Delayed cord clamping has, rightly, become the default whenever a newborn infant is born, benefits in term, late preterm, and very preterm infants have been shown. Current guidelines suggest that if the infant “needs resuscitation” then immediate clamping and assisted ventilation is reasonable. But, if the baby does “need resuscitation” then the best approach remains uncertain. I can do no better than quote from the introduction of the published protocol for the ABC3 trial (which was actually an abbreviation for “Aeration Before Clamping”).

Recent meta-analyses, comparing delayed cord clamping (DCC) with immediate cord clamping (ICC) in preterm infants, showed increased haematocrit, fewer blood transfusions, a decrease in mortality and a trend towards fewer intraventricular haemorrhages (IVH). However, in most studies, DCC was performed using a fixed time of 30–60 s, while it can take up to 3 min before placental transfusion is complete. Waiting longer than 30–60 s is not considered feasible, given that respiratory support cannot be applied during this time interval. Additionally, most trials comparing DCC to ICC did not include very preterm infants requiring immediate interventions for stabilisation or resuscitation, while these infants have the highest risk of complications and therefore could benefit most from DCC.

…recent studies in preterm lambs have demonstrated that delaying cord clamping until after ventilation onset prevents a rapid decrease in cardiac output. The observed large fluctuations in systemic and cerebral haemodynamics, and concomitant bradycardia and hypoxia frequently observed in preterm infants after ICC, could be avoided by delaying cord clamping until after aeration of the lung… delaying cord clamping until the infant is stabilised may decrease the risk of cerebral injury and hypoxia-related diseases such as NEC and associated rates of mortality and morbidity.

As you can probably tell by the quotation marks around “needs resuscitation”, I think it is really unclear when a non-vigorous infant who is still attached to the placental circulation should have resuscitation instituted. If the infant is apnoeic at birth, but with a good heart rate, should you clamp immediately or wait for a short time while stimulating the baby, or just wait and watch, if the cord is pulsating, with the hope that the baby is getting adequate oxygenation from the intact placental circulation?

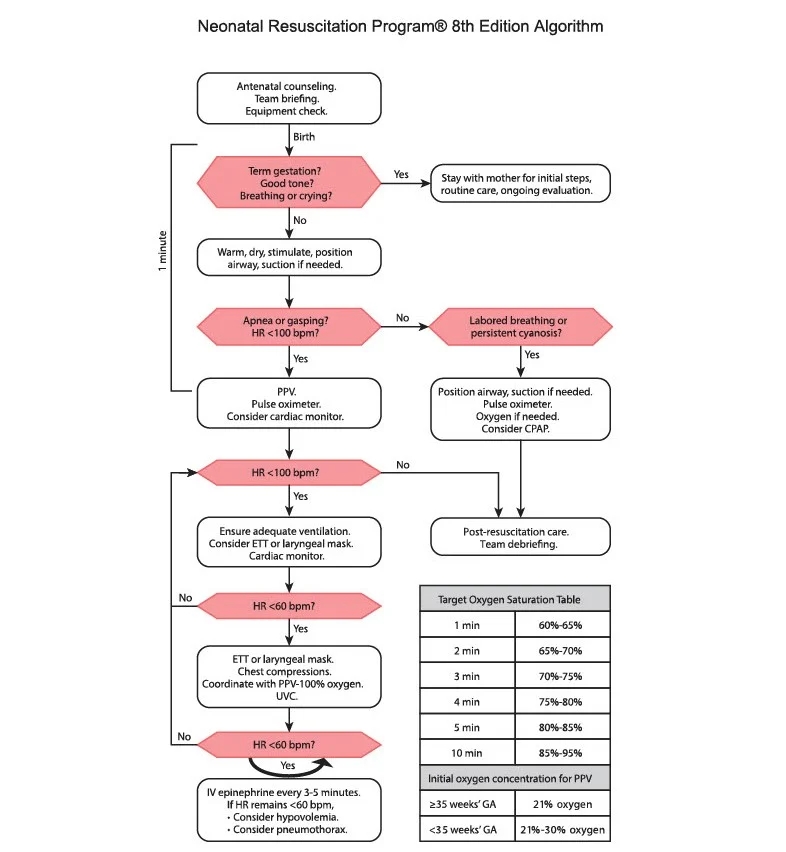

Indeed the current NRP algorithm doesn’t mention cord clamping anywhere!

