To me, this new ‘clinical report’ was a major disappointment.

Even though there are some good parts to this statement, there is one huge, major failing: there is absolutely no evidence that parents were consulted or included in the process of statement development. In 2015 how can you possibly release a clinical practice guideline like this and not involve families?

As for the substance of the ‘clinical report’ there is good along with the less good.

First the good, the report goes into some detail about the limitations of gestational age assessment, and the limitations of gestational age as a prognostic factor. The discussion of these limitations is quite well done in general.

There is also a clear statement that decision making based on clinical evaluation in the delivery room is inappropriate.

It is recommended, therefore, that decisions regarding resuscitation be well communicated and agreed on before the birth, if possible, and not be conditional on the newborn infant’s appearance at birth.

There is also a discussion around communication skills, and the importance of parental values. However, even this part was written, it appears, without any parental contribution.

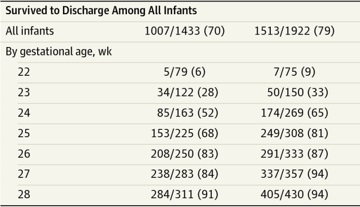

Also despite these parts which I think are valuable, there is still a statement that under 22 weeks infants are not viable, and resuscitation should be offered for infants born at or later than 25 weeks of gestation. I think that this statement largely destroys what they discuss elsewhere about the limitations of gestational age thresholds. Some babies at 25 weeks have much worse predicted outcomes than other babies born at 24 weeks. Putting this arbitrary limit goes directly against what they have just discussed in the rest of the document. It leaves us with the irrational situation that a baby with a good predicted outcome at 24 weeks and 6 days is considered “optional”, but an infant one day further on, even if smaller and with other serious negative risk factors, is considered a mandatory resuscitation.

Within the document another big problem is the use of terms which are not defined. Terms which are vitally important to the discussion such as:

futile

long term neurologic impairment

severe long term neurologic impairment

intact survival

neurodevelopmental impairment

severe neurodevelopmental impairment

significant long-term neurodevelopmental morbidity

There are also phrases which are written in a way that shows a negative bias, with a selective quoting of the literature, and often inaccurately quoted references. These problems sometimes occur all together:

… the fact that most surviving preterm infants born before 25 weeks’ gestation will have some degree of neurodevelopmental impairment and possibly long-term problems involving other organ systems. Infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation have reported rates of moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment of 85% to 90%; for infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, these rates are not significantly lower. The risk of permanent, severe neurodevelopmental and other special health care needs affect both the infant and the family and, for some parents, may outweigh the benefit of survival alone.

If you don’t define neurodevelopmental impairment, then that first phrase is meaningless (even if you want to call it a “fact”). The reference they use (which is here) for that first phrase, is a review article which does not, as far as I can see, include any such statement, and, in fact I am not sure of any data set that would confirm that “fact”. Many cohorts show very different results. As one example, the EXPRESS study has reported outcomes to 2.5 years of babies in the 22 to 24 week GA group for a national cohort. Of the 138 babies between 22 and 24 weeks there were 59 that had “any neurodevelopmental impairment”, the others being defined as being without impairment. I don’t think that qualifies as “most have some degree” of impairment. A more unbiased and accurate evaluation would be that “most surviving preterm infants born before 25 weeks have no impairment”, and “those that are impaired usually have mild or moderate impairment”.

Another phrase which I think is biased is this, from that section above, “…infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, these rates are not significantly lower [than the infants born at 22 weeks]”, why not put that the other way around? You could equally well say that “…infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, these rates are not significantly higher” And if you actually look at the data that the outcomes of 22 week infants is based on, the numbers are minuscule. The systematic review by Greg Moore and co-workers in Ottawa (which is one of the references for this report) found 12 such babies with outcomes analyzed after 4 years of age; 31% of those 12 babies were severely impaired (and 43% moderately to severely impaired), which was not significantly different to the 17% (of 73 babies) at 23 weeks.

In other words the majority of the very small numbers of survivors are not seriously impaired. Which comes back to the lack of definitions, “severe long-term neurologic impairment” in many studies could, for example, mean a hemi-paresis. Most infants with hemi-paresis, and their families, would not, I bet, consider that their life was intolerable. Shouldn’t we be asking them?

Don’t we need to have a discussion about what impairments are sufficiently severe to consider withholding intensive care interventions? Don’t we need to have that discussion with parents and with other lay people?

Saroj Saigal has done so for one cohort of patients from her practice. Some of her work is referred to in this report. In her work, only one parent thought that their ELBW child (now adolescent) had a quality of life that was worse than death. All the others reported a positive quality of life, and overall there were only minor differences compared to offspring who had been born at term.

(There are several other references used in this statement that don’t say what the authors state. For example the “clinical report” states “In addition, attitudes may be changing; whereas earlier studies suggested that obstetricians and neonatologists tended to overestimate morbidity and mortality rates for extremely preterm infants, that no longer seems to be the case.7,8” Neither of those 2 references for “no longer seems to be the case” address that issue, there is no report in either publication of obstetric or neonatal estimates of morbidity and mortality. Both are reports of how those specialists practice; they show, for example, that many obstetricians in New York state do not know their local definitions of a live birth. That study asked respondents at what gestation or weight they considered a fetus viable, the other study reports what obstetricians and neonatologists said that they include in their usual antenatal counselling practice. Both are interesting, but neither reports the estimates of morbidity or mortality of extremely preterm infants.)

A trial of therapy?

One thing that I think is also missing is a discussion of the idea of a “trial of therapy”. The decision-making is presented in this clinical report as a dichotomy between full-blown intensive care, on the one hand, and palliative care on the other. But Bill Meadow, among others, has persuasively argued that the best time (in terms of accuracy of prognosis) to make a decision is rarely before birth, but rather afterward. Meadow W, et al. The value of a trial of therapy – football as a ‘proof-of-concept’. Acta Paediatrica. 2011;100(2):167-9. Not only does accuracy improve, but many parents find a moral value in at least trying to have a good outcome from a terrible situation. For extremely high-risk infants, that should at least be a part of the discussion. In my own practice for a couple of recent cases of extremely high risk patients (not preterms, but with very serious malformations) it was decided, with the parents, that the best approach would be to institute active intensive care, but if the pulmonary hypertension was too bad, or the associated malformations too severe, then we could limit the extent and duration of life-sustaining interventions. I don’t see why that kind of approach should not be a important option when discussing extreme prematurity, and indeed in our practice it often is.