This question has been puzzling me recently, as we are trying to evaluate our current approach, and whether it needs to be changed.

My bias has been that oxygen is toxic, and we should only give the minimum needed to maintain adequate saturation. But that, of course, begs the question “what is adequate saturation”? I take my approach partly from the results of BOOST, this was the trial with which Lisa Askie burst onto the scene of neonatal clinical research, (Askie LM, et al. Oxygen-saturation targets and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):959-67) with a multi-centre trial in 350-odd babies (<30 weeks GA) who were still needing oxygen at 32 weeks. They were randomized to have SpO2 targets of 91-94% or 95-98%. There were no advantages shown of higher saturations, but far more high sat group babies needed oxygen at home, 30% vs 17%, and more babies died of pulmonary causes (6 vs 1, p=NS).

The STOP-ROP trial was also cautionary. In that trial, very preterm infants with pre-threshold RoP, who needed O2 to keep their saturation >94%, were randomized (average PMA 35.4 weeks) to a target of 91-94% or 96-99%. There was no difference in terms of progression of their eye disease, but the higher saturation target group had “increased risk of adverse pulmonary events including pneumonia and/or exacerbations of chronic lung disease and the need for oxygen, diuretics, and hospitalization at 3 months of corrected age“.

I haven’t found any study directly addressing the clinical outcomes of different saturation targets specifically for the group of preterm infants with BPD who also have proven pulmonary hypertension.

The AHA/ATS guidelines state “Supplemental oxygen therapy is reasonable to avoid episodic or sustained hypoxemia and with the goal of maintaining O2 saturations between 92% and 95% in patients with established BPD and PH (Class IIa; Level of Evidence C)” Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension: Guidelines From the American Heart Association and American Thoracic Society. Circulation. 2015 Nov 24;132(21):2037-99.

Similarly the PPHNnet guidelines have :”Supplemental oxygen therapy should be used to avoid episodic or sustained hypoxemia and with the goal of maintaining oxygen (O2) saturations between 92%-95% in patients with established BPD and PH. (class 1, LOE B)” Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Network (PPHNet). Evaluation and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension in Children with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2017 Sep;188:24-34.e1

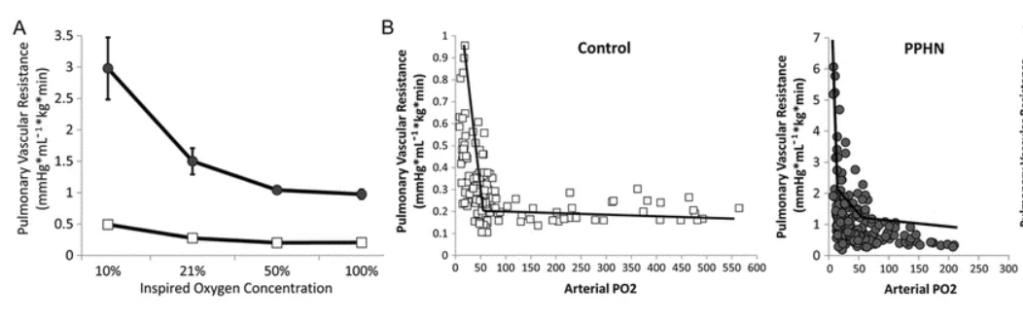

Indeed there are experimental data that show that once adequate saturation has been obtained, further increases in FiO2 do not decrease pulmonary vascular resistance, in normal lungs or those with PPHN.This graphic for example, from one of Satyan Lakshminrusimha’s animal studies, shows a decrease in PVR with increasing PO2 with a maximal effect at either 50 (control) or 60 (PPHN). Further increases in FiO2 had no significant impact on PVR, but do generate oxygen free radicals, and impede NO-dependent arteriolar vasodilatation.

The same group, in another model, showed that the minimal PVR was achieved with an SpO2 of 93-97%, which in this model required an FiO2 of 50%. Further increasing the FiO2 led to much higher PaO2, and SpO2 of 98-100%, but increased the PVR.

Given this, I found it strange to note that a publication supposedly presenting the European guidelines from the EPPVD (Hansmann G, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(3):446-55) suggests an SpO2 target of >95%, with no high limit. I tried to find the source of the data from this recommendation, and the only reference they give is to the 2019 consensus statement, which doesn’t actually recommend such high targets. Indeed that statement just states “The term or preterm newborn infant should receive oxygen, ventilatory support and/or surfactant if needed to achieve a pre-ductal SpO2 between 91% and 95% when PH is suspected or established. It is useful to avoid lung hyperinflation and atelectasis, or lung collapse and intermittent desaturations below 85%, or hyperoxia with pre-ductal SpO2 above 97%. (S9-1)—(S9-3)“, the SP-1 etc seem to refer to publications which aren’t actually very relevant. There are no other SpO2 recommendations in that statement. There don’t seem to be any data to support the recommendation of >95%.

In other words, despite a major lack of good quality data to show that different SpO2 targets in infants with chronic lung disease and pulmonary hypertension have an effect on important clinical outcomes, the consensus seems to be that 92-95% is probably best. Higher targets have no known benefits, and may increase pulmonary toxicity and adverse outcomes.

Avoiding intermittent hypoxia is probably important, for which prolonged caffeine therapy appears to be effective. The ICAF trial, presented at PAS this year, but not yet published, showed much less intermittent hypoxaemia in convalescing very preterm infants who were randomized to caffeine or placebo after about 34 weeks (about 80 per group). Of course these were not babies with BPD-PH, but if the same reduction in intermittent hypoxia occurs in that subgroup, which I have no reason to doubt, then there could also be an impact on pulmonary vascular resistance.

Infants with chronic lung injury and pulmonary hypertension are a very high risk group, good quality trials to inform the best therapy for them are urgently needed.

Amen — I’ve argued a similar line of thinking using Satyan’s data when teaching about neonatal pulmonary hypertension therapies. Thank you for this important summary and call for study.