Current guidelines support the use of therapeutic hypothermia for term infants with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Both the Canadian and the US guidelines include infants born at 35 weeks gestation. However, the data supporting efficacy for those late preterm infants, is extremely limited, and less mature infants were excluded from all the major trials. The discussion section of this new publication reveals that the 2 RCTs which included babies of 35 weeks GA had a total n of 7.

This lack of reliable information for a group of infants who are referred with acute encephalopathy led to the performance of an RCT by the NICHD network. Faix RG, et al. Whole-Body Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy in Preterm Infants 33 to 35 Weeks’ Gestation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(4):396-406. They enrolled 168 infants born at 33 to 35 weeks gestation, with moderate to severe encephalopathy, including a depressed level of consciousness, they did not require EEG (or aEEG). The intervention group were cooled to a standard 33.50 for 72 hours, starting within 6 hours of birth, and the controls were maintained around 370.

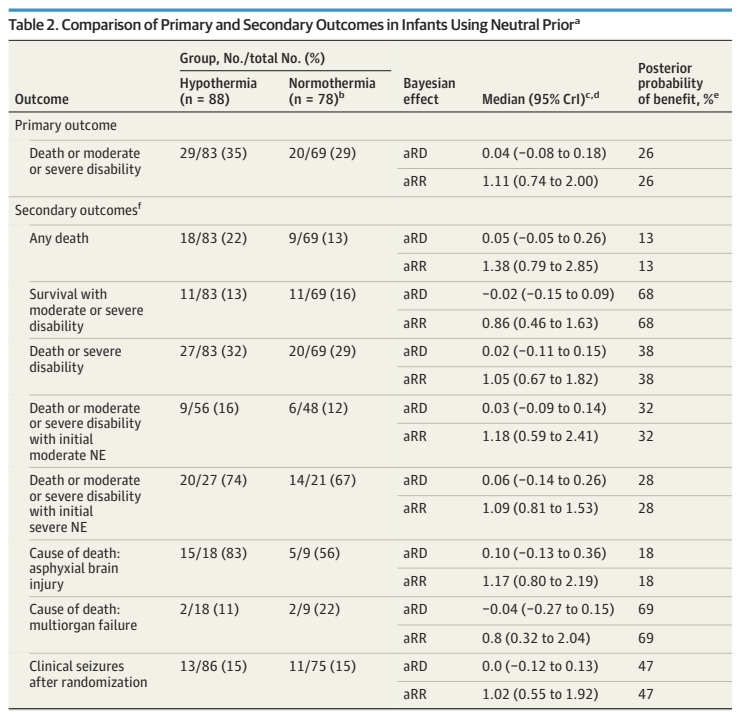

The primary outcome was death or disability, with disability defined as severe : Bayley III cognitive score <70, GMFCS level 3-5, blindness, or deafness despite amplification; or moderate : cognitive score 70-84 or, GMFCS level 2, treated seizure disorder, or hearing loss requiring amplification. Primary analysis was a Bayesian approach, with the prior assumption being no effect of the intervention.

As you can see there was no indication of any benefit. Death was more frequent in the hypothermia group, and outcomes among survivors were just about identical, a slightly proportion with severe disability in the hypothermia group (and interestingly, almost no survivors with moderate disability, in either group, 2 vs 0). The Bayesian analysis shows there is very low probability of benefit of cooling in this population. Also, there were many of the cooled babies who overshot their target, 32 of them had a temperature recorded under 320 during the first hour of intervention.

Interestingly, the way this is presented in the table is that there is only a 13% chance of benefit on mortality with cooling; in the discussion this is stated as an 87% probability of harm from the treatment, which gives a zero chance that the treatments are equivalent! Maybe it’s just my poor understanding of Bayesian analysis. Within Bayesian analysis there are ways of evaluating different magnitudes of treatment effect, which is something that I think we should consider for the future, rather than presenting data as if the only 2 possibilities are that the outcomes are either better or worse, it would perhaps be more helpful to calculate the probabilities of a particular, clinically important impact, and the probability that mortality is about the same, using whatever limits are considered appropriate. I guess, if the probability of benefit had been about 50%, then you could say the treatments are equivalent?

On the other hand, for this intervention, as there is very low probability that cooling is beneficial, we should not cool the late preterm infant with encephalopathy. For babies at 35 weeks, these data are much stronger than those previously available, and 35 week GA infants should probably not be offered therapeutic hypothermia, and should be excluded from the next version of any guidelines.

Thank you for this thoughtful commentary. This paper does raise a lot of doubt, especially since the pendulum had swung down to 34 weeks GA at a lot of academic centers. This study had about 25 babies between 35w0d and 35w6d out of the 88 total and I wonder if that number is enough to draw a strong conclusion one way or other. Regardless, for babies between 35-36w0d, my instinct will be to have a much higher threshold like ( near 36 weeks or concerns on EEG or both to initiate cooling) and have a low threshold to stop if concerns for instability are noted.

Pingback: Therapeutic Hypothermia at 35 weeks | Neonatal Research