The most recent European guidelines (Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rudiger M, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation. 2021;161:291-326) are clearer on this issue, they have an introductory section as follows

Management of the umbilical cord after birth

- The options for managing cord clamping and the rationale should be discussed with parents before birth.

- Where immediate resuscitation or stabilisation is not required, aim to delay clamping the cord for at least 60 s. A longer period may be more beneficial.

- Clamping should ideally take place after the lungs are aerated. Where adequate thermal care and initial resuscitation interventions can be safely undertaken with the cord intact, it may be possible to delay clamping whilst performing these interventions.

- Where delayed cord clamping is not possible, consider cord milking in infants >28 weeks gestation.

They divide babies into 3 groups; Group 1 is “satisfactory transition”; babies who should have delayed cord clamping. Group 2 is “Incomplete transition”:

I’m not sure about the inclusion of ‘reduced tone’ in this: what if a baby is hypotonic (and I am not sure how good we are in the DR in evaluating the muscle tone of a baby) but breathing well with a good heart rate? Even ‘breathing inadequately’ is somewhat subjective, it is mentioned elsewhere in the guide that this refers to gasping or grunting. The guideline continues with the following recommendations

- Dry, stimulate, wrap in a warm towel.

- Maintain the airway, lung inflation and ventilation.

- Continuously assess changes in heart rate and breathing If no improvement in heart rate, continue with ventilation.

- Help may be required

The 3rd group in these guidelines are “poor/failed transition”

Again, although most babies with apnoea and/or bradycardia are floppy, why does that need to be there? Surely it is the respiratory and cardiac status that are important.

The guidelines further note :

Preterm Infants

- Same principles apply.

- Consider alternative/additional methods for thermal care e.g. polyethylene wrap.

- Gently support, initially with CPAP if breathing.

- Consider continuous rather than intermittent monitoring (pulse oximetry ECG)

It isn’t clear how long the initial assessment of breathing and heart rate should take, and if you can wait for 10 or 20 seconds or longer to see if the infant starts to breathe. There is a section on tactile stimulation which states

- Initial handling is an opportunity to stimulate the infant during assessment by

- Drying the infant.

- Gently stimulating as you dry them, for example by rubbing the soles of the feet or the back of the chest. Avoid more aggressive methods of stimulation

But I can’t see anything about how long to continue the stimulation. I know this is a minor point, but when we start to consider whether, and when, we should progress to more invasive support prior to clamping the cord, it starts to become more important.

There is a later flow chart in these European recommendations which suggests that, for the apnoeic baby, we should have opened the airway and given 5 positive pressure breaths by about 60 seconds of age.

The reason for me nitpicking over these guidelines, and noting that the NRP/AAP/CPS guidelines are unclear on the cord clamping issue, is the publication of a multicentre RCT (Fairchild KD, et al. Ventilatory Assistance Before Umbilical Cord Clamping in Extremely Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(5):e2411140)

