I had thought this was a settled issue, Neil Finer showed many years ago that atropine alone decreased bradycardias during intubation. But as the authors of this new study point out, there is very little (or no) data about atropine as part of an intubation cocktail in the newborn. I have a bit of a beef with the introduction which suggests that the Kelly and Finer trial mentioned above was limited, as it did not “follow recommended premedication protocols”. But, when Neil Finer and Mark Kelly performed that study, there were no premedication protocols, and everyone in the world was intubating babies awake, and un-premedicated. Apart from this minor wording issue, the rationale for the study is reasonable. All the babies received fentanyl (1-2 microg/kg) and succinlycholine (2 mg/kg) premedication, and they were randomized to additional atropine (20 microg/kg) or placebo.

The primary outcome was a dichotomous, occurrence of severe bradycardia (<80 bpm for >10 seconds), there were 73 intubations with quite a large imbalance between the size of the groups, 49 placebo and 24 atropine. The randomization schedule was blocked, so I am not sure why there is such a big difference, which has an impact on the power of the study, compared to having 35 or so in each group. There was much more severe bradycardia among the controls, much more bradycardia <100, and much longer median duration of bradycardia, than among the atropine babies.

The premedication cocktail used is probably optimal, except for the dose of fentanyl; different doses of which have never been adequately compared. I am not sure that 1 microg/kg is adequate analgesia, my feeling is that larger doses, 2 to 5 microg/kg are needed for a procedure which is quite painful; but that feeling should be better investigated, and analysing pain in babies who have received a muscle relaxant is rather tricky! Alternatives to atropine, specifically glycopyrrolate, an analogue which has a greater safety profile as it doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, could well be preferable, but has not been adequately studied in the newborn.

Take Home Message: Premedication for neonatal endotracheal intubation should include atropine.

This is the type of study that would normally warrant an entire post on its own, but it has the misfortune to appear after the similar PLUSS trial.

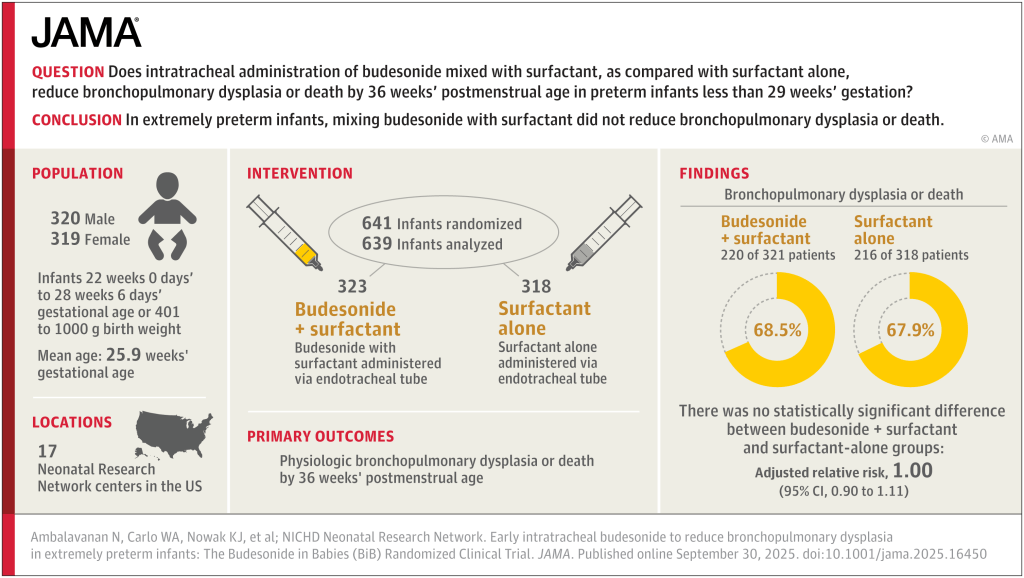

Differences to the PLUSS trial include that all the babies were intubated, there was no enrolment of babies receiving surfactant by LISA/MIST. In addition, all the babies were enrolled prior to their first dose of surfactant. They were all <29 weeks GA and <50 hours of age. They could receive a maximum of 2 doses, if they were retreated with surfactant <50 h of age.

