Here are my answers to 2 letters written regarding the article that Annie Janvier, Josianne Malo and I wrote about the impact of probiotics in our NICU.

I just realized that Elsevier’s rules allow me under the ‘permitted scholarly posting’ rules to post the text of my accepted publication (in this case my reply to the letters), as long as I don’t use the added formatting and so on of the final published article; and as long as I stretch it a bit and call this blog a website operated for scholarly purposes, also I have to include the following :

NOTICE: this is the author’s version of works that were accepted for publication in The Journal of Pediatrics. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to these works since they were submitted for publication. Definitive versions were subsequently published in The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;165(2):417-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.037 (I will add the reference for the second letter when it becomes available).

The first reply, which appeared on-line in May and in print in August, was in response to a letter from Oncel and others, in which they refer to their own studies which did not individually show a significant reduction in the incidence of NEC. Their letter can be accessed from here, and the references to their studies are given at the end of my response.

REPLY:

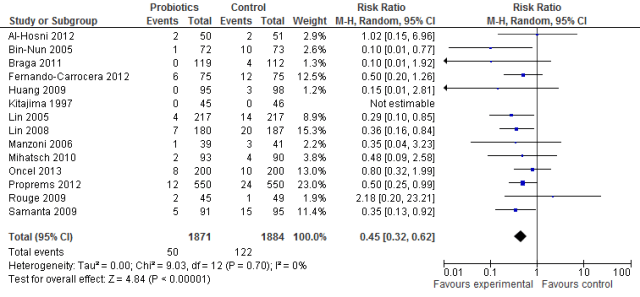

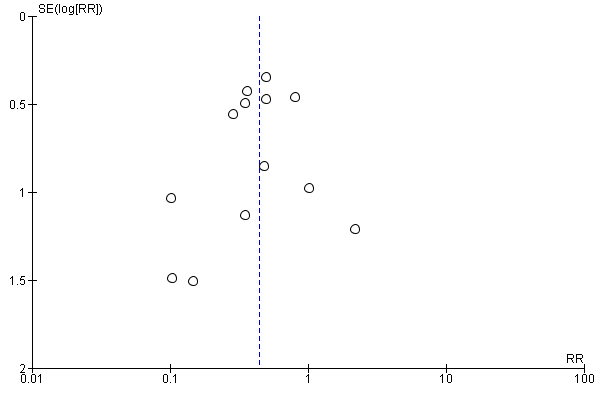

The efficacy of probiotics is no longer questionable. They are more firmly established than almost any other therapy in neonatology. It is true that there remain many questions, but none of those questions can be addressed by placebo-controlled trials. With respect to the studies produced from the authors’ own unit, I would submit that the results of the studies by Sari et al (1) and Oncel et al (2) are consistent with the published data regarding the efficacy of probiotics.

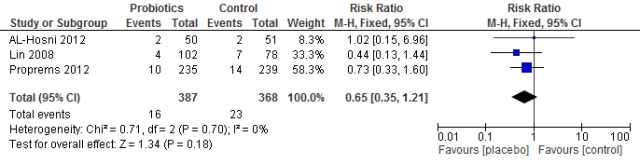

The study by Sari et al (1) showed a reduction in necrotising enterocolitis (stages 2 and 3) from 10 cases to 6 cases (of 110 in each arm of the trial) that is a 40% reduction with the use of Lactobacillus sporogenes. This result is consistent with the recent meta-analysis. Although that difference is not statistically significant, the very low rate of NEC in their unit makes the power of their study inadequate. They also showed a reduction in the combined outcome of death or NEC, from 13 cases to 9 cases.

The trial by Oncel et al (2) using L reuteri showed an extremely low rate of NEC in the control infants (5 cases among 200 enrollees), and a nonsignificant reduction in both NEC (to 4 cases) and death or NEC (from 13.5% to 10%).

