I have written frequently about my concerns with “NDI” as an important measure of neonatal outcomes, indeed, it seems to be often thought of as if it were the only important measure. It has very often been included as part of a composite outcome measure “death or NDI”.

So why am I disturbed about the use of NDI as a primary outcome measure? NDI is itself already a composite measurement, including some indicator of delayed development (most commonly one of the various iterations of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development), some severity of motor disorder expected to be permanent, i.e. Cerebral Palsy, some severity of hearing loss, and some severity of visual impairment. It was a composite invented by neonatologists and follow up specialists as a way of trying to quantify the impacts of adverse cerebral impacts of prematurity. There are many problems with this, both in the actual importance of each component of NDI, and also in the permanence of the finding. For example, most infants with low scores on developmental screening tests at 2 years do not have intellectual impairment at follow up. In the follow up of the CAP trial, for example, only 18% of babies who had a low Bayley score at 18 months (version 2 MDI <70) actually had a low IQ at 5 years (WPSII <70). This is unlike CP, for which a diagnosis at 2 years is very accurate (not 100%, but appears to be about 95% PPV) as a predictor of long term motor dysfunction, but the severity of the problem can vary, especially after a diagnosis at 2 to 3 years, where about 1/3 of infants will change their classification on the GMFCS, either to a higher or a lower score. Visual and auditory impairments seem to be more permanent and invariable, but are a much smaller part of the NDI.

And, of course, combining NDI with death as part of a composite outcome implies that they are equally important, and means that an intervention which decreases death may not be found to be significant is there is an increase in low BSID scores in the survivors (for example).

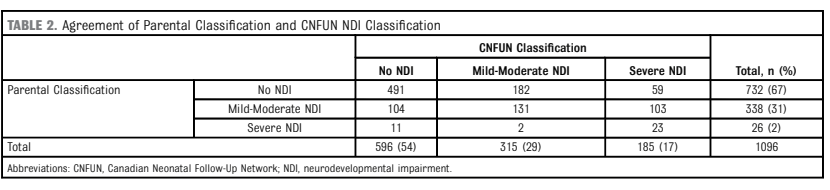

Do parents of babies who are labelled as having NDI think that their infants are impaired? That is the question asked in a new publication from the follow up centres across Canada (Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network, CNFUN). Richter LL, et al. Parental and Medical Classification of Neurodevelopment in Children Born Preterm. Pediatrics. 2025. Over 1000 very preterm infants are involved in the study, and their parents were asked if they thought that their child had a developmental impairment when they attended a follow-up clinic appointment, but before they completed the standardised evaluation. They then had their evaluation and were classified as having no NDI or :

“to have a mild-moderate NDI if they had any 1 or more of the following: CP with GMFCS 1 or 2; Bayley-III motor, cognitive, or language composite scores 70 to 84; hearing loss without requirement for hearing devices or unilateral visual impairment. A child was considered to have a severe NDI if they had any 1 or more of the following: CP with GMFCS 3, 4, or 5; Bayley-III motor, cognitive or language composite scores <70; hearing aid or cochlear implant; or bilateral visual impairment.”

As this table shows, there was poor agreement between what the parents thought, and what the standardised evaluation stated. Most of the disagreements were parents considering their infants to not be impaired, or to be less impaired than the standard classification. There were 185 infants with “severe NDI” according to the definition above, only 23 parents thought their child was severely impaired, in contrast, among the 596 with no NDI, there were 11 parents who found their child to have severe impairment, and 104 thought they had mild-moderate impairment.

Some of the details of the analyses are quite interesting, for example, the small number of infants with serious CP, GMFCS 4 or 5, were mostly considered to have moderate or severe impairment by parents. The cognitive scores of infants who agreed that their infant, with CNFUN defined severe NDI, had at least moderate impairment were lower (median 70) than those who disagreed (median 80).

Many problems faced by families with ex-preterm infants are not captured by “NDI”. This is reflected, I think, by those parents who thought their child was impaired despite not satisfying CNFUN definitions, such infants were much more likely to be using technology at home, and more likely to have been referred for occupational therapy, or to see a psychologist or other therapist. Needing re-hospitalisation also made parent more likely to agree that their infant had an impairment.

Because we haven’t measured some of the things that impact families, such as behavioural disturbances, feeding problems, and sleep disruption, we really don’t know if they are affected by any of our NICU interventions. It wouldn’t surprise me if some interventions, ranging from postnatal steroids to skin-to-skin care or light cycling, might have major impacts on those outcomes. We just don’t know.

What should we do about findings such as these newly published data, and others from the Parents’ Voices project? Defining a single ‘yes or no’ outcome variable is the old-fashioned way of designing research and determining the benefit of an intervention. There are much better ways of comparing outcomes between groups, ways which can take into account the variety of outcomes, and the preferences of parents. It takes some extra work to define the kind of ordinal outcomes which reflect the values of parents and the relative importance of each component, but that is hugely preferable to using composite outcomes which implicitly value each component as being equivalent. Being dead, having a Bayley Cognitive composite of 69, having severe visual loss all qualify as “dead or severe NDI”, but the implications are enormously different.

In the future outcomes we measure should focus on how infants function, and should recognize that the answer to the question “how is your child doing?” is not a dichotomous choice.

Pingback: Horizons, ND Impairment, Parent Personalization – The Neonatal Womb Warriors