Towards the end of last year the Canadian Pediatric Society published a new ‘position statement’. These are official proclamations of the society, supposedly based on the best available evidence to guide practice, and which become de facto standards of care. This particular one ‘Counselling and management for anticipated extremely preterm birth’ presented an opportunity to update a 20 year old statement.

Unfortunately it is a failure. It promotes an unethical standard based on simplistic thresholds of intervention. I have been writing a response to this for a while, and following the commentary in the CMAJ by Dan and Beau Batton, which makes many of the same points, I thought I would share this, in various different sections; this is the first.

This series of posts are a very expanded version of a commentary that has been accepted for publication in ‘Paediatrics and Child Health’. That commentary was written by a large group of collaborators from around the world, but is only 1500 words long, to comply with the word limits. I have taken the ideas from that commentary and developed them here.

The CPS position statement makes the following recommendations:

- At 22 weeks’ GA, since survival is uncommon, a non-interventional approach is recommended with focus on comfort care. (Strong Recommendation)

- At 23, 24 or 25 weeks’ GA, counselling about outcomes and decision making around whether to institute active treatment should be individualized for each infant and family. (Strong Recommendation)

- At 23 and 24 weeks’ GA, active treatment is appropriate for some infants. (Weak Recommendation)

- Most infants of 25 weeks’ GA have improved survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes and active treatment is appropriate for these infants except when there are significant additional risk factors. (Weak Recommendation)

I will leave aside for the moment the ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ recommendation part of this, more on that later, (see part 2).

This post will address the first 4 of the many failings in these recommendations;

1. Gestational age is only known imprecisely.

2. there is no explanation on how these thresholds were picked,

3. gestational age is only one part of risk assessment for these babies, and

4. the values and wishes of the parents are not mentioned.

1. Firstly, we never know the gestational age, except after in vitro fertilization. Recommending precise thresholds for intervention based on a number that is very imprecise is ridiculous. At its best, ultrasound, performed at around 12 weeks, can be plus or minus 5 days, 95% of the time. How can you recommend changing from one recommendation to another at a precise day, when the true gestational age may be 5 days more or less? Surely we need to recognize this limitation, and counsel families according to a range of possibilities based on GA plus or minus 5 days, as well as on other factors which affect survival. If the ultrasound is performed between 14 and 18 weeks the accuracy is plus or minus 10 days, after 18 weeks ultrasound is completely unreliable for assignment of GA.

2. Nowhere in the discussion preceding the recommendations is there any rationale given for not intervening at 22 weeks, but considering intervention at 23 weeks. In other words, why not start considering intervention at 23 weeks and 3 days? Or why not at 24 weeks, 2 days and 17 hours? Surely it couldn’t be just because it is a nice round number? This position statement, and others like it, can be lethal. Making potentially lethal statements which are based on a nice round number that happens to coincide with our traditional division of time into 7-day periods is worse than irrational. What changes at 23 weeks, 0 days and 0 hours to make intervention optional, when it was not even an option previously? This is never explained.

When you combine these 2 problems, the situation become ever more ridiculous, a mother in threatened preterm labour who presents with a best-guess gestational age of 23 weeks and 4 days, if you have a good quality 10 weeks dating ultrasound, has a 95% lower probability limit of actually being 22 weeks and 6 days, and therefore supposedly not eligible for active intervention. The 95% upper probability limit of gestational age would be 24 weeks and 2 days, which according to this statement changes everything.

But it is the same mother, the same family, the same fetus.

3. Survival of infants who receive intensive care at a best-guess gestational age between 22 weeks and 0 days and 22 weeks and 6 days (plus or minus 5 days!), when considered as a group, varies from 10% to 34% in different places who are willing to give active perinatal care, and, obviously, it is 0% if they are not willing to do so.

But we aren’t treating a group of babies, we are, potentially, treating individuals, some of whom have very poor chances of survival, and other who have chances of survival which are very much better. If you take the data from the NICHD network, the chances of survival at 22 weeks vary by more than 20-fold depending on other factors such as sex, birth weight, and having received steroids. The NICHD calculator gives chances of survival of between less than 1 % to more than 20% for individual babies born at a ‘best-guess GA’ of 22 weeks. We also know that infants whose ‘best-guess GA’ at birth is nearer to 23 weeks are more likely to survive than babies just at or just after 22 weeks. To lump them all together, just because it is easy, is doing a major dis-service to their families. For some babies, under certain circumstances, active intervention before 23 weeks gestation is a reasonable option, and if consistent with the families values and their wishes it should be considered.

A blanket recommendation to never intervene before 23 weeks gestation ignores all of these other factors. (gestational age uncertainty, other good or adverse risk factors, parent’s values, extra days of gestation…)

At the other end of this period of gestation, the statement reads ‘Most infants of 25 weeks’ GA have improved survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes and active treatment is appropriate…’. (First of all this makes no grammatical sense, ‘Most have …improved’, what does that mean; compared to what?) But more importantly, some infants born at 25 weeks have very poor chances of survival, many others have excellent chances, a boy born at 25 weeks and 1 day (plus or minus 5 days) who is small for gestational age and hasn’t had a chance to get steroids has a much lower chance of survival than a baby of 25 weeks and 6 days (plus or minus 5 days) with higher than average birth weight who has had steroids. Lumping them together is senseless. Just as importantly the girl at 24 weeks and 3 days (plus or minus 5 days) who has had steroids and has a good birthweight also has a much better chance of survival and a much better outcome than the previously mentioned SGA infant without steroids. But she is on the wrong side of this nonsensical divide, so her life is considered optional.

