There has for a long time been a thought that anemic babies with many apnoeas could benefit from a blood transfusion which would decrease their apnoeic spells. This idea has never been directly tested by an RCT. That is, a trial in which infants with apnoea were randomized to receive a transfusion or control, and the response accurately determined. I actually started such a trial when I was in San Diego, but only enrolled a tiny number of babies before leaving to return to Canada; the fellow who was involved finished at about the same time as me, and the project was sadly terminated. I admit that it is not ethical to randomize infants to a trial, with all the stress imposed, and the goodwill of parents involved, and then not have a mechanism to complete the trial, and I apologize to the parents and families involved.

The evidence we do have, therefore, comes from observational studies of various kinds and from secondary analysis of RCTs of blood transfusions at differing thresholds, in which the impacts on apnoea or on intermittent hypoxia (IH) have been recorded. Just to remind my readers, most IH is caused by apnoea, prolonged recordings of saturation are much easier than the prolonged multichannel recordings required to objectively quantify apnoea. I will use the terms interchangeably here, partly because the harms of multiple recurrent apnoea spells, are probably because of frequent desaturation leading to hypoxic injury, and resaturation, with consequent oxidative injury.

Interestingly, the 2 types of evidence give contradictory results. Observational studies tend to show a reduction in apnoea, or IH, after a transfusion, whereas RCTs don’t show a difference in apnoea, or IH, by randomized group; those with a haemoglobin maintained at a higher level do not have less apnoea/IH than those allowed to have lower Hgb.

This is an object lesson in the hazards of observational studies, especially for a condition which is very variable in severity (between patients and between days) and which eventually improves.

I actually use this example when I teach statistics and research design to fellows!

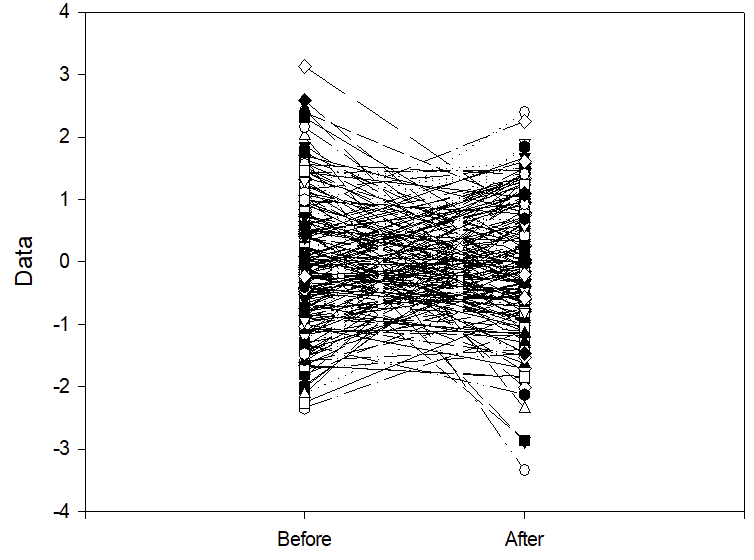

The figure below shows two columns of randomly distributed numbers which I generated, each connected by row number, with a mean of 0 and a SD of 1. If we take “0” to mean the overall average frequency of IH per hour in the sample, (it could be 4, for example), the numbers on the vertical axis are the number of Standard Deviations above and below the mean, this figure could be the number of IH per hour on day 7 and on day 14 of life of 200 preterm babies.

