I was confused by this new article published in the Journal of Pediatrics. I really don’t understand what the point of it is, except to try and discourage intensive care for one particular group of high risk babies (Guillen U, et al. Community considerations for aggressive intensive care therapy for infants <24+0 weeks of gestation. J Pediatr. 2024:113948).

The article title immediately alerts to the slant of the argument, apparently active intensive care for the most immature infants is “aggressive”, the authors justify this word by noting that Helen Harrison used it. Speaking as someone who was publicly attacked by Helen Harrison after a presentation I gave, in which I had noted that the long term outcomes of preterm infants were largely positive, I don’t find that justification adequate!

The authors of the article make a number of points that it is difficult to argue with: that outcomes are variable and uncertain; that decisions should be individualized and parents should always be involved; and that we should advocate for long term support for survivors and their families.

My question is: what is so different about this subgroup of babies? Surely the same things can be said about high-risk diaphragmatic hernias, or babies with severe variants of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, or babies born at 28 weeks after rupture of membranes at 20 weeks and persistent anhydramnios. Indeed, for each of those 3 examples, survival may be lower, and long term complications just as uncertain, as the baby born at 22 weeks gestation.

Surely all high risk infants, whatever their gestational age, have outcomes that are uncertain and variable, require individualized decision-making with parental involvement, and deserve long term support as much as they deserve active intensive care.

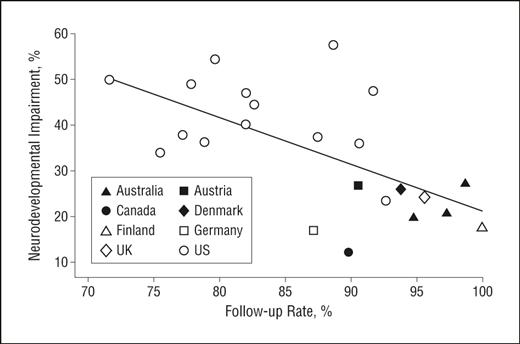

There are some other concerns about this paper, it is stated, for example, “As the rates of BPD were high, and BPD correlates with NDI, the loss to follow up may under-estimate rates of NDI” I don’t understand the logic of that sentence, unless there is some unstated evidence that infants with BPD have lower follow up rates. In fact the reference just given in the article, which was written by the first author of this new opinion piece, shows the opposite; higher follow up rates are associated with lower rates of “NDI”.

In that systematic review, it was shown that loss to follow up, on average, over-estimates rates of NDI. Which I presume is because infants who are doing well are, in general, less likely to be brought back by their parents for neuro-developmental assessment.

The authors also talk about the high rate of acute morbidity among the most immature infants, and it is true that a very high proportion have acute morbidity, including extremely high rates of BPD. But, still needing oxygen at 36 weeks is a consequence of exposing fragile and extremely under-developed lungs to oxygen and positive pressure, and doesn’t necessarily have huge impacts on the baby’s future quality of life. 2 of the other 3 examples I gave of high risk babies also have a very high incidence of chronic respiratory problems, and extremely high proportions have acute morbidity.

I think it would have been much more useful to point out that survival and other outcomes among these babies are extremely variable, but that with a consistent approach, co-ordinated with our obstetric teams, good survival is possible, and we should all be striving to institute best practice. They could also have indicated where to find the best information about how to improve survival and outcomes of these babies.

The Tiny Baby Collaborative has been developed in an attempt to improve the outcomes of such infants, their website gives you access to several recent Webinars. One interesting aspect of which is that the approach to such infants differs in many important details from one successful centre to another, in terms of fluid management, ventilatory approach, etc. What is universal in such centres is a collaboration with obstetrics, consistent, protocol-driven, approaches, and a commitment to and belief that these babies are worth the effort. I don’t find it useful to define one category of babies that are not worth as much as others; it is not many years since people were saying exactly the same things about babies born at 24 weeks. With “aggressive” quality improvement initiatives, survival is now over 70% across Canada, it has become infrequent to not start intensive care for such infants, and huge numbers of families, including my own, have benefited from a refusal to suppose that we have arrived at a limit of viability, but rather to push the barriers and progressively improve our care processes.

Keith – you always make us think. I really appreciate the opportunity for thoughtful dialogue. Best Always! Madge Buus-Frank

My suspicion is that this is written in the context of the prevailing political climate in the US and the concern that the setback in women’s reproductive rights may prompt re-evaluation of parental decision making rights regarding resuscitation of peri-viable infants.

Thank you Keith,

Very thoughtful.

Discouraging opinions about providing active care to immature infants keep coming (as they have been for the last 30 years or so…), at least where I practice exclusively from professionals that rarely, or never, care for these infants and their families.

We as a community should really avoid such “charged” terminology. When did respiratory support, skin-to-skin care, and breast milk become aggressive? And – in what way are treatments tailored to smaller body sizes “high-tech”??