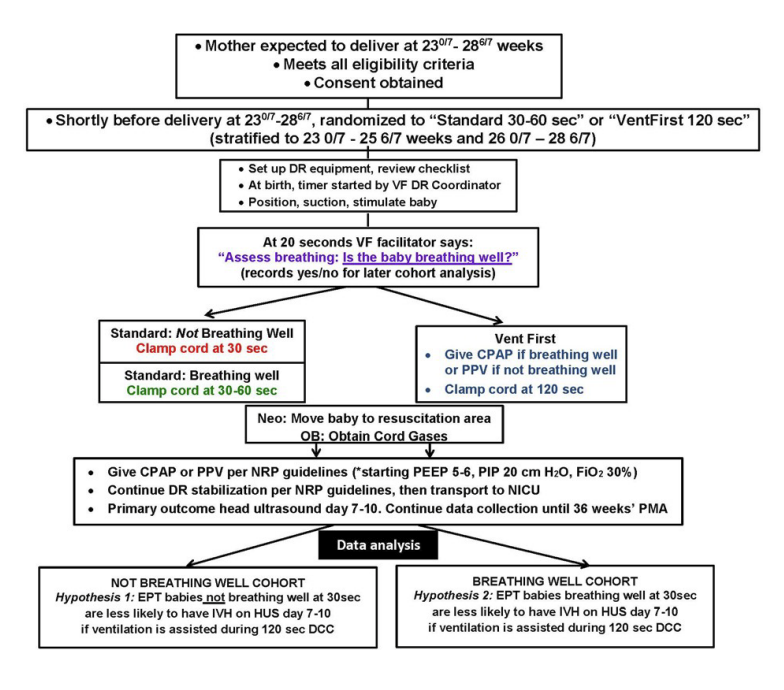

Infants <29 weeks were randomized to the intervention group with assisted ventilation before cord clamping, or control, standard, care. Below are lightly edited extracts from the methods section.

In both study groups, initial steps of infant resuscitation included tactile stimulation and suctioning the airway, if needed.

Immediately after delivery, infants were placed near the perineum for vaginal birth, on sterile-wrapped trays across the mother’s thighs for cesarean birth, or on freestanding platforms for initial steps of stabilization. Warming pads and plastic wrap were used to minimize heat loss. Thirty seconds after birth, the infant received CPAP if breathing well or PPV if not breathing well. Heart rate was checked at 60 and 90 seconds, and if <100, ventilation corrective actions were performed per NRP. The goal cord clamping time was 120 seconds after birth. Equipment used for the intervention varied by site and included face masks, devices to administer CPAP and PPV, oxygen and air tanks to provide blended supplemental oxygen. For cesarean deliveries, equipment was near the sterile field.

For infants randomized to the control group, the umbilical cord was clamped 30 seconds after birth if the infant was not breathing well (apnoeic or gasping), or delayed until up to 60 seconds if the infant was breathing well (audible crying or visible sustained respirations).

The flow diagram of the protocol in the supplemental materials is helpful:

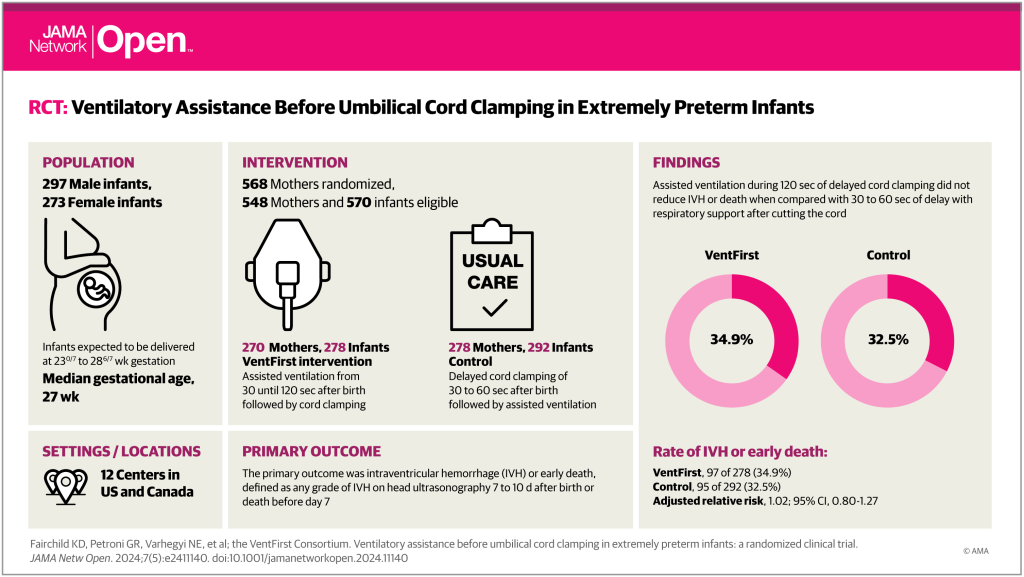

The primary outcome of the trial was survival to 7 days of life without any grade of IVH.

The trial was powered for an Odds Ratio of 0.5 among the “Not breathing well” group of the primary outcome. Although it was an unmasked study, for obvious reasons, the evaluation of head ultrasounds was performed by independent masked radiologists.

