Babies with established BPD (I won’t worry about the exact diagnostic criteria here, but very preterm infants who are still ventilated as they approach term are the group I am talking about) have somewhat reduced compliance, increased airways resistance, leading to long time constants, and rather heterogeneous lungs, often with apical emphysema and basal atelectasis. Ventilatory requirements are different to infants with, for example, HMD, who have predominately atelectatic lung disease, very low compliance, and airways resistance which is largely normal, apart from the resistance due to the endotracheal tube; such infants have very short time constants, so can be ventilated with very short expiratory times, and respond to increased PEEP with improving oxygenation. The limit of PEEP in such infants is when airway pressures are high enough to interfere with venous return, something which changes dramatically after surfactant administration, following which overdistension of the lungs is a risk to be avoided by rapid weaning of PEEP.

Selecting the optimal PEEP, respiratory rate, inspiratory/expiratory times and tidal volumes in established BPD is often tricky. The goals are to minimize on-going lung injury, maintain adequate oxygen delivery, and progress toward non-invasive support. Determining lung volumes is not easily done at the bedside, chest-xrays are insensitive, and may show both overdistension and atelectasis on the same image.

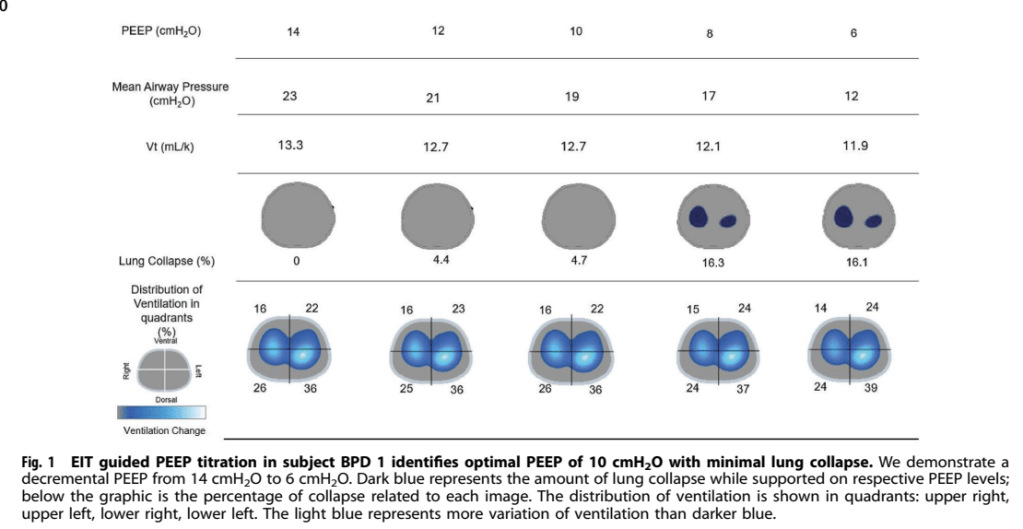

Shui JE, et al. Identifying optimal positive end-expiratory pressure with electrical impedance tomography guidance in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2026. In this small study the authors used ventilation measurements from Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) during changes in PEEP to determine what PEEP led to the best ventilation without over-distension or atelectasis. BPD infants were very sick babies of 43 to 54 weeks PMA, they were on PEEP between 10 and 14 and mostly in a lot of of oxygen (one post-tracheotomy was in 25-30%).

The EIT belt is placed around the chest of the infant, as far as I can tell sedation and/or paralysis were not changed during the measurement, and PEEP was varied up or down over a total of 1 to 2 hours.

After processing, the EIT gives results like these. I’m not sure I understand what they mean by “variation in ventilation” which determines the shade of blue in the lower panel, and which is also called “ventilation change”