Johan Agren, Uppsala, Sweden

Thank you, Keith, for your inspiring posts. I defended my thesis recently, based on 2 papers about the perinatal management of infants born at the limits of viability in Spain in last 15 years. Most of my comments and opinions are same by yours: cooperation between obstetrical and neonatal teams and a robust intention to treat are the clues. Decisions shouldn’t be longer based on gestational age. The quality of life and long term outcome use to be underated by those professionals who don’t follow up former premature infants.

Keith,

Thank you.

You hit the critical points in your comments, some of mine are repetitive, but you opened a door here.

It is well acknowledged that tinier babies pose greater challenges for survival but it has always been the case. I have seen the limits of viability move from 26 then 25 then 24 and now 23-22 weeks over my neonatal life, with variability in the limits in those units compared to other nearby units. In reviewing the literature back into the 1990s on this topic, with each step we have always rightly raised concerns noted by Guillen et al. I also agree with the concerns raised by Dr. Jobe, in one of the Guillen references, that at some point the developmental biology of the premature body, especially the lung, may not be able to accommodate, even if abnormally, to the ex-utero environment. Many of us thought it would be 24 weeks, or 23 weeks, maybe it is 22 weeks. Or not.

Keith you make the vital point that in all we do, but especially for these more fragile infants, a truly collaborative approach, a tiny baby shared model, is necessary. It should be a key driver for higher level units currently caring for 23-22 week babies to explore and develop such methods.

The authors in Guillen et al. make several points and statement which are disturbing though.

I simply don’t know any neos who eagerly anticipate the delivery of the world’s tiniets baby in order to trumpet and advertise their care.

The use of terminology like “aggressive”, justifying its use on an Ohio law which was likely influenced by physician advisors who used the term, exhibits extreme prejudice regarding such care. This is language we have routinely apply to care in the NICU that is viewed as “excessive” but we were pursuing it. Similarly, we use language like “do everything” to describe the wishes of families seeking what is not infrequently standard care for a baby that has a GA a few days or a week older, or a baby with normal chromosomes instead of a trisomy. In fact there are many similarities here between the care we do or do not offer tiny babies and the care we do or do not choose to offer to families of children with trisomy 13 or 18. Bias abounds.

The authors should have explored a little further the background of the Ohio law they reference as the reasonable basis for using the term “aggressive”. Emery and Elliot’s Law was passed in Ohio in response to a case of twins at 22 weeks GA. Mom was admitted at 22 2/7 weeks and was promised that if babies were born at 22 5/7 weeks or later, they would receive support. They were born at 22 5/7 and no supportive care was offered and after a few hours the babies died. First, it seems absurd that we as neos would designate 22 5/7 weeks as a marker for intervention given all the uncertainties surrounding dating, but secondly, how, after promising this, would we not at least attempt resuscitative care?

The concerns in this case aside, generally, if a NICU team is providing care to a 26 week IUGR infant without antenatal steroids requiring intubation in one room and a second team is intubating an AGA 22 week infant whose mother received a full course of antenatal steroids in the next delivery room, which team is employing “aggressive” maneuvers? As some like Wilkinson have pointed out, isn’t this gestational ageism? Also such situations should require us to consider less the gestational age of a potential preterm delivery and more the surrounding circumstances. We know there are inaccuracies in dating. We know oligohydramnios or PPROM is problematic in many cases. Etc.

What the article never discusses, but should, is while there is variable belief in the merit to attempting to support the tiniest babies, there is variability between hospitals at a “policy” level. And often between hospitals located in the same geographic region. It is not an uncommon scenario that a mother in preterm labor at 22 weeks will be admitted to a hospital with a Level III or IV NICU whose “policy” is we do not resuscitate infants less than 23 weeks. Some might still be at a 24 week threshold of viability even if parents desire intervention. However, a hospital across town or across the county will resuscitate that baby. Rysavy has well demonstrated in older work the significant variation amongst hospitals in the willingness to resuscitate such infants. These policies then dictate survival. This is what led to Emery and Elliot’s law and a requirement that hospital’s need to disclose their resuscitation policies and if parents desire, and it is deemed safe for a mother, that a transfer occur to a hospital that will accommodate the intentions of parents expecting an extremely preterm birth…or birth of child with a disability. This law did not mandate a NICU provide care they felt was too “aggressive”, but that we as physicians adhere to a foundational principle in medical care….informed consent.

