It was fairly recently that I deconstructed a truly terrible database analysis which claimed that neonatal mortality was dramatically increased among very preterm infants who received mother’s own milk (MoM) and donor human milk (DHM), without any formula or fortifier, compared to a group which only received MoM and artificial formula. Almost certainly, this was because many of the deaths in the MoM+DHM group occurred before the babies had survived long enough to receive fortification. A baby who survived for a few weeks and then received some fortification or formula being deleted from the group, even if the change of diet occurred after the primary outcome (surgical NEC) had been determined! The study also claimed that MoM+DHM was associated with more surgical NEC (3.5%) than MoM+formula (1.7%), but with a difference much smaller than the enormous difference in mortality. This could well be another example of confounding by indication, and again, much of the feeding data were derived from medical record abstraction which included many days, or weeks, after the occurrence of the NEC, up to and including the day of discharge.

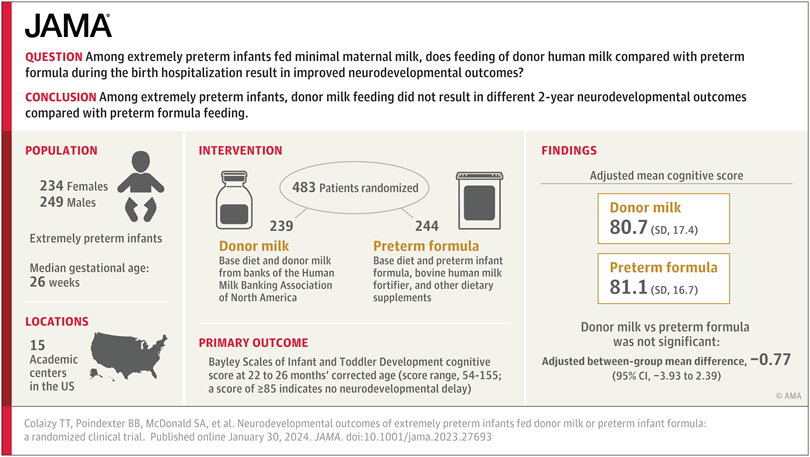

My letter to the editor about this has now been published. One thing I mentioned in my discussions of the data about DHM was the MILK trial, for which I included data from Clinicaltrials.org, and which has now been published. (Colaizy TT, et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants Fed Donor Milk or Preterm Infant Formula. JAMA. 2024).

The details of the protocol are now available, with the full publication. Eligibility included a GA <29 weeks or birth weight <1000g, 483 babies were randomized. If the mother never initiated breast milk expression, or stopped before 21 days of age, or produced “minimal” amounts of MoM, then the infant could be included, and randomized, which could therefore occur any time between birth and 21 days of age. The median age of randomization was 16 days, and the median age of starting oral feeds was 4 days. Which makes me wonder why, on average, these babies were not fed for 4 days? I think most babies, of any gestational age, can be fed on day 1. Our protocol is to only withhold feeds for babies in shock and/or on inotrope/vasopressors, which is a small minority, most extremely preterm babies receiving either MoM, or if not yet available, DHM, within 24 hours.

The eligibility up to 21 days dilutes the potential differences between groups, I suggest, as many babies will have had some MoM, or DHM, or formula, before they were enrolled. Even after being enrolled, many babies in both groups received some maternal milk, which is reported as the number of weeks of any MoM, and averaged about 1.7 weeks.

I’m not sure how many babies were in those 3 slightly different subgroups (no MoM, mother stopped expressing before 21 days, and mother not able to produce enough milk), but some analyses were done for the subgroup who had zero MoM. In the supplemental materials, it looks like there were 369 babies in total that completed follow up, 79 of whom had zero MoM; in other words it is a minority of mothers who never expressed at all.

