As we approach world NEC awareness day (May 17th) I thought I’d do a quick PubMed search to see if I’ve missed anything recently, so I started typing “necrotizing” in the search bar, which immediately suggested “necrotizing enterocolitis” as one of the possible completions, so I clicked on that and found there were 9,700 potential hits, ranging from the first reports in premature infants in the 1950’s, the first US series in 1964, and a progressive increase in annual publications to 766 last year. Apart from the odd report in animals or older patients, almost all of these publications are about neonatal human NEC, or animal models of neonatal NEC.

Recent work that caught my eye included the following, a study of the intestinal “virome” in very preterm babies. This was an “-ome” that I hadn’t come across before, but it was fairly obvious what it meant. (Kaelin EA, et al. Longitudinal gut virome analysis identifies specific viral signatures that precede necrotizing enterocolitis onset in preterm infants. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(5):653-62) The authors identified a number of bacteriophages and what they call “eukaryotic viruses” which stumped me for a minute, as I was stunned that a virus could be a eukaryote; but of course a virus cannot be a eukaryote, the term refers to viruses which infect eukaryotic cells. Such as COVID, or all of the other viruses causing disease in humans. Not too surprisingly, the large majority of viral signatures that they found in the stools of preterm infants were unclassifiable. To be really honest, I don’t understand a lot of the analyses that they performed comparing the sequential viral and bacterial microbiomes of 9 preterm babies who developed NEC and 14, matched for GA and birth weight who did not. So, unusually for me, I will have to take them at their word that they found that “the viromes of infants who developed NEC converged towards a reduced level of beta diversity before NEC ensued and this convergence was characterized by specific viral signatures”. Of course this is a small series form a single hospital, and will need to be confirmed, but it suggests that viruses may have a role in the development of NEC, and specifically some bacteriophages may be implicated.

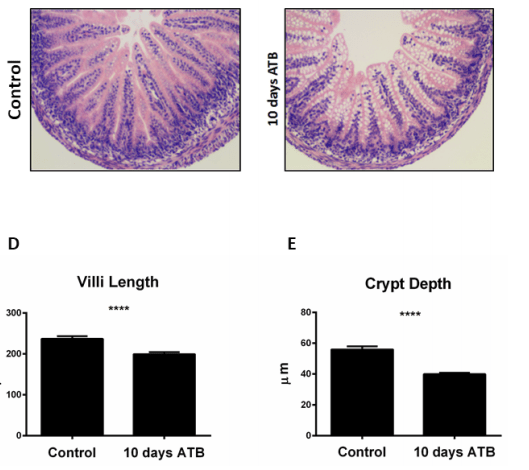

Other evidence that examines how we mess up the microbiome having a significant impact on NEC comes from studies like this one in neonatal mice (Chaaban H, et al. Early Antibiotic Exposure Alters Intestinal Development and Increases Susceptibility to Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Mechanistic Study. Microorganisms. 2022;10(3)) half of whom were randomized to receive antibiotics (amp and gent) for 10 days. 4 days later they all received oral Klebsiella pneumoniae or an oral vehicle. Just getting antibiotics for 10 days severely impacted on gut development with fairly dramatic effects on villi length and crypt depth.

Goblet cells and Paneth cells were also impacted, as were intestinal permeability which was dramatically increased, and the antibiotics, not surprisingly, had major effects on the intestinal microbiome. When they got both antibiotics and then later Klebsiella, intestinal permeability was even further increased, TNF alpha and IL-1 beta also shot up, and half of the animals developed an intestinal injury which looks a lot like NEC.

Another fascinating study looks at whether using AI to interpret intestinal microbiome composition could possibly predict NEC (Lin YC, et al. Interpretable prediction of necrotizing enterocolitis from machine learning analysis of premature infant stool microbiota. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022;23(1):104), again I can’t pretend to understand a lot of what they did, but by re-analysing data from 2 prior cohorts of sequential microbiome analysis in preterm babies, among whom a number developed NEC, they were able to train an AI system to predict NEC. The system predicted NEC in the majority of preterm babies at birth, which isn’t very useful, but you could just ignore the first couple of days, and then as the days progressed there was a progressive divergence leading eventually to a reasonably good sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 90% for predicting NEC, which was possible 8 days prior to clinical presentation. This hold out hope that sequential microbiome analysis could eventually prospectively be fed into the machine learning algorithm and give you a weeks notice that a baby is going to get NEC. What you would do about it at that point I have no idea, but maybe you should block the toll-like receptor-4.

