A trial that has been awaited for a while has just been published (Watterberg KL, et al. Hydrocortisone to Improve Survival without Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(12):1121-31). It was a multi-centre RCT of hydrocortisone in 800 very preterm babies at elevated risk of developing chronic lung disease. Eligibility criteria were a GA at birth of <30 weeks, being intubated for more than 7 days, and still receiving invasive assisted ventilation at 14 to 28 days postnatal age. They had not previously received steroids for lung disease (it seems that a short prior course of steroids for other indications was acceptable according to the protocol, but many exclusions were of babies who had previous short course steroids). The study was performed with 2 primary outcomes, a short term outcome of “BPD or death”, BPD being defined as “moderate or severe BPD”, that is, needing oxygen or positive pressure ventilatory assistance at 36 weeks PostMenstrual Age.

The long term primary outcome was “NDI or death” NDI being a BayleyIII cognitive or motor composite <85, cerebral palsy with a GMFCS of >1, blindness or deafness.

The intervention was hydrocortisone at a starting dose of 4 mg/kg/day (iv or enterally) and weaned over a total of 10 days or placebo. The intervention also included the possible use of open-label dexamethasone (DEXA), in either group, at least 4 days after the hydrocortisone was stopped.

The relevant section of the protocol reads as follows : Infants who remain successfully extubated are not to be treated with open-label glucocorticoids as therapy for BPD. This will be a protocol violation. (ii) Infants who are not extubated during the study treatment period or who are subsequently re-intubated may be treated with open-label dexamethasone after ≥ 4 days following the last dose of study drug. Open-label dexamethasone will be encouraged to be prescribed as described by Doyle.

Forty per cent in each group received DEXA. Those who received DEXA got a median of 10 days treatment. There were another 15% of babies who received non-study systemic steroids (presumably mostly DEXA) during the “14 day study period”, that is, the 10 days of hydrocortisone and the 4 days delay before DEXA was allowed by protocol, therefore they were protocol violations; the proportion was similar in the 2 groups, 14% of the hydrocortisone group, 16% placebo. Its not clear how many of the protocol violation babies also received open-label DEXA by protocol, and there is likely to be some overlap, but probably around 50% or more of each group received a course of DEXA.

At 36 weeks there was a small survival advantage to the hydrocortisone group (mortality 4.8% compared to 7% in controls) but this difference was even smaller by discharge (8.8% vs 10%).

The babies in the hydrocortisone group were more likely to be extubated during that 14 day study period, but, as you can see from the overall results above, this did not lead to a lower proportion of babies with “moderate to severe” BPD.

I put the “moderate to severe” in quotations as, of course, this is what in the past was just referred to BPD. Is this the outcome we should be focusing on, in large important trials like this?

There is little correlation between having a 36 week diagnosis of BPD and longer term respiratory problems, in one study from the CNN and CNFUN (Isayama T, et al. Revisiting the Definition of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Effect of Changing Panoply of Respiratory Support for Preterm Neonates. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(3):271-9), only 10% of babies with this as a diagnosis had “serious respiratory morbidity” after discharge, which was defined as “either (1) 3 or more rehospitalizations after NICU discharge owing to respiratory problems (infectious or noninfectious); (2) having a tracheostomy; (3) using respiratory monitoring or support devices at home such as an apnea monitor or pulse oximeter; and (4) being on home oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure at the time of assessment between 18 and 21 months corrected age.” That does seem like fairly serious respiratory morbidity, and having oxygen or respiratory support at 40 weeks led to 16% of the babies having this outcome, rather than 10% at 36 weeks. The 3 or more hospitalisations was used in this definition based on it being the 95th percentile, which I think is not the best way to define “adverse respiratory outcome”, wouldn’t it be better to ask parents what they think is an adverse respiratory outcome, and use that to determine how much impact postdischarge respiratory morbidity has on a family?