The overall findings were of no difference in the primary outcome, as you can see from the weirdly pink visual abstract. In more detail; among the subgroup who were not breathing well, there was the biggest difference in the intervention, with the controls having cord clamping at 30 seconds, transfer to a resusc table followed by further intervention as required, and the VentFirst group who had assisted ventilation, and other manoeuvres, with the cord intact for 120 seconds.

In the ‘not breathing well’ group mortality at 7 days was similar: 11% control, 9% VentFirst; and any IVH among survivors to 7 days was 32% vs 30%. Strangely, the RRs were a little <1 for mortality and a little >1 for IVH, even though both were slightly more common in the controls, I wonder if there is a mistake in those numbers.

In the babies who were breathing well, in whom the difference in intervention was really just in the duration of DCC, the results are reversed, with both mortality and IVH being slightly more frequent in the VentFirst group, and both RRs being >1.0, although with tiny numbers of deaths.

Regular readers will probably guess what I am going to say now, which is “who cares?” Who cares about deaths by 7 days of age, or grade 1-2 IVH? Surely, what is really important is whether the babies were more or less likely to go home alive, and whether they had a brain injury which could increase their chances of a limited long term outcome. For the first part of that concern there is no data presented in the manuscript: but there are data on survival to 36 weeks, which was 26/278 VentFirst babies, and 29/292 controls. As there are usually few deaths between 36 weeks and discharge we can hope that survival to discharge was not different between groups, there were about 1/5 of the babies who were <26 weeks, in whom late death is a bit more common, but I guess we won’t know for sure about survival to discharge unless long-term follow-up is published. As for more serious brain injury, there is a secondary, composite outcome, of grade 3 or 4 IVH, cystic PVL, or cerebellar bleeds. This outcome was, in the subgroup who were ‘not breathing well’, somewhat less frequent in the VentFirst group than controls, 11% vs 18% (RR=0.63, 95% CI 0.35, 1.13), and a little more frequent in the VentFirst group among those ‘breathing well’ (9% vs 7%). After scouring the supplemental material, the frequency of combined grade 3 and grade 4 IVH was 13/150 vs 18/121 (‘not breathing well’, VentFirst vs Control), and 8/128 vs 9/171 (‘breathing well’ groups).

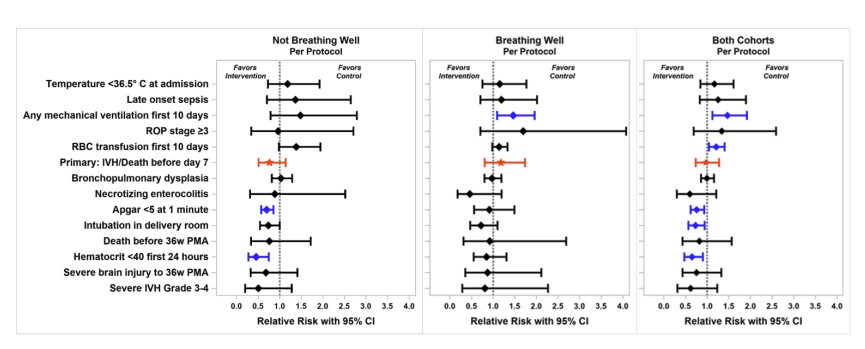

Among other outcomes that were measured, VentFirst babies had higher 1 minute Apgars and were less likely to be intubated in the DR (47% vs 62%). All other usual neonatal outcomes were very similar between groups. Of note the median duration of DCC in the VentFirst group, which was supposed to be at 120 seconds, was actually 105 seconds, with the 25th percentile being 20 seconds in the not breathing well group (75th percentile = 122 seconds). So large numbers of babies were protocol violations. The authors have also, therefore, performed a “per-protocol” analysis, in which the 413 babies who had DCC within 15 seconds of the time prescribed by the protocol are included. As you can see in the figure below, all the confidence intervals cross the 1.0 line, and there were no striking differences in these outcomes either. The babies who really did have more delayed DCC had less anaemia, but the primary outcome was not very different between groups. It looks like there might be a signal there of fewer grade 3 and 4 IVH, at least among the ‘not breathing well’ subgroup, but it could be just a chance difference.

