Yet another trial of PDA treatment and attempted closure with a null result.

Baby-OSCAR was a UK multi-center masked RCT of ibuprofen treatment of 23 to <29 week infants who were screened with echocardiogram within the first 72 hours of life, and randomized if the PDA diameter was >1.5 mm (Gupta S, et al. Trial of Selective Early Treatment of Patent Ductus Arteriosus with Ibuprofen. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(4):314-25). The echo criteria included the need for pulsatile left-to right shunting and no evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

There were few other eligibility restrictions. 3861 babies had echocardiograms for determining eligibility and 1271 had large enough PDA to be eligible, most of the failure to enrol was parental refusal, and the groups were well balanced, with a final sample size of 653.

The primary outcome was the dreaded “death or BPD”, meaning an oxygen requirement at 36 weeks or death before 36 weeks, babies who did not require oxygen after an O2 reduction test were considered “mild BPD” and not considered an adverse outcome. Babies on high-flow cannulae with 21% O2, however, were all considered to have severe BPD and did not have an O2 reduction test.

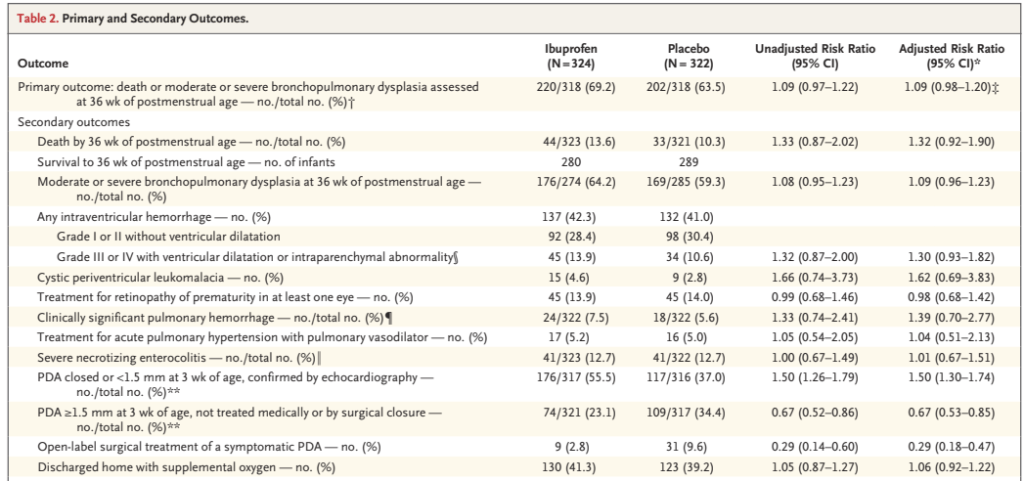

The primary outcome was not different between groups; the major outcomes are shown below:

As you can see there were more adverse outcomes in the ibuprofen group for just about every outcome.

I don’t understand, yet again, why mortality is only reported up to 36 weeks. There are no data I can find anywhere in the publication or supplemental materials about overall mortality. The results presented don’t, as a result, answer the most important question of all, “does early ibuprofen treatment of a large PDA have an effect on survival?”

You can’t even back-calculate survival to discharge from the home oxygen numbers, as 130 ibuprofen babies went home in oxygen, which is reported as being 41.3%, but that can’t be quite right; 130 is 41.3% of 315, which is less than the number randomized in that group (324), but is greater than the number of 36 week survivors (280). Perhaps 35 babies were resurrected after 36 weeks, and went home without oxygen? Similarly 123 control babies went home on oxygen, which is reported as being 39.2%, giving a total number of babies discharged of 314, but only 289 survived to 36 weeks.

All we know about mortality, therefore, are the numbers who survived to 36 weeks, and we have to hope that there wasn’t an imbalance of deaths between 36 weeks and discharge. According to the supplemental data, two secondary outcomes were determined at discharge, NEC and home oxygen, so the denominator, alive at discharge, should surely have been reported.

By the protocol of the Baby-OSCAR trial, open label treatment with ibuprofen could be given if the following were present:

- Inability to wean on ventilator (ventilated for at least 7 days continuously) and any of: inability to wean oxygen; persistent hypotension; pulmonary haemorrhage; signs of cardiac failure

AND - Echocardiographic findings of a large PDA (PDA ≥ 2.0 mm with pulsatile flow) AND

- Echocardiographic findings of hyperdynamic circulation or ductal steal (refer to Baby-OSCAR ECHO workbook).

