I have written many times about the problems with classical composite outcomes in neonatal research. “Death or BPD”, “death or NDI”, or sometimes “death or NEC or Sepsis or BPD or severe IVH” have been used as a way of combining adverse outcomes that we want to avoid, and accounting for the fact that death is a competing outcome for many negative outcomes. The enormous problems with such composites is that they give equal weight, when evaluating an intervention, to the components of the composite. A baby who survives to 36 weeks but needs oxygen is considered equivalent, in terms of the analysis of the results, to a baby who dies.

This has led to a number of serious problems in interpretation of results, to the extent that interventions may, for example, decrease mortality, but if they have no impact on BPD the results may be considered null and “not statistically significant”. Composite outcomes have sometimes been used as a way of increasing power, but in reality they do not necessarily increase power. Especially if the components change in different directions, or if the most important outcome is less frequent than the less important components; in such instances power may actually be decreased.

I have suggested, in the past the Win Ratio approach, one way of planning and analyzing trials, in which outcomes are evaluated in a prioritised fashion, and death is considered the worst outcome, followed by survival with very severe BPD, followed by survival with less severe BPD… etc. Subjects can be compared in pairs to see which has the better outcome, this Win Ratio approach has been used in some trials, especially in adult cardiology studies. It is an approach which is most easily used if subjects are randomized in pairs. In more standard large RCTs, each subject in group 1 has to be compared to every subject in group 2, and the maths and the statistical analysis becomes more complex.

An alternative which has been used mostly, I think, in infectious disease research, is called the Desirability Of Outcomes Ranking. This article, for example, discusses how to design and analyze a trial using this approach (Ong SWX, et al. Unlocking the DOOR-how to design, apply, analyse, and interpret desirability of outcome ranking endpoints in infectious diseases clinical trials. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023;29(8):1024-30). It was designed as a way of analyzing trials where there are a few deaths, some patients survive with complications, and others survive without serious complications. Ranking these outcomes according to their desirability. Exactly how to rank the outcomes, which also include, for example, treatment failure where the antibiotics don’t eliminate the infection, is an ongoing question, but should include important input from patients, or in our case, parents.