I know it is easy to be critical while tapping away at a keyboard, I also recognize that study design is always a compromise, between what is ideal and what is practically possible. But I do think that outcomes of more interest, such as survival to discharge without major brain injury, or, preferably, a prioritized composite with death before discharge being the worst outcome, followed by major IVH, would have been just as feasible with a similar sample size.

If we were to assume that there were no deaths between 36 weeks and discharge, then the alternative outcome of “death or severe brain injury” occurred in 54/278 VentFirst vs 63/292 control babies, which doesn’t look like an important difference; death before 36 weeks was 26 vs 29, and serious brain injury was 28 vs 34, neither of which are striking differences.

The same investigators previously published a pilot study with 29 babies <33 weeks GA. They don’t present any clinical outcomes in that report, but do mention one death in a baby incorrectly randomized, which makes me think that all the others survived.

The ABC3 trial was presented at the JENS in Rome last September, in that trial eligibility was <30 weeks GA, and the intervention group had resuscitation with an intact cord until the baby was stabilised, rather than for a fixed duration, the planned timing of cord clamping was between 3 and 10 minutes. Stabilisation was defined as a good heart rate, and a saturation over 85% with <40% oxygen. The presentation noted that there was no difference in the primary outcome, which was survival to discharge without IVH of 2 or more and without NEC of stage 2 or 3. JENS doesn’t publish abstracts for all of the presentations, so I can’t give any more details. However, the pilot for that trial has been published (Knol R, et al. Physiological-based cord clamping in very preterm infants – Randomised controlled trial on effectiveness of stabilisation. Resuscitation. 2020;147:26-33). In the pilot 37 infants were included, with the primary outcome being time to stabilisation, which was shorter in the intervention group. In the pilot all clinical outcomes were very similar between the 2 groups.

The ABC trial has also previously been published (Nevill E, et al. Effect of Breathing Support in Very Preterm Infants Not Breathing During Deferred Cord Clamping: A Randomized Controlled Trial (The ABC Study). J Pediatr. 2023;253:94-100 e1), a single centre RCT enrolling babies <31 weeks GA. In that trial, infants in both randomized groups had the cord clamped at 50 seconds, the best way to describe the protocol is with the figure from the published protocol.

As you can see, apnoeic infants (happy to see the correct spelling!) were either ventilated with the cord intact, or just had stimulation and positioning, from 20 to 50 seconds after birth. 113 babies were enrolled and studied, with the primary outcome being transfusion requirements. Neither transfusion need, nor any other clinical outcomes (death, 9% vs 7%, or IVH grade 3 or 4, 11% vs 9%, or the usual clinical outcomes), were different between groups.

It seems to be becoming clear, that the major extra logistic problems associated with providing respiratory resuscitation of very preterm infants before cord clamping, which in ABC3 involved inventing a special table for resuscitation, do not seem to lead to any substantial benefits. Below is a photo of the beast invented for, and used in, ABC3, called the “Concord”.

It is appropriate to wait for the full publication of ABC3, and perhaps other trials, before completely abandoning this approach. For now, the evidence-based approach for the moderately preterm baby, and for the more immature infant, is to evaluate the infant at birth with the cord intact, and if possible to delay cord clamping for 30 seconds, which I think is reasonable even in an apnoeic infant unless they are bradycardic. During that period of DCC the infant should be kept warm, and put in a plastic bag without drying, possibly additional gentle stimulation is reasonable during this 30 second period. If, after 30 seconds the infant is still apnoeic, then clamping and cutting the cord should proceed, and the baby resuscitated on a regular resus surface. If the baby starts to breathe before the 30 seconds, then DCC can be prolonged.

If you have already bought a Concord, or other similar table, then there doesn’t seem to be any harm of starting assisted ventilation prior to cord clamping, and this might decrease the need for early intubation, and shorten the time to stabilisation. However, as far as we can see at present, that doesn’t lead to any other clinically important advantages.