I’m not sure what “signs of cardiac failure” means, I haven’t seen a definition in the protocol. There were 15 ibuprofen and 33 controls who received open label treatment without satisfying these criteria. In total 14% of the ibuprofen-treated and 30% of the controls received open-label treatment including both the by protocol and outside of protocol open-label use, the timing of which is shown in this survival graph

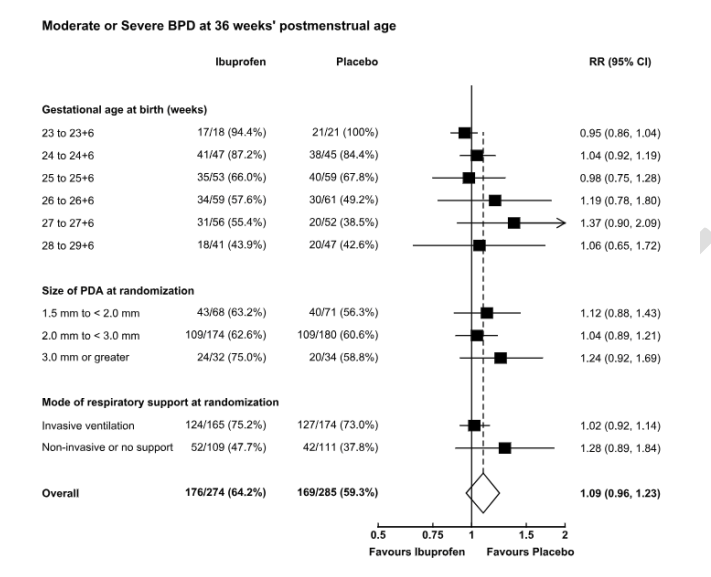

Despite the limitations of the design and the study report, there is no evidence of any benefit of early ibuprofen treatment of PDA of over 1.5 mm diameter, compared to selective later treatment. Subgroup analysis of the larger ducts, the babies receiving assisted ventilation, and by gestational age show no group with a benefit in either BPD or death. The most immature babies almost all have BPD, and there is therefore no difference in their primary outcome.

Much like the Beneductus trial there was actually more BPD in the treated group, a relatively minor difference in this trial, and a larger difference in that other trial, which otherwise has a number of similarities to Baby-OSCAR. Both required a PDA >1.5 mm diameter within 72 hours of birth, without signs of pulmonary hypertension. The average GA in each study was 26.1 weeks (even though Baby-OSCAR included 28 week babies, and Beneductus was <28 weeks, probably because there were more 23 week GA babies in Baby-OSCAR). One big difference with Beneductus, is that only one control infant had open-label PDA treatment in that trial, and with less cross over they showed a greater difference in BPD. Need for home oxygen is a much more clinically important outcome, and it seems to me to be very high among the babies in this trial, at about 40%, but was almost identical between groups.

The editorial accompanying the trial publication notes that there is very little evidence of any situation in which medical or surgical PDA closure improves clinical outcomes. However, it also includes the following “With more than half of the enrolled patients born at less than 26 weeks’ gestation and an absence of notable serious adverse events, early parenteral administration of the drug appears safe in this high-risk population and may ultimately reduce the need for surgical or transcatheter closure”. Which I think is a bizarre statement. Surely, if there is no apparent benefit, the fact that it is “safe” is irrelevant, even if it were true. And, even though I am very critical of the use of BPD as a measure of lung injury, the results from these 2 recent trials show an increase in BPD. The two previous trials of ibuprofen in the Cochrane review of early PDA treatment, in the subgroup of “very early treatment” (<72 hours of age), only included a total of 128 babies, one of which was a trial in China of oral ibuprofen, the other being Afif El-Khuffash’s pilot trial with 60 babies. Those two studies showed a possible decrease in “Chronic Lung Disease”, but are overwhelmed by the results from these 2 latest trials, which suggest that early ibuprofen treatment is not safe.

The editorial also begs the question of what is a “need” for surgical or transcatheter closure. Across Canada in the last 10 years, the percentage of babies <33 weeks who have had a surgical PDA closure has fallen from 3% to 1%, and among those who have a recorded diagnosis of a PDA has fallen from 10% to 4%. The best way to avoid surgical PDA closure may well be to just avoid surgical PDA closures.