The primary outcome variable was the Cognitive Score on the Bayley version 3, performed at 2 years corrected age. Another thing which I find a bit weird, is that the babies who died were assigned a cognitive score of 54 (the minimum possible); it is one way of integrating the competing outcome of mortality with developmental outcomes, but, depending on the risk of death, it could well dilute any difference in cognitive outcomes, especially if there were an imbalance in mortality. It also makes the scores look a lot lower than they really were, mean scores being about 5 points higher when the non-survivors assigned scores were removed. Scores on the language composite (44) and motor composite (49) were also assigned for babies who did not survive.

In any case, all of the developmental and neurological outcomes were very similar between groups. In the supplemental material the analysis restricted to the survivors is given, which shows that all of the mean and median scores are slightly better in the DHM group, but none of the differences are large enough to really have any clinical significance (and none are “statistically significant”). Interestingly, the differences are all greater in the “sole diet” subgroup, the median scores on each subscale being 5 to 6 points higher with DHM than formula, but the numbers are, of course, much smaller, and remain within 95% CIs.

Assigning the lowest possible score to the non-survivors leads to some slightly strange findings, for example, the Bayley motor composite scores among survivors were slightly higher in the DHM group, but identical when the non-survivors are added as scoring 49; and there was actually more cerebral palsy (all grades) in the formula group, 20% vs 15%.

For the short term outcomes, the most striking difference is in NEC, which was twice as frequent, 9%, in the formula group than in the DHM group, 4.2%. You may want to argue that NEC is a somewhat subjective diagnosis, but, as I haven’t yet mentioned, this was a masked trial. The study group went to some lengths to maintain masking, with feeds prepared daily by study staff in amber tinted syringes, which were continued for 120 days maximum, or until 1 week before anticipated discharge.

Another interesting outcome is that length and head circumference increased very similarly in the 2 groups, but the weight gain was a little greater in the formula fed babies. Both groups “lost” percentiles of length, and gained a little in head circumference, being born with weight and length z-scores of about -1, and head circumference z-scores of -1.4. At discharge the DHM group weighed about 140 g less. The Fenton standards were used to create the z-scores.

The study confirms the safety of donor human milk, and the reduction in NEC compared to artificial formula. This is despite the limitations in the study design, which made the study feasible (only enrolling babies whose mothers decided to not provide breast milk would have enormously prolonged the trial), but potentially diminished any difference between groups.

A recent editorial in Pediatric Research raised some reasonable concerns about the commercialisation of human milk for preterm infants, but suggested, with no real evidence, that there are also concerns about harm from DHM. It misquotes O’Connor’s previous RCT of MoM-receiving babies who either received supplemental feeds with DHM or artificial formula, and which also showed only tiny differences in mean cognitive scores, of 92.9 with DHM vs 94.5 with formula. The spread of scores was wider in the DHM group, so a somewhat larger proportion had scores between 70 and 85 in the DHM group, but this was a post hoc secondary analysis. The editorial also suggests that the mortality morbidity index was worse in the DHM group, in fact the tiny difference 43% vs 40% in this composite outcome was far from being significant, the only clinical outcome that was different in that trial was a much higher rate of NEC (stage 2 or 3, 6.6% vs 1.7%) with formula than DHM.

The MILK trial therefore confirms the benefits of DHM as a replacement for inadequate or absent MoM, compared to formula. It shows that NEC is lower, and there are no adverse effects. With reasonable standardized nutritional practices weight gain may be slightly less with fortified DHM than with formula, but length gain and head growth are very similar. Developmental outcomes are also unaffected, or are perhaps a little better with DHM, and maybe with less CP.

Although many of us are uncomfortable with the commercial side of human milk trafficking, most human milk banks are non-profit, and/or government supported, and most donors are altruistic women who wish to help others, and are fortunate enough to have a surplus of this precious resource. Our own local bank, like many others, does not accept donations from mothers who are within the first month of breast feeding their own baby, in order to not impact adversely on breast feeding their own infant. There are many challenges to ensuring adequate DHM supply, standardizing and optimizing nutritional intakes, adjusting fortification to alter nutrient supply by when growth is suboptimal. The MILK trial results confirm that responding to those challenges is worth the effort.

Pingback: Improving human milk for preterm infants. | Neonatal Research