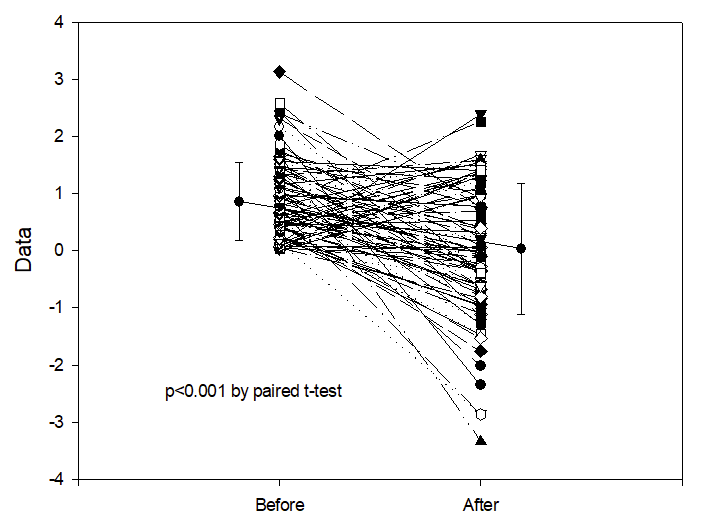

If one decides to give a treatment only to those babies who have more IH than the mean, which means you are selecting the babies in the top half of the distribution, then measure IH frequency again after the treatment. Then, even if the treatment had no effect whatsoever on IH frequency, the result you would get is shown below.

This is regression to the mean. There are very many examples of this, as a potential explanation of positive results in observational studies. Let me give you one example, of an uncontrolled study of of an apnoea treatment. Marlier L, et al. Olfactory Stimulation Prevents Apnea in Premature Newborns. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):83–8. In this study, babies having recurrent apnoea were exposed to a nice smell, lavender wafted through their incubator, and they evaluated apnoea frequency afterwards. There were fewer apnoeas when the babies had a pleasant odour in the incubator! Without a randomized control group such data are worthless. Any variable condition will tend to get better if you start treating it when it is worse than average, whether you use something effective or give a placebo.

If you tend to give transfusions to anaemic babies who are having more apnoeas, then you are immediately creating exactly this situation. If transfusions have no impact on apnoea, then an observational study will show a significant reduction in apnoea frequency following transfusion.

Also striking is what happens if you ask the question, “do babies who have the most apnoeas have the greatest benefit from transfusion?”, then plot the initial apnoea frequency against the improvement after the treatment, using the randomly generated numbers in the figure above, this gives a correlation coefficient of 0.56 and a p-value of <0.0001.

Remember, these are from entirely random numbers, after an intervention with no real impact whatsoever on apnoea frequency! All you have to do is select the most severely affected babies to treat, they will seem to improve the most.

We can see this, as a potential explanation of results which claim to show a benefit of transfusion on IH, in several studies, such as this one (Kovatis KZ, et al. Effect of Blood Transfusions on Intermittent Hypoxic Episodes in a Prospective Study of Very Low Birth Weight Infants. J Pediatr. 2020;222:65–70). In that study, they examined IH before and after blood transfusion, as well as before and after transfusion of other blood products.

IH decreased from 5.3/h to 3.6/h after blood transfusion, and was unchanged at 4.6/h before and after the small number of transfusions of other blood products.

This is exactly the result you would expect if caregivers were more likely to transfuse anaemic preterm infants when they were having a greater than average number of IH, but give plasma, platelet, or other transfusions for reasons that have nothing to do with apnoea; even if there were absolutely no effect of transfusions on apnoea incidence or IH.

I am not picking this study out as a particularly egregious example, in fact, it is a better study than most, as it at least had the non-RBC controls. You would also see something similar if there was a real impact of RBC transfusions on IH.