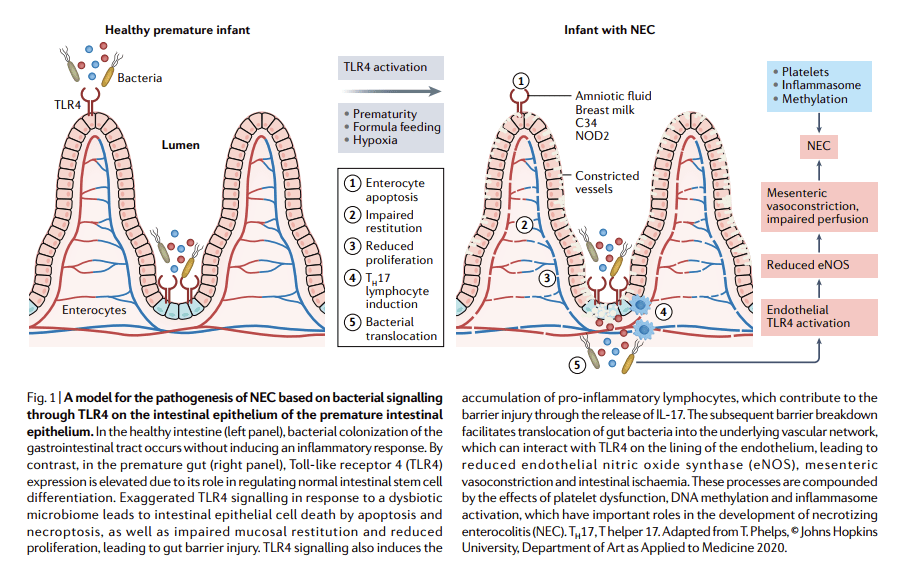

There are couple of recent reviews which discuss the pathogenesis of NEC, this one (Hackam DJ, Sodhi CP. Bench to bedside – new insights into the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022. ) concentrates on the role of the TLR4, in the text it is surprisingly dismissive of the importance of microbiome disturbance, which I find difficult to understand. I think it is clear that B infantis interacts with TLR4 and exerts anti-inflammatory effects as a result.

Improving gut colonisation with B infantis, and/or other organisms that reduce inflammation by interacting with TLR4, as well as potentially other mechanisms will probably reduce NEC incidence.

Speaking of which there is a new Cochrane review of synbiotics for the prevention of NEC which found 6 trials. Unfortunately 3 of them used inulin as the prebiotic part of the “syn-“, which is quite probably not the best prebiotic to consider, other oligosaccharides and in particular lacto-N-tetraose, are much more effective at promoting the growth of B infantis. The 3 small trials which used other oligosaccharides were of variable quality, and give no real confidence that the reduction in NEC that they showed is a reliable effect. Ongoing work confirms the probable importance of lacto-N-tetraose, such as this one (Wu RY, et al. Structure-Function Relationships of Human Milk Oligosaccharides on the Intestinal Epithelial Transcriptome in Caco-2 Cells and a Murine Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2022;66(4):e2100893.) which showed that mice which received one of 3 different human milk oligosaccharides were protected against NEC which occurred in the controls, induced by hypoxia, hyperosmolar feeds and lipopolysaccharide; but that the mechanisms of protection were different between the oligosaccharides. Lacto-N-tetraose appears to have been one of the most effective at reducing inflammation.

There is still so much to learn about this disease, and despite the many advances in neonatology over the years, progress in NEC has been slow; although probiotics reduce the incidence of NEC it still occurs, and still devastates some infants. Determining which probiotic is most effective, how to enhance efficacy with the most effective prebiotic/HMO, and what to do when early signs of NEC or of intestinal dysbiosis occur, are topics that require further investigation.