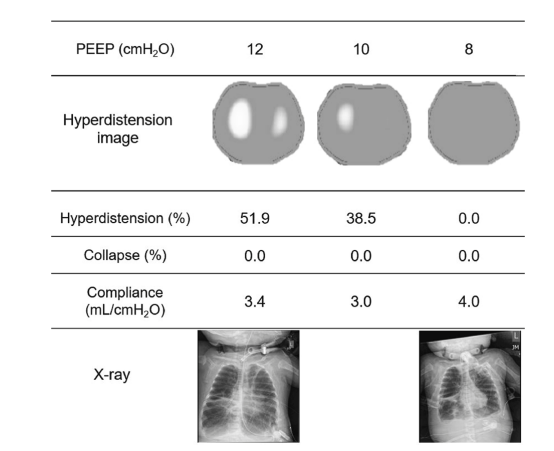

One thing you can see from the figures, and from the supplemental data, is that the dynamic compliance is at its highest when the infant is placed on what the determine from EIT to be the optimal PEEP. For the infant in the figure above for example, the compliance is 2 mL/cmH2O at a PEEP of 14, 2.3 at a PEEP of 10, and 1.8 at a PEEP of 6.

Another figure in the article, from a different patient, with x-rays included, again shows that the dynamic compliance is greatest at optimal PEEP.

Perhaps the EIT isn’t necessary, and one could do the same procedure just calculating the compliance at each step.

It would be nice to have a larger case series, and to compare different methods of determining optimal PEEP, but I think this might turn out to be a very useful technique. I’ll have to figure out how to get hold of one.