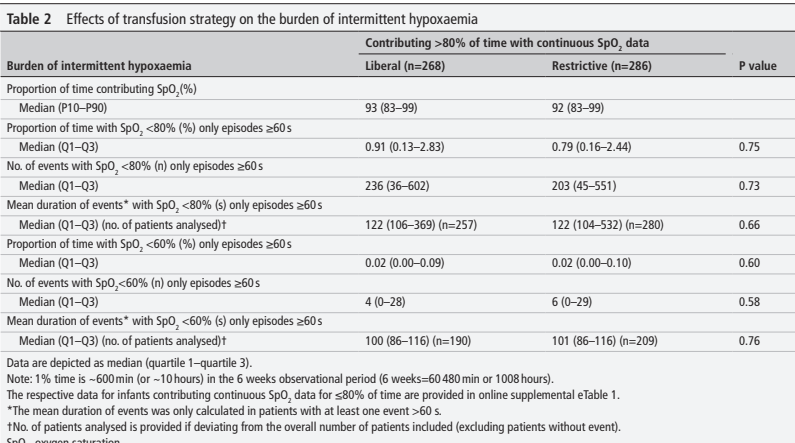

If we look at the RCTs of blood transfusions in the preterm, which have compared different transfusion thresholds, there is no apparent impact on IH or on apnoea. This includes the most recent publication, which is a secondary analysis of an RCT. (Franz AR, et al. Effects of liberal versus restrictive transfusion strategies on intermittent hypoxaemia in extremely low birthweight infants: secondary analyses of the ETTNO randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025). The ETTNO trial was a randomized comparison of differing transfusion thresholds in infants <1000g birthweight that I have already discussed, which showed no impact on the primary outcome of “survival without NDI”. There was no impact in survival or on developmental progress, as measured by the Bayley version 2 MDI, results of which were identical between groups. The transfusion thresholds were a bit complicated in ETTNO, the high threshold group had 3 different thresholds according to postnatal age in stable babies, and 3 higher thresholds in “critically ill” babies. The low transfusion group had a different matrix of 6 transfusion thresholds according to postnatal age and being stable or not. Of note, one of the indications for being considered “critically ill” were 6 or more apnoeas/day requiring nursing intervention, or IH to <60% saturation >4 times per day.

This new secondary analysis compared IH frequency and severity according to randomized group. About 50% of the babies had good enough recordings of saturation for analysis, a subgroup who seemed representative of the whole sample.

There were no differences in any index of IH between groups.

In the PINT study, one of our secondary outcomes was how many babies in the low vs high transfusion threshold transfusion groups had “apnea requiring treatment”, which was 55% in the lower Hgb group and 60% in the higher Hgb group, in other words, the small difference was in the opposite direction and not in favour of an impact of Hgb on apnoea frequency.

I don’t think there are any secondary outcome data on apnoea or IH from the TOP trial, if anyone knows of any, please let me know. A much older trial (1984) of only 56 preterm infants reported apnoea frequency among infants randomized to either have their Hgb kept above 100 g/l, or to be transfused only for clinical indications, including surgery, but also including severe apnoea not responding to theophylline as a clinical indication. There were no differences in recorded apnoea frequency despite differing Hgb concentrations. The only controlled data which show a possible impact on apnoea are from the Iowa trial, of 100 preterm infants <1300 g (Bell EF, et al. Randomized trial of liberal versus restrictive guidelines for red blood cell transfusion in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1685–91) which had more apnoea spells in the lower threshold group, and more apnoea requiring nursing intervention, 0.4/day compared to 0.2/day. In that trial, infants were allowed to receive a transfusion, even if they were in the low threshold group, if they had multiple apnoeas, which is a possible confounder in analysing the meaning of that result.

I looked for systematic reviews of transfusion in the preterm to see if any had analysed the impact on apnoea, and was unable to find any other reliable data, but read my next post to see what I did find.

My take home message is that there are few reliable data to show that apnoea or IH is more frequent in infants with lower Hgb, nor any reliable evidence that RBC transfusion reduces apnoea or IH in the preterm.

If you transfuse babies who are having more apnoea, or more IH, than average they will usually have a reduction in their episodes.

But :

If you don’t transfuse babies who are having more apnoea, or more IH, than average they will usually have a reduction in their episodes.

The only way to resolve the issue would be to do a trial similar to the one that I started years ago. Enrol anaemic infants with apnoea or IH, randomize them to transfusion or control and obtain objective recordings of their responses. I have a strong feeling, based on my evaluation of the currently available data, that both groups will show a reduction in apnoea/IH, and that there would be little or no difference between the two groups.

Pingback: Lactoferrin supplementation does not prevent late-onset sepsis in the preterm… or is it more complicated that that? | Neonatal Research