Sample size was similar to PLUSS at 641 total, the initial plan was for 1160 infants, but the trial was stopped after around 50% for futility. In general, I think it is a mistake to stop for futility, but in this case, with the null results of PLUSS, which the investigators would have been aware of, the chances of finding important effects of budesonide became very unlikely.

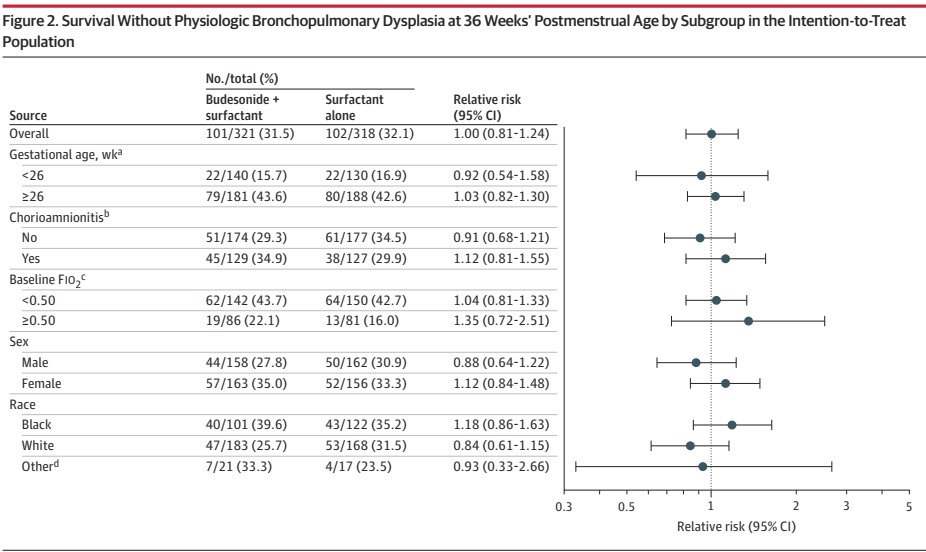

There was a tiny difference in mortality, 15% budesonide vs 13% placebo, and no differences in BPD, 63% of survivors per group. The combined outcome was therefore close to identical in the 2 groups. Unlike the secondary analyses of PLUSS, there was no difference in outcomes in any subgroup, including the subgroup of babies with more severe lung disease (>50% FiO2).

Other secondary outcomes were also similar between groups, there was a small shift in severity of BPD; there was no difference in severe BPD, but a slightly fewer moderate and more mild BPD in the budesonide group compared to placebo, but all the 95% CIs included no difference. I think this puts the nail in the coffin of routine budesonide supplementation in very preterm infants. We can’t overcome the adverse impacts of preterm birth and ventilatory support with exogenous steroid treatment.

Take Home Message : There is no rôle for routine addition of budesonide to early surfactant replacement.

Singh G, et al. Dopamine versus epinephrine for neonatal septic shock: an open labeled, randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol. 2025. This is a single centre trial among term and late preterm infants (>34 wk) with septic shock, it was registered 1st of March 2023, first patient enrolled the 6th of March, and enrolled 80 babies with fluid refractory septic shock, that is they continued to have signs of shock (defined in the publication) despite up to 60 mL/kg of fluid in term babies and up to 30 mL/kg in the preterm. Enrolment seems to have been completed in under 2 years, with 206 cases of septic shock, of whom 108 were “fluid-refractory”, 28 had exclusions and 80 were randomized. It is hard for me to imagine an NICU with over 100 cases a year of septic shock among term and near-term infants. The authors give no bacteriology, but the infants were diagnosed with pneumonia (60%), meningitis (30%) or “parenteral diarrhea” whatever that is (7%). Infants who received epinephrine were more likely to have reversal of their shock at 60 minutes (78% vs 63%), and more likely to have reversal of shock within 40 minutes (65% vs 43%). However, almost all the babies died, with no difference between groups (85% vs 88%).

Take Home Message : There are very few data on which to base choice of inotropes in newborns with septic shock. Clinical outcomes are poor, but there are some indications of better haemodynamics with epinephrine than dopamine.

