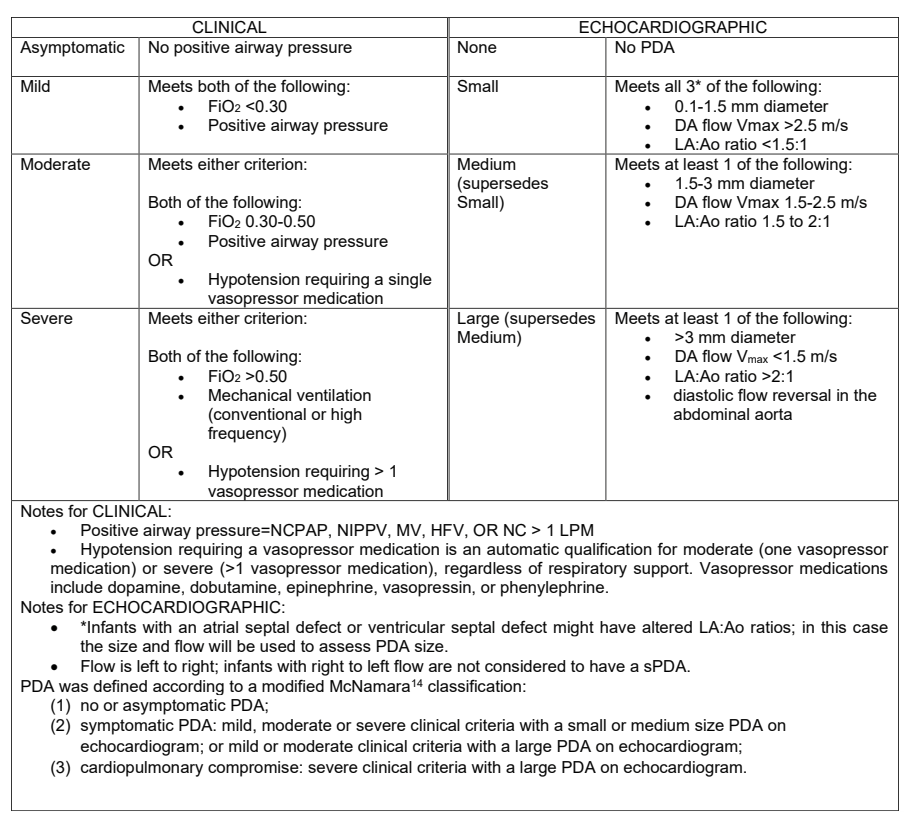

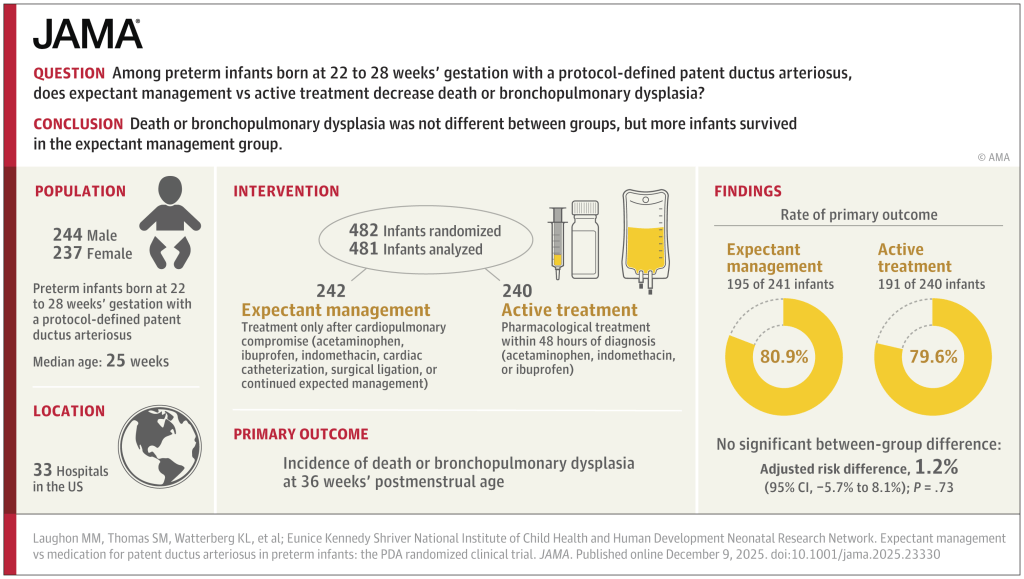

The latest large multicentre RCT has just been published. Laughon MM, et al. Expectant Management vs Medication for Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants. JAMA. 2025. In this trial, infants of 22 to 28 weeks GA were randomized at between 48 hours and 21 days of life after an echocardiogram. They were classified into: 1. no or asymptomatic PDA; 2.symptomatic PDA; or 3. cardiopulmonary compromise. Only group 2 were randomized. The definitions are shown below, including, at the bottom of the figure, the definition of group 2. Of note, infants receiving hydrocortisone were ineligible.

481 infants were randomized, within 48 hours of being eligible, and at a median of 10 days (IQR7-14) of age to either medical treatment, with ibuprofen, indomethacin or acetaminophen, or to control, expectant management. Controls were not supposed to receive any of those drugs unless they progressed to group 3 (cardiopulmonary compromise) or reached 36 weeks. There were unfortunately a large number of protocol violations, 60, or 25% of control, expectant management, infants received medical intervention (or surgical/catheter closure) for their PDA, of which 44 did not meet the agreed treatment criteria, and were therefore protocol violations.

I find this a little hard to understand, why get involved in the study if you are not prepared to abide by the protocol? Nearly 1 in 5 expectant group babies had PDA closure attempted even though they were not in the category of having severe clinical criteria with a large PDA, and therefore did not satisfy the protocol indications for treatment.

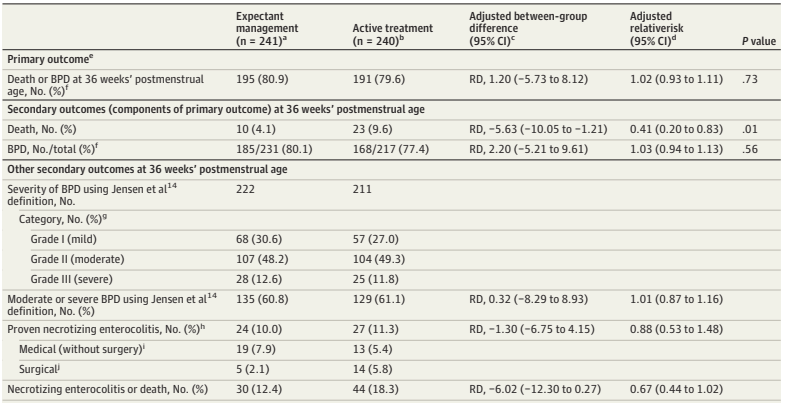