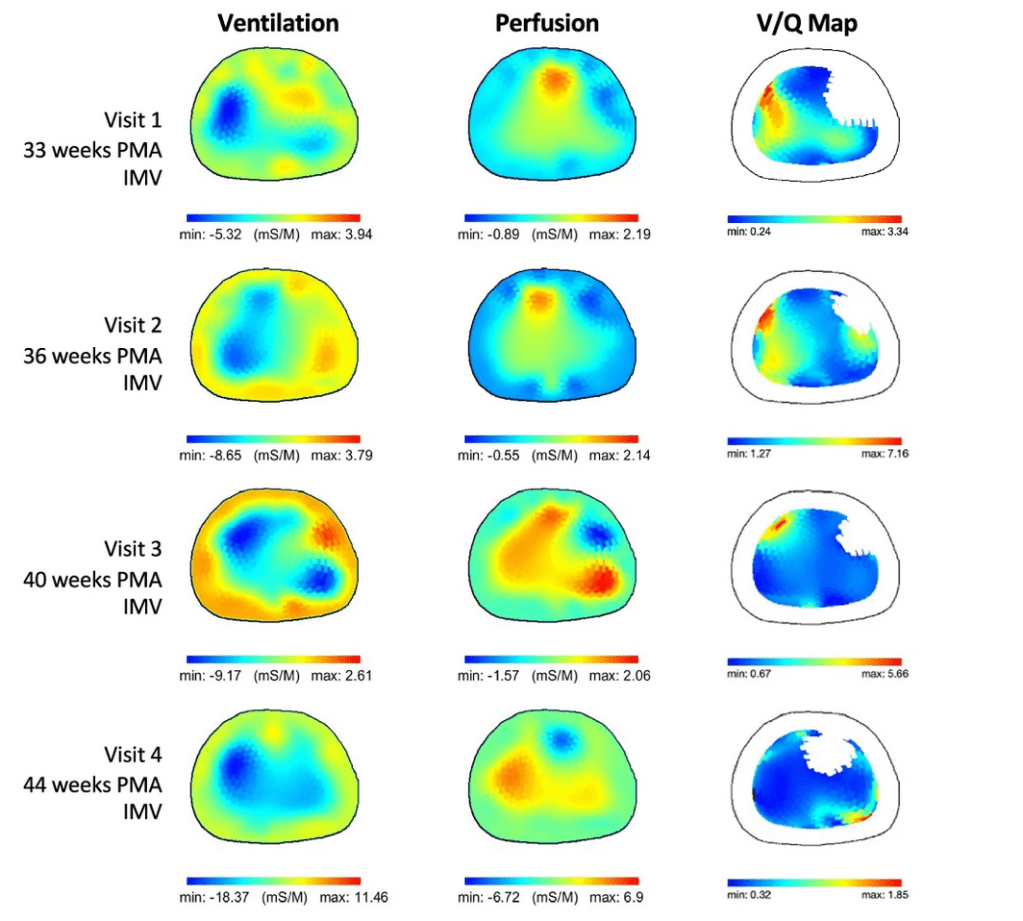

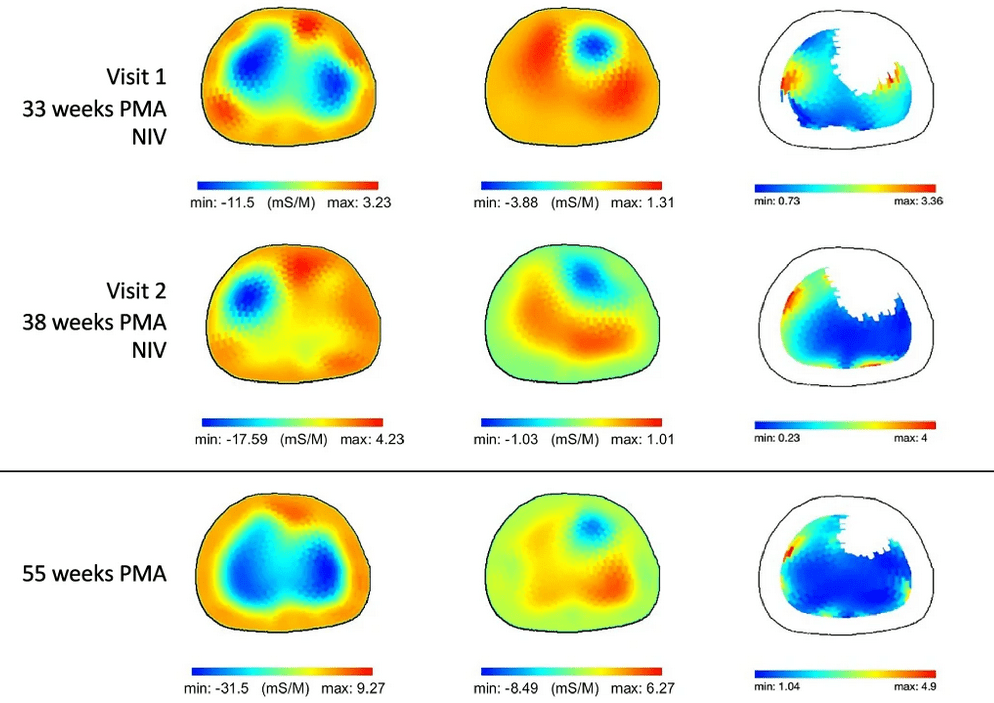

EIT can also be used to image perfusion of the lung,s as the amazing David Tingay, and his coworkers, demonstrated a few years ago (Tingay DG, et al. Electrical Impedance Tomography Can Identify Ventilation and Perfusion Defects: A Neonatal Case. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(3):384–6). There had been little follow up of that article until 2 publications from the same authors, from Aurora Colorado, one is a case report of repeated EIT in a single complex case, which has some fascinating videos in the supplementary materials (Enzer KG, et al. Electrical impedance tomography imaging of ventilation and perfusion in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 462026. p. 284–6) The other is a case series, which just appeared on-line with images from repeated EIT studies from infants with varying severity of BPD, and some controls. The images below are from an infant with severe BPD (still ventilated at 44 weeks PMA).

The bars below the images show the colours attributed for ventilation, or perfusion, or the ratio between Ventilation in litres/s and perfusion (Q) in litres/s. We don’t know the details of how the baby was being ventilated, but there seems to be a progressive improvement in V/Q matching over the studies.

The following figure shows results from 2 studies of an infant with mild BPD, and at the bottom a control infant. The second images of the BPD infant show ongoing differences from the control, but the VQ pattern looks almost normal, to my untrained eye.

I think this is the only non-invasive way of getting a V/Q image of the lungs, which might turn out to be very useful, if it can be rolled out with a simple to use commercial device.

I suggested, in response to the first paper, that the optimal PEEP might be determined without EIT by determining the PEEP which gives the highest dynamic compliance. That is exactly what these authors seem to have done in a group of babies with developing or established BPD who were ventilated. They had a protocol for varying the PEEP, after paralysing the infants with vecuronium, and giving them sedation. (Darwish N, et al. A non-invasive diagnostic tool for the assessment of optimal positive-end expiratory pressure (PEEP(OPT)) in infants receiving prolonged invasive ventilation. J Perinatol 2026).