I would concur with the authors that it appears that Saccharomyces are ineffective. This probiotic fungus may have some effect in reducing colonization with pathogenic fungi, but for the moment, any effect on NEC seems unlikely.

When there is already substantial evidence available, a Bayesian approach to new data should be taken. Such an approach shows that the 2 trials mentioned confirm other data. Clearly, if a very low background rate of NEC occurs without probiotics, the absolute benefit of their introduction will be smaller.

The data in those 2 studies also support the other major benefit of probiotics—improved gasrointestinal function. Both studies showed reductions in feeding intolerance with probiotics. Also, both studies support the safety of lactobacillus administration. The incidence of sepsis was almost identical between the 2 groups in the study by Sari et al, and was substantially lower in the probiotic group in the study by Oncel et al.

The studies by Oncel et al and Sari et al support the safety and efficacy of probiotics. Future studies comparing different preparations, doses, timing, and duration would be optimal. However, they will have to be very large to detect any clinically important differences. Probably large cluster randomized trials, using a neonatal intensive care unit as the cluster, will be the only economically viable way of answering these remaining questions.

References

1. F.N. Sari, E.A. Dizdar, S. Oguz, O. Erdeve, N. Uras, U. Dilmen. Oral probiotics: Lactobacillus sporogenes for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth weight infants: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr, 65 (2011), pp. 434–439

2. M.Y. Oncel, F.N. Sari, S. Arayici, N. Guzoglu, O. Erdeve, N. Uras, et al. Lactobacillus Reuteri for the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birthweight infants: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 99 (2014), pp. F110–F115

The second letter and the reply that Annie Janvier and I wrote will be published shortly, the letter accepts the scientific evidence for probiotics, but discusses, rather, concerns about safety. The authors were concerned about the regulatory status of probiotics in the USA which discourages companies from producing appropriate preparations. (I will add the appropriate links as they become available)

REPLY:

We certainly agree that it is essential when giving probiotics to preterm infants that we actually give probiotic organisms and not pathogens. Quality control of a product with well-characterized organisms and evidence that there are active probiotic organisms and no other contaminants present at the time of administration are required.

We agree with Drs Chan, Soltani and Hazlet that there is no doubt about the efficacy of probiotics for the prevention of NEC; the use of products identical to those used in the large multi-center RCTs, or other products with adequate evidence of their composition should therefore be considered mandatory. In fact there are sources of probiotics in North America that satisfy these conditions. The product (ABCDophilus) used in the Proprems trial(1) is manufactured by Solgar in New Jersey, a company with a good track record of quality control. The product which we used(2) has a Natural Product Number from Health Canada, which is evidence that the manufacturers follow GMP, that the strains are known and their DNA registered in the appropriate database, and that they are free of contamination with other organisms.

Another product used in several multicenter RCTs, Infloran, is also produced by a company with excellent quality control. The recent publication of the data from the German Neonatal Network(3) was from units that use Infloran for their infants. Infloran may be less readily available in the USA, but it certainly is available elsewhere.

There are products available in North America and elsewhere which could be used to protect preterm infants against NEC.

We agree that there is a need for a reconsideration of the regulatory status of these organisms, to enable manufacturers to supply safe, effective preparations, and to enable their use in the NICU. Many thousands of lives could be saved, and many hundreds of metres of intestine, not to mention the billions of neurones and the millions of dollars.

- Jacobs SE, Tobin JM, Opie GF, Donath S, Tabrizi SN, Pirotta M, et al. Probiotic effects on late-onset sepsis in very preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1055-62.

- Janvier A, Malo J, Barrington KJ. Cohort study of probiotics in a north american neonatal intensive care unit. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;164(5):980-5.

- Hartel C, Pagel J, Rupp J, Bendiks M, Guthmann F, Rieger-Fackeldey E, et al. Prophylactic Use of Lactobacillus acidophilus/Bifidobacterium infantis Probiotics and Outcome in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014(0).