The primary outcome criterion was survival without BPD. I know, don’t get me started, designing a trial with a dichotomous outcome, that equates death with being in oxygen at 36 weeks, would be ridiculous in this day and age, in 2025, when so much better ways of designing trials with potentially conflicting outcomes, and analysing them in ways that take into account the relative importance of the outcomes, exist, and are now being used in other fields. It also leads to other rather, er, questionable decisions, such as defining death as death up to 36 weeks PMA. Really? Who cares about death up to 36 weeks, so an infant who dies at 37 weeks wasn’t counted in this trial?

The trial was, strictly speaking, a null trial. The primary outcome was identical between groups.

The breakdown of the primary outcome shows a lower mortality with expectant management than with intervention. At least, that is, mortality up to 36 weeks.

Surely the most important single question about any trial in sick preterm infants is : “If the baby receives treatment for the PDA, compared to expectant management, are they more likely to go home alive, or not?”

It takes a search of the supplemental materials, supplemental document 3, eTable 9, to find a partial answer to that question. The answer is that, by discharge or transfer, or 120 days after randomization (there were 18 infants still in the NICU at 120 days, and the investigators terminated the data collection), there were 14 deaths of the 241 expectant treatment infants. In the active treatment group there were 26 deaths among the 235 who actually got active treatment, there were 5 babies in this group who were not treated within 48 hours, and we don’t know if they survived or not.

