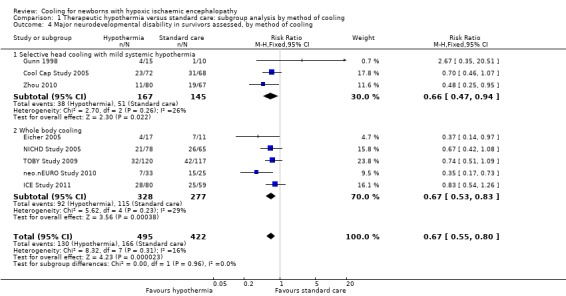

One of the numerous major advances in neonatology during my career has been the introduction of therapeutic hypothermia for infants with Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE). Mortality is decreased, by about 25%, and long term morbidity among survivors is also decreased, by about 33%. Those estimates of effect size come from the Cochrane review, which provides the following Forest plot (I’m sorry about the quality of the image, the version in the pdf of the review is much clearer, but it extends over 2 pages, with a page break in the middle).

The Cochrane review also analyzed the impacts of cooling after dividing the infants according to severity of HIE, confirming that moderate and severe HIE both benefit. Unfortunately, the long term outcomes have been reported mostly up to 2 to 3 years. In the Cochrane review, 6 year outcomes are only available for the NICHD trial, which reviewed 120 survivors at 6 years, CP, IQ <70, executive function score <70, and moderate/severe disability were all lower in the hypothermia group than the controls, but the differences were small (and not “statistically significant”). The Cochrane review dates from 2013, and in 2014 the TOBY trial from the UK published follow up to 6-7 y of age, they showed more babies surviving without disability in the hypothermia group and “Among survivors, children in the hypothermia group, as compared with those in the control group, had significant reductions in the risk of cerebral palsy (21% vs. 36%, P=0.03) and the risk of moderate or severe disability (22% vs. 37%, P=0.03)”. Executive function scores were also higher in the cooled babies, and full scale IQ was 5 points higher (NS).

This new study has examined survivors of HIE and cooling sequentially, at 2y, 5y and 8 to 10 years, from 2 Dutch centres Parmentier CEJ, et al. Serial Assessment of Neurodevelopmental Outcome Following Neonatal Encephalopathy and Therapeutic Hypothermia. J Pediatr. 2025;285:114679. They used, appropriately, different tools at each age, each of which is normalised for the general population at that age, BSID ver 3, WPPSI, WISC, and other motor scales were used. The Child Behavior Checklist was also used for all children at the 2 later visits.

Scores on motor function scales were progressively worse as the children aged. Behavioural problems became more prevalent. Cognitive scores were overall fairly stable, but there was a progressive decrease in cognitive scores in the subgroup of infants who had damage to the mammillary bodies on MRI.

Another very recent article along the same lines, from Coimbra in Portugal, Vicente IN, et al. Neurodevelopment in the transition to school in children subjected to hypothermia due to neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A prospective study. Early Hum Dev. 2025;207:106305) re-evaluated 39 survivors of cooling, who had been seen at 18-36 months, again at 48 to 78 months of age. They showed a shift to worse outcomes in the older assessments.

The changes were all due to deterioration in cognitive scores : “no further CP, epilepsy, or ASD diagnoses were made, cognitive performance declined in 11 children (28.0 %; p = 0.002; Wilcoxon test)”.

These studies point out the importance of much longer follow up of these children. They are an interesting contrast to preterm infants, who, overall, tend to have improved scores on standardized tests over time. The data on behavioural issues from the Dutch study, particularly increased internalizing behaviours, was interesting to me, as I was not really aware of this as a problem after HIE, also, behavioural problems are really important to families, and they may also be amenable to interventions to improve them.

These data make me wonder about the 2 issues of mild asphyxia, and the late preterm infant. If the prevalence of adverse outcomes changes so much over time, it may be that our decisions about which babies to cool are being influenced by somewhat unreliable data. There is very little longer term outcome data from the RCTs of cooling, to 5 to 6 years and beyond, that we might be missing a measurable benefit of cooling in such subgroups.

It is vital that trials of cooling for HIE, in groups for whom it is not yet proven to be beneficial, continue to follow the participants at least until early school age, and preferably towards adolescence. Only then will we be able to develop reliable data on the risks and benefits.

It seems outcomes for extremely preterm infants are better than for children with moderate-severe asphyxia. While the disabilities doctors call “severe” improve in preterm infants, they seem to get worse for children with asphyxia. Any speculation why this is? We treat these two categories of patients differently (in terms of trials of therapy vs withholding LSI).

Pingback: Hope for HIE | Neonatal Research