There is so much overlap between the outcomes of infants born at ’24 weeks’ and those born at ’25 weeks’ that it is unhelpful to divide the infants up this way.

Counseling a mother with threatened extremely preterm delivery should start with a risk assessment which must take into account her probable gestational age (with its inherent uncertainty) the estimated fetal weight (with its even greater inherent uncertainty, see below) the place of birth, whether the mother has been administered steroids, and whether the baby is single or if it is a multiple gestation, and then explore her values and the family’s desires.

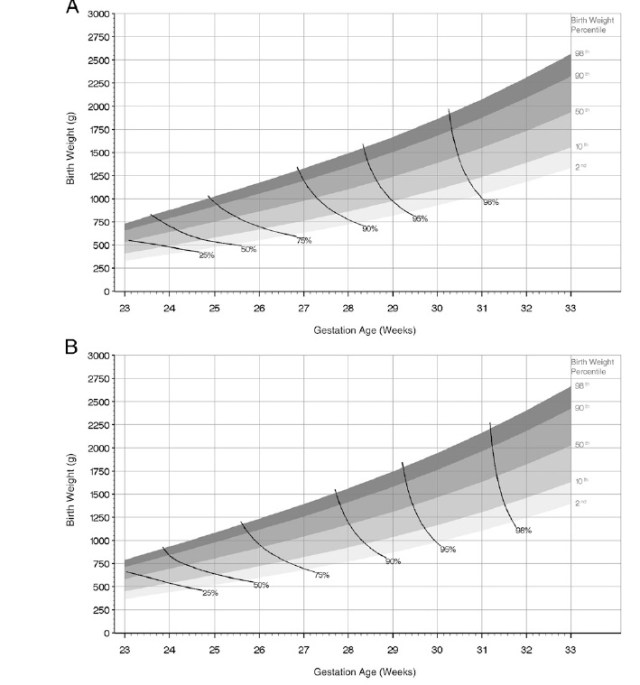

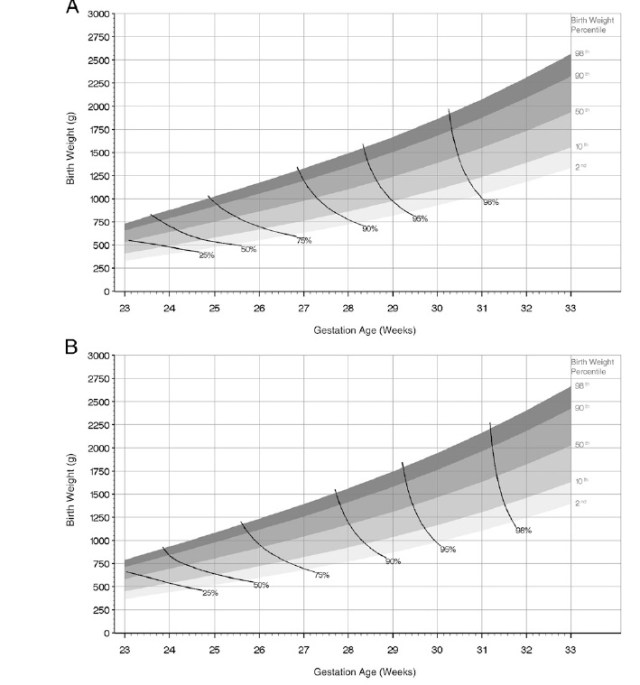

The graph below illustrates how little sense it makes to base decision making on gestational age. They are data from a fairly new study from the Trent region of the UK Manktelow B and others, recently released in Pediatrics.

The top panel is for girls, the bottom one for boys. The graphs show the different weight percentiles at increasing gestational ages, and the solid lines join combinations of weight and gestational age which have the same mortality. If a GA based guideline made sense then these lines would have to be close to vertical, and be the same for boys and girls. In fact they are closer to horizontal, the graphs would have to be multi- dimensional to also include the effects of having had steroids and being multiple or a singleton, but those factors also affect survival. In fact the near horizontal line at very low gestations means that birth weight has a closer relationship with mortality than does gestational age. Of course we don’t know the birth weight before delivery and estimated fetal weights can be helpful, as a sort of general guide, but estimated weights are much more variable even than gestational age, being plus or minus 10%, 75% of the time (depending on the study you use to do the calculations).

These are complex and difficult decisions in moments of stress. Reducing them to a simplistic mantra based on completed weeks of gestational age is unethical.

4. Finally the recommendations must mention the values and desires of the parents, which, although discussed in the text, are not in the recommendations, surely they are pivotal. Surely they must be mentioned in the recommendations.

I think that externally imposed arbitrary limits for resuscitation are unethical. In any field of medicine. In this particular case, threatened preterm delivery, the uncertainties of gestational age assessment and the poor correlation of gestational age with outcomes makes this triply unethical.