If I do an ad hoc ITT chi-square, removing the unreported infants who had data collection truncated at 120 days, (as we don’t know if they lived or died) then the mortality is 14/237 vs 26/234. Or 5.9% vs 11.1%, a risk difference of 5.2% (95% CI of -0.2% to 11%), in other words not “statistically significant”.

As regular readers will know, I don’t think the arbitrary cutoff of p<0.05 is a good way to define what is real or not, which is why I almost always put “statistically significant” in quotation marks. But still, surely it was important to know that there were 7 pre-discharge deaths, at least, of the 40 total deaths, that occurred after 36 weeks. And there may have been more deaths after 120 days.

This has been a recurrent problem in similar studies, in BabyOscar for example, (Gupta et al 2024 in the figures below) mortality was reported at 36 weeks, and I can’t find any data anywhere about survival to discharge.

This is vitally important, the most recent meta-analyses show that medical treatment of the PDA increases BPD. Infants with severe BPD, still ventilated at 36 weeks have a measurable late mortality. Surely that is an outcome that we should know about?

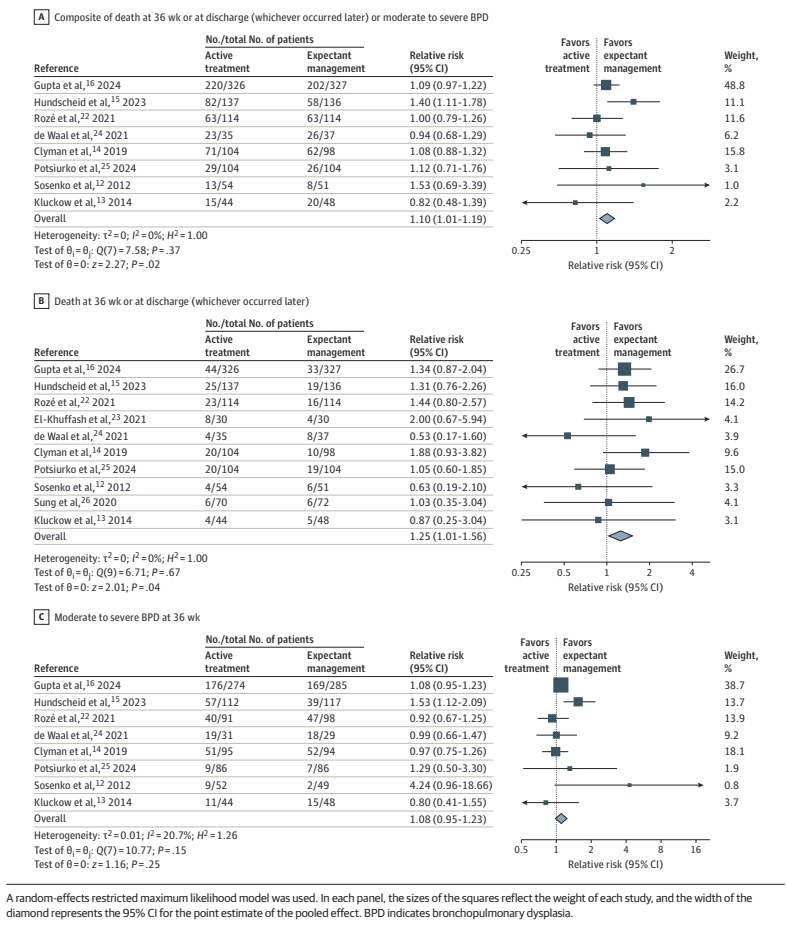

A recent SR/MA, published in May this year : Buvaneswarran S, et al. Active T “reatment vs Expectant Management of Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 179. United States2025. p. 877–85, included 10 trials of infants <33 weeks GA with “hemodynamically significant PDA (diagnosed by clinical or echocardiographic criteria)” who were randomized to active treatment compared to expectant management. There were a total of over 1000 babies per group and the primary outcome Forest plots are below

As you can see, this analysis suggests that there may well be an increase in “death at 36 weeks or at discharge (whichever occurred later)”, by which they actually mean whichever were the latest reported mortality figures.

They also include in the secondary outcomes, mortality before discharge, reported for less than half of the babies included in the various studies, which also shows an increase, but less marked, and with 95% CI including no difference.