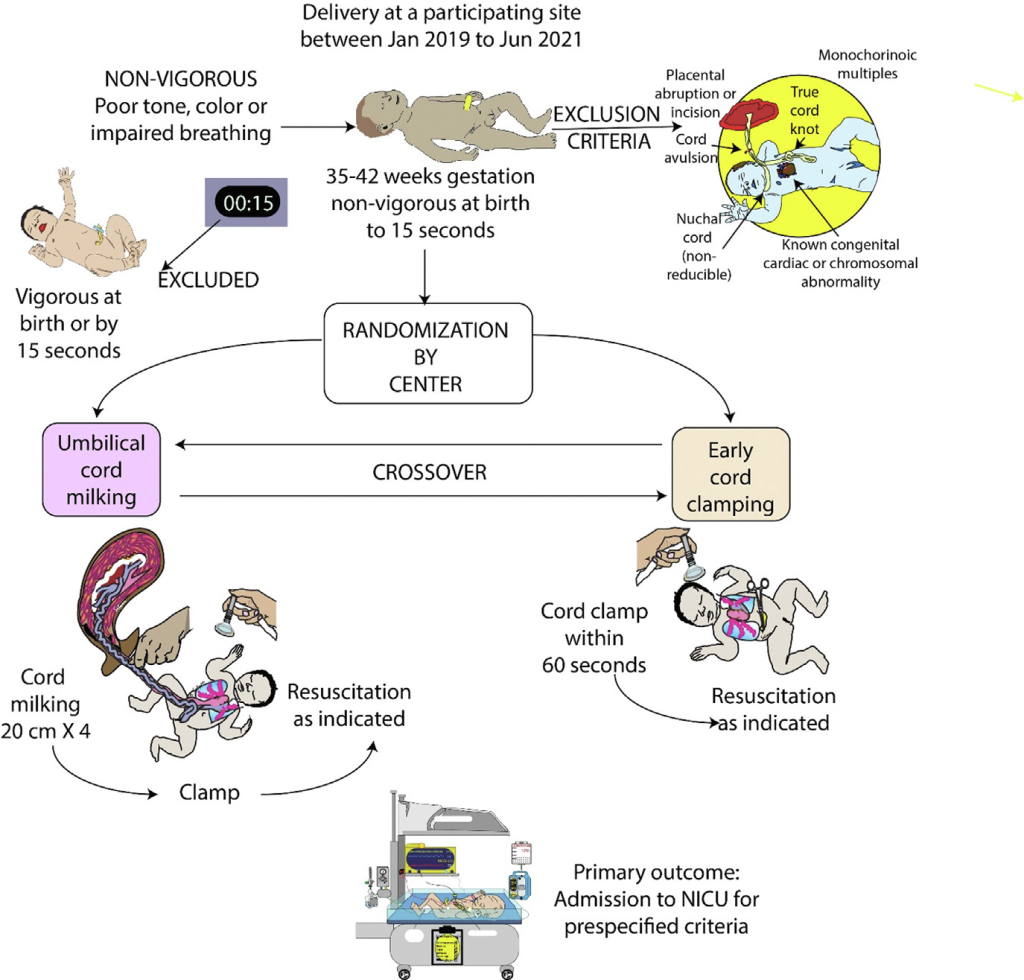

As usual, Anup Katheria is ahead of the game, and he has just published a reanalysis of the MINVI trial. This was a cluster randomized trial of cord-milking in term and near-term babies who were non-vigorous at 15 seconds of life. A cartoon of the protocol, from the original publication (Katheria AC, et al. Umbilical cord milking in non-vigorous infants: A cluster-randomized crossover trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022) is reproduced below.

The primary outcome of the MINVI trial was NICU admission for any of the following reasons “respiratory distress (tachypnea, grunting, or retractions), bradycardia or tachycardia, hypotonia, lethargy or difficulty arousing, hypertonia or irritability, poor feeding or emesis, hypoglycemia, oxygen desaturations or cyanosis, need for oxygen, apnea, seizures or seizure-like activity, hyperbilirubinemia, and/or temperature instability”. Although there were some apparent benefits of cord milking in the results, the primary outcome was 23% (cord milking) vs 28% (early cord clamping) and considered not ‘statistically significant’. Many of the individual reasons for NICU admission were slightly lower in the cord milking group.

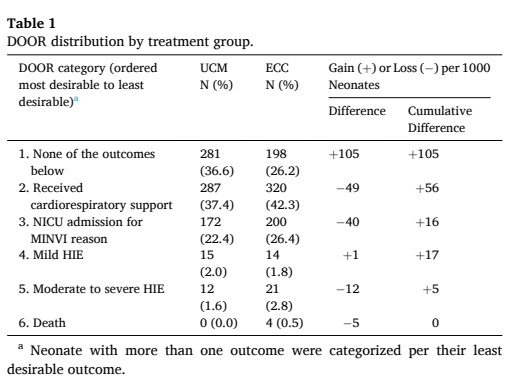

This reanalysis (Katheria AC, et al. Application of desirability of outcome ranking to the milking in non-vigorous infants trial. Early Hum Dev. 2024;189:105928) used a DOOR approach. Which depends on a list of ranked outcomes which are shown below in the first column of the table; the table also shows the numbers and proportion of babies in each of the two groups, Umbilical Cord Milking (UCM) and Early Cord Clamping (ECC) who have that outcome as their worst outcome.

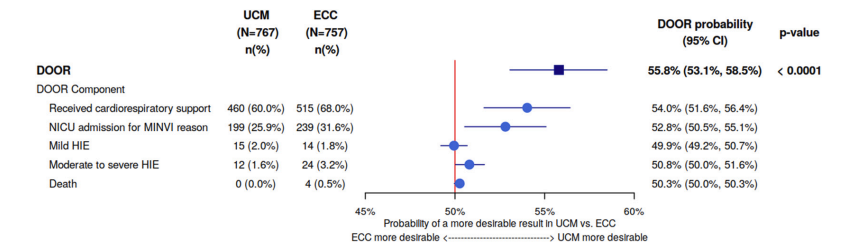

The DOOR analysis entails a calculation of how likely it is that a member of the UCM group will have a better outcome than a member of the ECC group. If the interventions are equivalent, then the possibility will be 50%, 95% confidence intervals can be calculated, and if they do not include 50%, then you can conclude, with 95% confidence, that the results are different. You can see in the figure below that the overall DOOR ranking was more likely to favour ECM, with the percentage of the comparisons between UCM and ECC babies favouring UCM being 56%, with 95% CI of 53 to 59%, and each component of the score favouring UCM, except for mild HIE being equivalent.

The last author of this new paper with Anup Katheria has been heavily involved in developing this approach in infections disease research, and they have an extra twist in those studies, that, if there is a tie in outcomes, you can take into account the duration of antibiotic use. Getting an equally good clinical outcome with a shorter course of antibiotics is considered an advantage. I think they mostly invented this wrinkle for the cute acronym RADAR (Response Adjusted for the Duration of Antibiotic Risk) Evans SR, et al. Desirability of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) and Response Adjusted for Duration of Antibiotic Risk (RADAR). Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):800-6. I’m not sure how this could be adapted to our population, but I like the idea that if you get equally good outcomes with less intervention, that is a good thing.

I know there are other groups that are already considering this approach, which I think could be easily adapted to be a much better primary outcome variable for clinical trials in neonatology. It clarifies the difference in outcomes between groups, giving greater weight to worse outcomes. How to develop the prioritised list of outcomes, and what order to place them in, should definitely be done in collaboration with parents.

Thanks Keith. This is time we use more of the DOOR approach to neonatal trials- thanks for educating us.

Mohan