Rochow N, et al. Individualized Target Fortification of Breast Milk with Protein, Carbohydrates, and Fat for Preterm Infants: Effect on Neurodevelopment. Nutrients. 2025;17(11). A couple of years ago, the group from McMaster published a randomized trial of individualized fortification of mother’s milk, compared to standard fortification, among VLBW babies and showed improved growth outcomes. Milk was analyzed 3 times a week, and fortification adjusted according to the results of that analysis. When I compare those older results with our local practice, they had rather poorer growth in their comparison, standard fortification group (mean 2.3 kg at 36 weeks), than we do, Lapointe M, et al. Preventing postnatal growth restriction in infants with birthweight less than 1300 g. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(2):e54–9, with an approach where we routinely target 165 mL/kg/day of milk fortified to 81 kcal/100mL. We rapidly increase volumes or fortification in case of poor growth, and the mean discharge weight, at a mean of 37.9 weeks, was 2.88 kg.

The advantage of the individualized fortification was greatest, as one might expect, in the subgroup of infants whose maternal breast milk had lower than average protein content. The babies with MoM protein content that was higher than the average had relatively modest impacts of the individualized approach.

Of course, our approach means that babies who need to have their fortification adjusted will have passed a period of poor growth, and babies may pass several days with inadequate protein or energy intakes. In contrast, the individualized approach could be considered more “prophylactic”, by adjusting fortification according to measured breast milk composition, one can ensure that recommended intakes are received throughout the hospitalisation, and hopefully avoid periods of poor growth. Or, at least, that would be the case if the intervention started early after birth, unfortunately in this study, the intervention started at an average of 24 days of life.

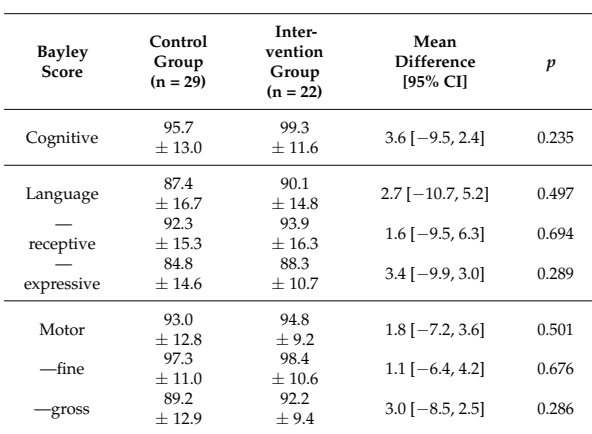

I have a lot of sympathy with the ideas behind the individualized fortification approach, based on the known variability of breast milk content, for women who deliver at term or preterm (for a very nice review see Gates A, et al. Review of Preterm Human-Milk Nutrient Composition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36(6):1163–72). But, it is time-consuming and costly, and needs some specialized equipment, i.e. an infra-red analyser for protein and fat, and a lab system for the lactose. Do the short term impacts translate to longer term outcomes? 69 of the original sample of 103 infants were examined at 18 months corrected age with neurologic examinations and Bayley version 3.

As you can see here, all the Bayley scores were a little higher in the intervention (individualized fortification) group. The differences were actually smaller between the low protein controls, and the low protein intervention infants. You can also see that there are only 51 babies with Bayley scores in this table, I don’t know where the results went for the other 18 babies, who, according to the CONSORT flow diagram, had their BSID evaluations. In a table a bit further on in the publication, which shows the proportions of infants below certain threshold scores of their BSID scores, the lost babies re-appear.

Take Home Message : These results suggest that individualized fortification might have some long term benefits, but that is not yet proven, there were at least no adverse impacts shown.

[like] Itani, Oussama [BSD] reacted to your message:

I do not conclude from Afifi et al that premedication should routinely include atropine: yes there was less severe bradycardia in the atropine group, but on the other hand there was more hypoxemia in the atropine group. Which variable matters more? We don’t have long term outcomes, and atropine could plausibly have negative impacts on hemodynamics – not to mention the ever-present risk of drug error.