To return to the new trial publication. I should make it clear that the trial was started in 2018, therefore probably designed in 2016 or so, and the authors are the brilliant Matt Laughon and the NICHD NRN centre representatives. The outcomes that they chose back then were the typical outcomes of PDA trials. It is easy for me, tapping away for my blog, to criticize, in retrospect, decisions that were taken a decade ago…

Nevertheless this trial, if you add it to the meta-analysis above, would surely confirm that closing a “haemodynamically significant” PDA does not appear to have any measurable benefits, and may well increase both mortality and oxygen requirements at 36 weeks, with most of the increase appearing to be in milder BPD, but probably a small increase in more severe disease also.

I am struggling to think of an evidence-based indication to close the PDA in a preterm infant. The data are, unfortunately rather muddy, there have been many protocol violations in the majority of the large trials. The exception was Hundscheid et al in the figure above, the BeNeDuctus trial, which only had 1 protocol violation in the expectant group. In BabyOscar, in contrast, 30% of the placebo group received open label medical or surgical PDA closure, about 1/3 of whom did not satisfy the protocol defined criteria. In the Rozé trial, 62% of the placebo babies had open label treatment, it is not clear how many satisfied their criteria for open-label treatment.

Which brings me to the question in the title, “Is there any indication for PDA closure?” The evidence-based answer to that question is that there are no criteria for defining a clinically important PDA, for which medical or surgical intervention has shown a survival benefit, or a reduction in lung injury.

I put it that way because there are some experts who continue to suggest that the big problem is with how we define a clinically important or “haemodynamically significant” PDA. (Bischoff AR, et al. Beyond diameter: redefining echocardiography criteria in trials of early PDA therapy. J Perinatol. 2025). And that all we have to do is better define the phenomenon. Which may be true, but requires that we prove it.

That recent opinion piece suggested that the criteria that should be used are those being tested in a pilot trial, the “Smart PDA” trial, which are not enormously different to the criteria used in the NICHD trial above. The authors of that piece remark that simply defining a significant PDA by diameter is insufficient; some PDAs with a large diameter have relatively modest impacts, and others of the same size may be associated with major shunts. The big difference between the Smart PDA trial, and the newly published NICHD RCT is that, in the newly published trial, being on CPAP, and having a PDA of over 1.5 mm would qualify for enrolment, without any other signs of a large shunt. In Smart PDA, you will also need at least one of the following signs of a L-R shunt

- Left atrium: aortic root ratio 1.5–2.0

- Transductal peak systolic velocity 1.5–2.0 m/s

- Left ventricular output (ml/kg/min) 200–400

- Diastolic flow pattern in the descending aorta: Absent/ retrograde

It seems to me that this has to be the next stage in the process, we should stop treating PDAs that do not have signs, such as those, of a substantial L-R shunt, doing so seems to have no benefit, and may well increase both oxygen requirements at 36 weeks, and perhaps even mortality. I think we have now reached the point where medical or surgical closure before 36 weeks PMA should only be attempted, in the context of an RCT, in infants with signs of a large shunt. There is currently no proven benefit to early PDA closure, and only harms.

In my recent practice I have seen some babies, usually “older” infants still ventilator dependent near term, with large shunts from a PDA, who have improved rapidly after ductal closure. In an NICU with 100 extremely preterm babies a year, there were maybe 3 or 4 in the last 4 years. It may be that those infants would have benefited from earlier closure, but in the absence of clearly defined criteria, which have been shown to predict benefit in preterm infants with a PDA, we frequently hesitate before performing a procedure with known risks. We have also had babies who have had little change in their clinical status after late PDA closure.

There do seem to be some babies who, anecdotally at least, seem to benefit from closure of the PDA. Our challenge as a community is to identify them, and hopefully to be able to identify them early enough that we can improve their outcomes.

well said Keith. Most of the babies with a « hsPDA » do not need treatment; but, clearly, there is a small subset of ELBW infants that do need PDA closure.

Keith: you bring out great points in king protocol violations and outcome measures that really do not reflect the effect of treatment vs no treatment. Also other confounding issues are not considered. Sad to see such trials in this day and age