This discussion is as much about informed consent and overcoming our own biases as much as it is about the lack of data regarding outcomes, or a need to continue to gather data on the outcomes of tiny babies which we would all agree on. The arguments against advancing the limits of viability have been made for every GA in my time as a neo…going from 28 to 26 to 24, now what about 22-23. This is not news. And yes we want data, not just on survival but long term outcomes to inform parents, but the fact is some of us have well established in our local experience that we can achieve survivals and outcomes we would never have thought possible 20 years ago. Our concerns aside, parents have the right to know what is possible, what the risks are and be allowed to make informed decisions. I know personally of cases where a family was told our hospital policy is no resuscitation under 23 weeks gestation while in the area was a hospital with a different policy and reasonable survivals and outcomes for 22 week babies. The parents only knew this by inquiring on their own on the internet and with friends in the city. This mother in early preterm labor had to request transfer to the nearby hospital where she received antenatal steroids and delivered her baby at 23 plus weeks. It should not be this way.

The authors state, “To provide full transparency, counseling has to incorporate both current data from the literature and up to date data from the geographically nearest local database to be applicable to the parent being counseled.” Is such counseling a universal rule? Are those not resuscitating 22 week, or even 23 week infants, routinely advising parents that there may be a reasonably located NICU that will do so and we can arrange transport? We are doing this on a regular basis in NC, is it being done nationally?

Last the article clearly seems to point towards the tendency by some of us to consider death and poor NDI outcomes as two sides of the same coin. The bias of the authors reporting in the article appears to be to consider them similarly in the sense that we seem to be told to throttle back life saving interventions for tiny babies pending more NDI data. This should not be the view of physicians, even if it may be personally your view. Some families might consider death and NDI to be the same, some will not. Should these risks be discussed with families making resuscitation decisions at extreme gestations? Certainly. The fact though that infants that will survive at lower gestations will experience high rates of moderate to severe NDI is not a reason, however, for us as physicians to deny a family and baby the opportunity for life or offer safe transfer to a nearby facility willing to attempt to support the care a family desires after being fully informed.

The authors in conclusion make an unusual statement. “Forcing a trial of therapy on families who prefer comfort care measures reduces their medical autonomy and raises the question of whether shared decision-making and respect of cultural, social, and religious pluralism is present. Informed decisions need to be respected. There is no single ‘correct’ decision for every patient or family.” This is a strawman. In no neonatal quarter have I heard cries coming up from neos demanding “forcing” resuscitation on an infant at 23 weeks or less. Rather what many parents and neos are advocating is the possibility of such intervention be offered as a standard part of informed consent, even if the hospital receiving the mother does not feel capable of offering such care. In those case a safe transfer of care could be offered. If there is no time for such transfer and parents desire resuscitation for their 22 week baby, as a neo in a facility with a policy of not attending such deliveries at our hospital. I would personally feel obligated to resuscitate and stabilize the baby and arrange transfer to a center with greater expertise in caring for such babies. Similarly we not uncommonly receive preterm babies from outlying community hospitals resuscitated in the ER by a capable team. The hospital cannot care for such infants but we accept them as transfers.

So I just don’t see many wishing to force 22-23 week resuscitations on families, but it sure does seem the authors are making the case to discourage such interventions and offering it to parents.

Keith, the esteemed Dr. Janvier has taught me well that “shared decision” making is prone to bias. The authors report on one possibility, the providers and family agree on a shared plan, presumably based on a full presentation of all the pertinent facts and parents and care team reaching a consensus. The authors also discuss consensus decisions and the family asking the team to make decisions. These seem to be the “shared” decisions we as healthcare providers are most amenable to. The authors do not mention a third scenario…that some families want to make their own decisions independently after receiving adequate informed consent regarding paths for care. This is the scenario that led to the passage of Emery and Elliot’s Law. The parents chose a path the team agreed to, seemingly reluctantly, but in the end would not even accommodate.

From Dr. Janvier, “The goal of antenatal consultation should rather be to adapt to parental needs and empower them through a personalized decision-making process.” I think personalized encompasses better what we should be aiming for with families. The decision arrived at should always be based on transparency and all necessary information, but it may not necessarily be a shared view.

Last, I truly wish that we as neos would look at a conversation like this and extend it to our care of infants with trisomy 13 and 18. The same principles apply. These conditions are not lethal or incompatible with life. Life limiting yes, though aren’t we all life limited? Despite increasing reports of extended survivals of these children with medical interventions, there remain calls for halting such interventions pending “more data” on quality of life and the impact these children have on their families. So we see a similar double standard in care where some centers have pursued medical and surgical interventions for such patients, with survivals we were told were impossible a decade ago, while many, certainly not all, continue to only offer hospice care, perpetuate beliefs of no hope for any extended life, and no information related to the potential for medical interventions at other centers that not only prolong life, but prolong lives that families describe as high quality despite serious mental and motor impairments.

Thank you again Keith.

Marty

Keith-

Thanks a lot for the through review. If we did not have eagerness to treat extremely premature babies 30 years ago, we would not see them alive currently.

Our enthusiasm to offer these tiny, “peri-viable” babies a chance to survive and work hard on improving the outcome is the whole thing about the neonatal care. It is a challenge, and we have to try our best go through it. We will succeed at one point similar what we did with 26 weekers some years ago.

Best regards,