One potential benefit of early PDA closure from previous studies was an apparent impact on pulmonary haemorrhage. Martin Kluckow’s trial of early indomethacin treatment showed a reduction in this serious phenomenon. The results of this new trial show no benefit for this outcome, the haemorrhages just look like they tend to occur later. The first column below is the ibuprofen group, the 2nd column are the controls, there were a few more pulmonary haemorrages in the ibuprofen group (blood in the endotracheal tube with a respiratory deterioration), and they occurred later.

You could also ask if having the pulmonary haemorrhage later might be a benefit, as the serious intracranial haemorrhages, which often occur at the same time, might be less frequent if the pulmonary haemorrhage occurs after day 3 to 6, but as the main table of the results above shows, there were actually a few more serious intracranial haemorrhages with ibuprofen than with control.

As far as I can tell then, trying to integrate these new data into the large literature that already exists, there is no clinical situation in which using medication to close a patent ductus arterious has been shown to improve clinically important outcomes.

The most evidence-based approach to the PDA therefore, appears to be to just to leave it alone.

It is possible that there exist clinical situations in which closure of the PDA is justified, but I think it is incumbent on anyone who thinks that is true to perform studies to prove that you improve clinically relevant outcomes with treatment in those situations. It may be, for example, that babies with a large duct with a large difference between left and right ventricular outputs and diastolic steal in the abdominal aorta would benefit from ductal constriction with early ibuprofen treatment, even though it is not very effective in closing the PDA.

But there are currently no subgroups in whom treatment has been shown to have more benefit than harm. Perhaps this lack of benefit is because ibuprofen is not very effective, but the only other options would be to either return to indomethacin, which is not much different in efficacy, or to routinely close by catheterisation or surgery. Those options are not realistic for the large majority of sick tiny preterm infants.

There are already centres who have decided to rarely, if ever, treat the PDA. In Montreal, for example, we have a difference in treatment approaches between our hospital (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte Justine, CHUSJ) and McGill, where they have decided to be extremely conservative, and have progressively reduced their rate of PDA treatment to close to zero. The two groups have just published some long term follow up results of babies <29 weeks, (Cervera SB, et al. Evaluation of the association between patent ductus arteriosus approach and neurodevelopment in extremely preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2024) over the period of the study, 2014 to 2017, the rate of PDA treatment fell from 33% to 0% at McGill, and remained much higher at CHUSJ. The new publication reports the neurological and developmental outcomes, which are close to identical between the 2 centres. Among the large number of comparisons the only one which is a bit different is the mean motor composite score, but the proportion with scores below various thresholds were identical, and all the cognitive, visual and other outcomes are very similar. The shorter term results show there is somewhat more BPD (using the usual diagnostic criteria) at CHUSJ, despite a much higher rate of PDA treatment, which was almost all with ibuprofen; over the years of that study we also had a 6% rate of PDA ligation, which has since fallen to about 0.

As mentioned above, there appears to be no longer any evidence-based indication for ibuprofen use to treat the PDA. Despite large numbers of trials, and multiple different attempts to determine whether we can improve outcomes with ibuprofen, or with acetaminophen/paracetamol, I am left wondering in what circumstances treatment is justifiable.

There will probably be other trials, and I would guess they will have to include older infants with persistent very large shunts, and will examine effective ways of closing the PDA, such as by catheterization. For now early treatment with ibuprofen appears to be relatively ineffective in closing the PDA, ineffective in improving any clinically important outcomes, and appears to lead to worse pulmonary outcomes. It will be essential to find out what the impact on mortality was in the Baby-OSCAR trial, and more clinically important respiratory outcomes.

Thank you Keith another wise and thoughtful piece about treating PDA and the possible lack of benefit.

For a while I have been aware that we used to diagnose a PDA because we could hear a murmur. Without our stethoscopes our concern might have been much less. Then we moved into the era of ultrasound and could measure the size of the DA and the blood flowing through it. Without those images and measurements probably would not have been so concerned about any PDA and not have wanted to submit such babies to serious surgery or even drugs.

Just because we could hear and see a PDA does not mean that it needed treating. The arguments for treating the PDA was that it was a major contributor to BPD. We now know that there is a strong association between a being very premature and having a PDA with BPD rather than the PDA being a major cause.

best wishes

Colin Morley

Pingback: PAS report 2024: Clinical Trials part 1. | Neonatal Research