An important multi-centre observational study examines how many newborn infants, term or late-preterm are receiving antibiotics, for how long, and the responses to negative cultures. Centres from Europe, Australia and North America are represented. Data collection differs between the participants which are all regional networks (or in the case of Norway, national), but all provided data on babies who received antibiotics for any reason within the first week of life.

The first publication from the study (Giannoni E, et al. Analysis of Antibiotic Exposure and Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis in Europe, North America, and Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2243691) showed that 2.86% of the babies in the networks (total births over 750,000) received antibiotics, but the variability was enormous between networks, from 1.18% to over 12%.

The overall incidence of culture positive sepsis was less than 0.05%, if the coagulase negative staph are eliminated (they were not automatically considered to be contaminants in this study, but I think it is very rare that EOS in term and late preterm infants is really caused by CoNS) the incidence was 0.041%.

One thing I really appreciated in this publication is the openness of the investigators to identify themselves. As you can see below, the centre with the highest exposure of babies to antibiotics was Perth. As you can also see, from panel B, they, and Rhode Island, are the sites with the shortest duration of treatment of culture negative babies. As you can also see, panel D, Perth dramatically reduced antibiotic exposure between 2014 to 2018.

Figure 3 in that publication shows a vague correlation between actual sepsis incidence and antibiotic use. In the supplement there is a version without CoNS

I find it hard to believe that individual decision making about sepsis evaluations and antibiotic treatment are affected by a difference in true EOS rate between just over 1 per 1000 compared to 0.3 per 1000. But, perhaps, the local choice of which guidelines to follow is affected by sepsis rates?

In terms of the consequences of sepsis, EOS mortality was very low, at 3.2% of the true EOS cases, or 12 deaths among 750,000 babies. As you can see from the figures, Stockholm county has an average incidence of EOS, but consistently has the lowest rate of antibiotic treatment. They do this, it appears, by not using the Kaiser Permanente sepsis calculator. That calculator has reduced antibiotic use in centres where it has been introduced, but the lowest antibiotic use reported after introduction of the sepsis calculator is 3%. In Stockholm the rate is less than half of that. How do they do it, without an increase in sepsis mortality? As far as I can tell, there are no published guidelines in Sweden regarding when to screen and/or treat the term and late preterm infant for sepsis. I downloaded and translated the national recommendations, but they only discuss the antibiotics available, the importance of blood cultures, a statement that culture negative sepsis is a possibility, and a vague discussion of epidemiology. This is the automated translation (Microsoft Word) of the section about screening and diagnosis:

Underdiagnosis of severe neonatal infection can quickly lead to a worsening situation of septic shock and even death, while overdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary antibiotic use. Fatigue, poor skin color, episodes of apnea, and bradycardia are common symptoms of sepsis.

Using hands, eyes, ears and stethoscopes to examine the patient and interpret these symptoms is and remains the basis of all diagnostics. In addition to this, the doctor has a number of diagnostic methods available, each with its different strengths and weaknesses (Table III). There is currently no method that has optimal speed, sensitivity and specificity. CRP is the most commonly used diagnostic test.

Another recent publication of national data from Sweden, which includes over 1 million babies and extends until 2020, shows a continuing low frequency of antibiotic exposure, with a decreasing incidence of EOS. Again, in that publication there is no mention of any general guidelines for when to screen and treat for suspected sepsis.

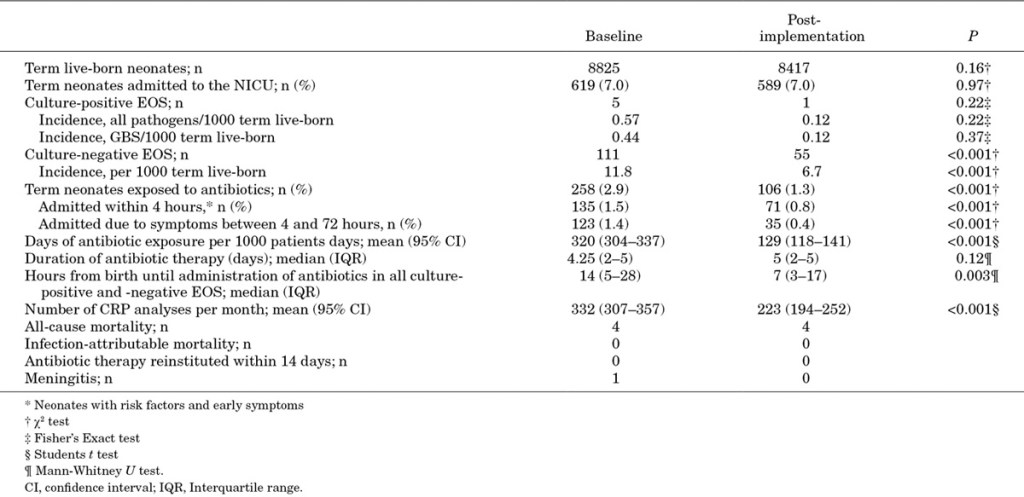

Other jurisdictions have adopted the “Serial Physical Examination” approach, but the details of such an approach vary, it generally requires hourly structured physical examination by a nurse, following a written and agreed protocol, of at-risk infants. This article from Stavanger, Norway, for example, (Vatne A, et al. Reduced Antibiotic Exposure by Serial Physical Examinations in Term Neonates at Risk of Early-onset Sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(5):438-43) is rather vague on which infants qualified as “at-risk”; it seems to be any infants born after chorioamnionitis (undefined) or with a previous sibling with GBS, and “neonates who during the first 72 hours of life developed clinical symptoms indicating a possible sepsis”. All such babies were admitted to the NICU for an hourly structured physical exam.

we accepted mild symptoms (heart rate >160/min, grunting or respiratory rate >60/min, poor feeding and decreased activity) of <2–4 hours duration. We only started antibiotics if these mild symptoms persisted (>2–4 hours) despite corrective actions, if additional alarming symptoms occurred (Table 1) or if the neonate became clinically ill as judged by the attending neonatologist.

This is the Table 1 referred to:

That study was limited to babies of at least 37 weeks, and was able to decrease antibiotic exposure from about 3% to about 1.3%; the incidence of “culture-negative sepsis” also declined dramatically, but remained, supposedly, 50 times more frequent than culture-positive sepsis.

One factor which has probably reduced the incidence of “culture-negative sepsis” is the reduction in CRP measurements! As you will see in part 2, many babies receive prolonged antibiotics to treat their CRPs.

Antibiotic treatment rates much lower than those which follow use of the current EOS calculators can be achieved without any increase in sepsis mortality. Of course the consequences of EOS are not just mortality, untreated, or late-treated EOS may lead to more severe acute illness and long term disability. Such outcomes are very difficult to capture in studies such as these, all-cause mortality is one outcome to be followed, in case babies present with severe illness not recognized as being sepsis, and, in these studies, lower antibiotic use is not associated with increased all-cause mortality.

Decreasing antibiotic exposure in uninfected infants is an issue which is important individually, as it leads to major disturbances of the intestinal microbiome, which are very prolonged, pain caused by IV access, cost, interference with parent-infant interaction, vulnerable child syndrome, and perhaps long term health impacts such as obesity, allergic predisposition, asthma, diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, celiac and inflammatory bowel disease. To the health care system as a whole, the exposure of a significant proportion of the population to antibiotics must contribute to antibiotic resistance.

excellent post

trying to finish some stuff here, but getting side tracked by my husband’s blog!

Annie

excellent post, there is continue evidence that we abuse of antibiotics and the consequences that this will have in the present ( resistence) and in the future ( co-morbilities)