Dr. Barrington: Thank you for the summary of these important trials. To clarify, the 8th edition of the AHA/AAP NRP textbook, published in 2021, is neither silent nor unclear about cord clamping. While it is not included the 8th edition algorithm, which focuses on resuscitative steps after cord clamping, it is discussed in the text. For NRP readers, the simple recommendation is listed as a key point on page 35 (Lesson 3), additional context supporting the recommendation is summarized on pages 37-38 (Lesson 3), and specific recommendations addressing controversies related to preterm infants are presented on pages 226-227 (Lesson 8). Establishing the cord management plan is included as one of the 4 questions to ask before every birth (Lesson 2) and examples of umbilical cord management strategies are included with each Case at the beginning of every lesson. The AHA Guidelines (Aziz K. Pediatrics 147 (S1), 2021) describe cord management on the first page (Take home message #2) and the details are described on pages S167-168.

Thanks for this, and thank you for your contributions to the NRP and the very important guidelines, which have become progressively more evidence-based as the years have gone by.

I probably overstated the “silent”, but the algorithm starts with birth, not with cord clamping, and clearly has an arrow at the side, for the duration of birth to 1 minute at which time you will have suctioned, stimulated, ‘positioned’, and started PPV if the baby isn’t breathing. Cord clamping is nowhere there. And maybe it shouldn’t be, but I think it would have been preferable to put, as one possibility, “either clamp and cut the cord and transfer the baby to a resuscitation surface, or start PPV with the cord still intact” in there at some point, probably at the point of asking “apnea or gasping?”

As it is, the algorithm, at least, is silent about cord management. The text you refer to is a very brief summary of the review of the literature (not a criticism, it was supposed to be brief) and really just says, there are “insufficient studies to make a recommendation for infants who require resuscitation” about delayed clamping. Which is true on the one hand, but the lack of evidence didn’t stop the writers from recommending tactile stimulation, for which there is no controlled evidence quoted in the guidelines or anywhere as far as I know. I think the NRP guidelines are so important, and so influential, that just to say “er.. we don’t know” was a mistake. Better to say something like “clamp the cord at this point for further resuscitation, unless taking part in a trial”. This could even have been an option at more than one point, you probably don’t want anyone starting cardiac massage with the cord intact, so at that point it could state, “clamp the cord now if not already done”.

The reality is that the start of the algorithm, every baby in the world is attached to the cord, and it has to be clamped and cut at some point. Surely there should be some guidance, other than “we don’t know” on what to do if the baby needs resuscitation?

As it is these new trials, published after those guidelines, strongly suggest little benefit (and no real harm) of prolonging DCC once the infant needs assisted ventilation.

Keith, I enjoyed reading your summary and agree with many of the points you make but believe that you have overlooked a couple of important issues.

The VentFirst study that you highlighted and discussed was unfortunately limited by the maximum cord clamping time of 120 seconds in the treatment group, with many not reaching this time. I agree that study designs often reflect a compromise due to practical and logistical issues and that it is also easy to see short comings in retrospect. However, the recent individual patient data network meta-analysis of delayed cord clamping in preterm infants clearly shows that a delay of >2 minutes has a 91% probability of being the best treatment. Delays of

I believe that you have also overlooked the issue of how experience with a medical procedure can influence outcomes. Indeed, if somebody had written a summary on the use of kidney dialysis machines after the first couple of studies, I believe that they would have summarised their effectiveness in the same way you have regarding the resuscitation of preterm infants on the cord. That is: “the major extra-logistical problems…. do not seem to lead to any substantial benefit.” Luckily for patients with renal failure, these pioneers were not so easily swayed. While I am not trying to equate the medical conditions or outcomes of the two, the presentation of ABC3 at JENS did highlight a substantial effect of experience on outcome, which should not be ignored.