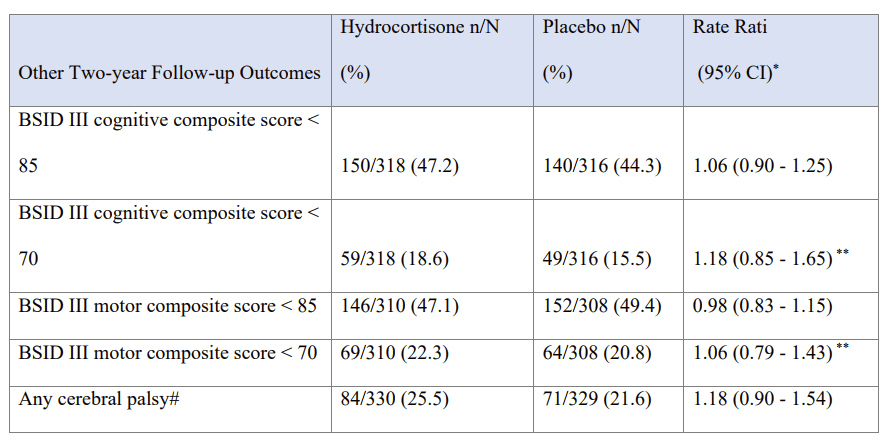

To return to the new trial publication, the neurological and developmental outcomes at 2 years corrected age were very similar between the groups, the supplementary data file has this table:

In other words, slightly better cognitive outcomes with hydrocortisone, slightly better motor outcomes with placebo, but no convincing difference in either, and all compatible with random variability.

The average GA of the babies was just under 25 weeks, and the stratum of babies 22 to 26 weeks GA had a similar primary outcome (i.e. no real difference) to the more mature babies. The mean oxygen requirement at enrolment was 50%, even though there was no minimum FiO2 requirement for eligibility. The high mean FiO2 at enrolment suggests to me that those babies who were considered close to extubation, perhaps on low settings and close to 21% oxygen, may not have been enrolled.

The study is therefore a comparison of hydrocortisone with backup dexamethasone, to placebo with backup dexamethasone, in a very high risk group of babies. It would be interesting to see the long term outcomes of babies who did not receive dexamethasone in the two groups, such a comparison might help to reassure that hydrocortisone used like this is safe. As it is, the very frequent treatment with DEXA in both groups may have diminished the ability to find a long term negative (or positive) impact of hydrocortisone, as well as dramatically diluting any potential advantage of hydrocortisone on lung injury.

Comparing this trial to the previous trial which is the most similar, STOP-BPD, in that trial the steroid dose was slightly higher to start with (5 mg/kg) and continued for twice as long (22 days total),was started earlier (7 to 14 days), and had more restrictive entry criteria (respiratory index by the end of the study (MAP x FiO2) >2.5). You will remember that the entry criteria were modified during the performance of that trial, as many babies who had a respiratory index which was not high enough to satisfy the initial entry criterion (>4.5) were being treated with hydrocortisone outside of the trial. 2.5 means 25% oxygen with a mean airway pressure of 10, for example. But in fact the babies were not as sick as those in the new trial, the average respiratory index at enrolment was around 4, in the new NICHD trial it was over 5.5. (The methods of calculation are slightly different, either using FiO2 as a fraction or as a percentage, so just multiply or divide by a hundred).

In STOP-BPD, rescue steroid use was with open-label hydrocortisone, rather than with DEXA, and was also very frequent, but, in contrast to the new trial, there was a big difference in rescue steroid use between groups, 28% in the active treatment group, 57% in the placebo group.

That study also had neurodevelopmental follow up at 2 years corrected age. The trends all were in favour of the hydrocortisone group, with both BayleyIII cognitive and motor scores slightly favouring the hydrocortisone group. Unfortunately this was only published as a research letter in JAMA (Halbmeijer NM, et al. Effect of Systemic Hydrocortisone Initiated 7 to 14 Days After Birth in Ventilated Preterm Infants on Mortality and Neurodevelopment at 2 Years’ Corrected Age: Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(4):355-7), so it is a short publication, without much detail, and there is no additional analysis of the babies according to treatment actually received.

These results were obtained with over 100 of the placebo babies having received hydrocortisone, so again, it is not clear if the hydrocortisone was harmful to long term outcomes or not. With so much cross over, it would be very difficult to ascertain in any case, as the sickest babies will have received non protocol steroids, so they are likely to have poorer long term outcomes. But at least in this trial the additional, non protocol steroids appear to have been mostly hydrocortisone, so it might be possible to determine, for example, whether there was a dose-response for developmental outcomes.

What does this all mean for steroid use in preterm babies with evolving BPD?…. part 2 coming soon!