making a decision about steroid treatment in an infant with evolving chronic lung disease.