I also disagree with your comments about “who cares about deaths at 7 days or grade 1-2 IVH” and consider that this philosophy places an unnecessary “roadblock” in our capacity to improve outcomes for very preterm infants. In my opinion it is unrealistic to expect that a single delivery room treatment, by itself (including resuscitation on the cord), will increase the odds that a child will “go home alive… and without brain injury”. Thus, to use this as an outcome in a clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of a single treatment in the delivery room is in my opinion, illogical. It would be similar to NASA testing the performance of its main rocket engines at lift-off by assessing whether the astronauts returned safely from the moon. While “lift-off” is a critical component of the mission, it is only one component that determines the success of the mission. Yes, the wider public and politicians are only interested in whether the astronauts returned safely, but the engineers would never contemplate using this as an outcome measure for rocket engine performance. However, I think that this is what we are doing when using “home alive without brain injury” as the only “meaningful” outcome for delivery room treatments.In my opinion, improving outcomes for very preterm infants is going to require several packages of care that differ as the infant progresses from the delivery room into the NICU and beyond. However, as these “packages of care” are comprised of multiple components, to construct the most beneficial package that can improve “death or disability at 2 years”, the benefit of each component needs to be assessed and they need to be assessed with respect to the benefit they provide. Then when all components are shown to have benefit, test the entire package using death or disability as the outcome. If we do not understand the benefit of each component, we are simply guessing as to what components should be included, which is far from ideal and one could argue is the current status. It is relevant to note that this is what created the issue of immediate cord clamping in the first place. That is, it was included in a package of care called “Active management of the 3rd stage of labour”, to reduce the risk of post-partum haemorrhage (PPH). This package was comprised of (i) administration of uterotonic upon delivery of the anterior shoulder, (ii) immediate cord clamping and (iii) gentle traction on the cord to deliver the placenta. While successful at reducing the risk of PPH, it was subsequently shown that, of these components, only uterotonic administration reduces the risk of PPH. In contrast, immediate cord clamping was shown to be detrimental to the infant (reduced birth weight and low heart rates) and cord traction had no effect. It is only by assessing the benefits of individual treatments in the correct context that we will be able to avoid making these same mistakes. As per the moon mission, I believe that achieving a successful lift-off is akin to progressing the infant out of the delivery room in as healthy a condition as possible. The success of the rest of the journey then depends on a separate series of criteria which may or may not be related to what happened in the delivery room (lift-off).

Thanks for the thoughtful comments, Stuart. You are always worth listening to and it is because of much of your work that we have been improving delivery room care for babies.

All studies have limitations, and you have pointed out one of the important limitations of Ventfirst, and, as I pointed out in the post, even the 120 second delay was not adhered to for large numbers of the Ventfirst group. I get your point with the lift-off analogy, but, I would say, that is why we do large RCTs, in which all of those other factors involved in good outcomes will balance out on average between groups. It is more like NASA comparing the performance of its rockets by firing off 250 with design A, and 250 with design B. Even if A is more likely to get you into orbit, if it costs 3 times as much, and you still don’t get more success in your moon mission, then perhaps they would go with design B anyway!

Unless a new intervention can be shown to have a clinical advantage, then the extra training and expense and logistical problems are difficult to justify. It is very important to choose outcome variables that have some chance of being related to the intervention, and also have some significance for the life of the baby.

To get back to earth, the point about severe IVH, rather than lower grades of haemorrhage, has a number of parts to it; for example, there is a problem with the accuracy of diagnosis, as well as the implications for the short term and the long term. There actually looks like a possible signal of benefit for more severe IVH in the outcome data, grade 3 and 4 IVH combined occurred in 8.6% of the Ventfirst group, and 15% of the early clamping group, among the “not breathing well” group. That is a major potential impact of Ventfirst, which is ignored because it is not “statistically significant” but might be a huge advantage, if it can be confirmed in the future. Including relatively trivial IVH (I know they are not all trivial, and having even a grade 2 IVH has impacts on families) actually risks diluting out a real advantage of an intervention.

I do agree that the outcome variable “alive without major brain injury” is probably not the best for a DR intervention, which brings me back to the use of hierarchical prioritized outcomes, which can account for potentially conflicting outcomes, such as death or severe IVH, as one example. If you die on day 2, you may not have a diagnosis of a severe IVH, but if you have a better transition, that could have a whole sequence of potential benefits. Some of those benefits, such as NICU admission, for example among late preterm babies, could well be better with a more physiological transition, but without an impact on mortality.

As for a “learning curve”, this is a big problem, I agree, I seem to remember, although I don’t know if it was in the final publications, that in the APTS trial, the proportion of babies who were randomized to delayed clamping, who actually got early clamping, decreased substantially during the trial, as the trial progressed, and people became more comfortable with waiting to clamp the cord, and not jumping in and clamping early in order to resuscitate. I don’t remember the presentation of ABC3 well enough, but if there was a progressive change during the trial, that is something that needs to be analysed carefully.