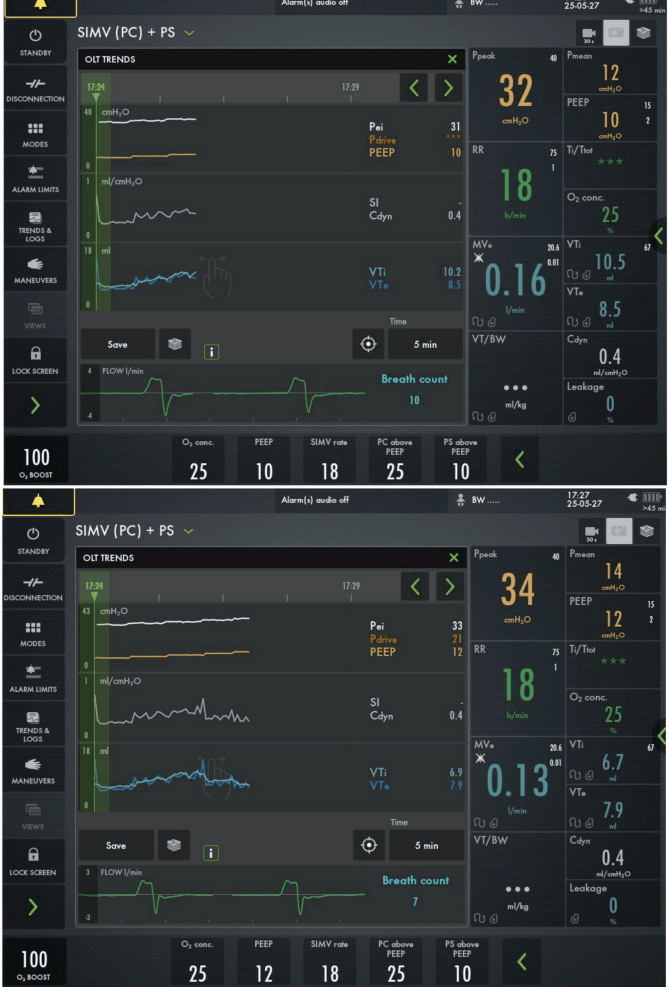

Unfortunately the figure they use doesn’t really do the article justice, as it shows the same dynamic compliance (Cdyn on the photo of the ventilator screen shown below) of 0.4 at each of the 2 PEEP levels shown in the 2 panels

But if you look at the 2 lines in the middle of the lower screen, the one in orange, showing the PEEP, and the one below in white, showing the compliance, you can just make out the stepwise increases in PEEP, and that the Cdyn seems to increase up to a PEEP of 10, then drops at the PEEP of 12.

Of course, if you have a paralysed patient, and you keep the delta-p constant, you don’t need to calculate Cdyn, you can just measure the tidal volume; the expired Vt dropped from 8.5 to 7.9 with the increase in PEEP from 10 to 12 (the Cdyn fell from 0.41 to 0.38 with that increase in PEEP, the numbers on the screen are given as a single decimal point, which is why you don’t see any change).

Calculating Cdyn, or interpreting tidal volume changes are much trickier in an infant who is breathing, as respiratory effort is very variable in our babies, you would really need to wait until the infant was apneic, or perhaps do a recording and average over a long period of sleep cycles and variable activity. I guess it is probably acceptable to use a medium-duration muscle relaxant in this way, if there is a good chance you can optimise assisted ventilation. Most of the infants in this publication had a change in their PEEP (either up or down) indicated by the study.

An alternative would be to insert an oesophageal catheter and measure the trans-pulmonary pressure, if you have the equipment and the expertise. Then you wouldn’t have to paralyse the infant.

I think it is likely that increases in PEEP which lead to decrease in Cdyn are evidence of over-distension, which is probably also the point at which there will be a circulatory impact of the positive intrathoracic pressure. Finding optimal PEEP should help to be able to ventilate these babies with less adverse effect, and optimal lung inflation.

What is the best way to find the optimal PEEP I am not sure, but the EIT technique was performed without paralysis, and they were able to find the PEEP that gave the highest compliance. Whether the EIT signal really adds to that process I am unsure.