In 2022 we published an article addressing the question in the title. As part of the Parents’ Voices Project, we questioned families of very preterm infants at follow up about their experiences prior to, during, and after the NICU. 98% of families attending responded, the extremely high response rate being partly because they were given multiple different potential ways of participating (on-line, on paper, in person); about 30% of respondents were fathers. We published a qualitative analysis of the responses to an open-ended question “knowing what you know now, is there anything that you would have done differently?” (Thivierge E, et al. Guilt and Regret Experienced by Parents of Children Born Extremely Preterm. J Pediatr. 2022;257:113268). None of the parents reported regret about life-and-death decisions that they participated in. Of course this was a “biased” sample, of only parents of surviving babies. Many parents did express regret, but it was usually because they regretted not looking after themselves during the NICU period, or they felt guilty about the preterm delivery and regretted the things they had done that they believed had triggered that delivery.

Of importance there was no difference in regret or guilt between parents whose children were considered to have “impairments”, using standard definitions, and those without impairments. Also, as we have also shown, parents often don’t agree with the medical classification of their infant as being impaired or not (new publication to come soon in ‘Pediatrics’); and, using parents own classification of their infants as having challenges or not, didn’t change the fact that they were not more likely to express guilt or regret if they thought their child had limitations.

A new publication from 2 US centres (in Portland OR and Newark NJ) has used a published scale to survey mothers of infants who delivered between 22 and <26 weeks GA, from 2004 to 2019. 56% of them were contacted and 54% participated. Of the respondents, 137 of them stated that they had chosen active intensive care, 43 comfort care, and 23 “other”. Unfortunately, with the very long delay between delivery and being surveyed for some mothers, the authors found some discrepancies between what was reported in the charts, what was actually done, survival, and the mothers’ reports of their decisions. They used a published scale to evaluate decision regret.

The scale is constructed from responses to 5 statements, each on a Likert scale of 1= ‘strongly agree’, 2= ‘agree’ etc to 5= ‘strongly disagree’. Here are the 5 statements:

1) It was the right decision.

2) I regret the choice that was made.

3) I would go for the same choice if I had to do it all over again.

4) The choice did me a lot of harm.

5) The decision was a wise one

As you can see, statements 2 and 4 were expressed as negatives, in order to account for some people who tend to just agree to everything, so the Likert scores for those items are reversed.

The responses are then averaged, 1 is subtracted, then the result multiplied by 25. If someone answered ‘strongly agree’ to all except one, and ‘agree’ to one of the statements, they would score 5; and if someone responded ‘agree’ to all the statements they would score 25. What I don’t understand, in the way these are interpreted in this publication, is that a score of 5 to 25 is considered an “elevated decision regret score”; which is bizarre. If I am comfortable with the decisions that were made, and I tick agree with every statement, rather than strongly agree, the authors report that as elevated decision regret, whereas I think it is the opposite, showing very little decision regret.

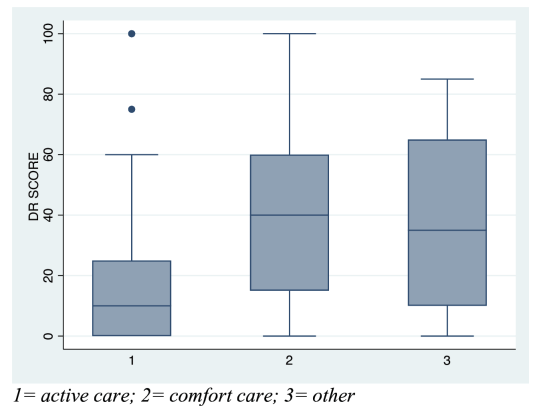

There were differences between mothers who reported an active care decision to those remembering other decisions. As you can see here, the 75%le for the score in the ‘active care’ group shows very little decision regret, with substantially more showing regret among the other 2 groups.

Also, one of the determinants of a higher decision regret score was that the infant died; either after comfort care, or in the DR, NICU, or at home, after active care, whatever the decision was made.

As the authors note, there is little other direct research of decisional regret in neonatology. Guertzen et al have published 2 studies, the first, from 2017, (Geurtzen R, et al. Prenatal (non)treatment decisions in extreme prematurity: evaluation of Decisional Conflict and Regret among parents. J Perinatol. 2017;37(9):999-1002) with unfortunately very low response rates (27%), the sample was restricted to parents who actually delivered at 24 weeks. At the time that study was done, optional care at 24 weeks had recently been recommended by the Dutch guidelines (previously being limited to 25 weeks and above) the low response rate and total n of 61, meant that there were only 5 who opted for comfort care among the respondents. Although the authors did show low decision regret scores (using the same scale as the new publication), the small numbers in some groups make interpretation difficult. Decision regret was very low among parents of survivors, and higher among parents of babies that died despite active care, but the scores were still very low (median 7.5). Among the 5 who opted for comfort care decision regret was higher, but the tiny numbers and low response rate make it impossible to extrapolate, it is possible that those with regret, or those who opted for comfort care were less likely to respond. The second publication from the group from 2021 (Geurtzen R, et al. Decision-making in imminent extreme premature births: perceived shared decision-making, parental decisional conflict and decision regret. J Perinatol. 2021;41(9):2201-7), studied parents who underwent counselling between 23 and <25 weeks, they were questioned 1 month later. There were only 20 respondents to this part of the study, most of whom actually delivered after 25 weeks. There was little decision regret.

Another study I found included some newborns, as well as other infants under 1 year of age with “neurological conditions” who had a “goals of care” discussion, defined as being a discussion about continuing life-sustaining interventions or instituting long-term medical technology. (Barlet MH, et al. Decisional Satisfaction, Regret, and Conflict Among Parents of Infants with Neurologic Conditions. J Pediatr. 2022). It is a mixed bag of patients, whose parents were questioned about decisional regret one week after discharge. The study included just over 60 parents, They used the same scale as in those other studies, and, in addition, a scale of decisional satisfaction and another designed to measure uncertainty in decision making, which they refer to as “decisional conflict”. They showed fairly frequent decisional conflict (perhaps not the best term as many answers just show a lack of certainty rather tha conflict) but very little decisional regret, and most parents were satisfied with their decisions. I don’t see an analysis of whether there is any difference in scores depending on the outcomes, survival, death or impairment.

I have had a brief scan through other studies about decision regret, including a systematic review from 2016, which found 59 articles, covering many different aspects of medical decision making, from individuals having cosmetic surgery, through parents making decisions about hypospadias surgery, to surrogates who made decisions about life-sustaining measures in the adult ICU. In general, looking at the more critical decisions, the majority of respondents have little regret regarding their decisions, whatever the decision, and whatever the outcome.

When patients survive without long term consequences, there is very little decision regret (as you might expect). When the patient dies, those who made decisions for limitation of active care seem more likely to experience regret than those who decided for active intervention. The feeling that “at least we tried” seems to lead to less regret than “what if we had tried?) And what about those whose loved one survives after a decision to continue active care, but has major long-term consequences? Among families who have made such decisions, regret still seems to be quite uncommon.

In terms of my personal history, I have spoken on occasion about the decisions we made about starting intensive care for my daughter, born at 24 weeks and 3 days in May 2005, and about the crisis a couple of weeks later when she was critically ill and comatose with septic shock. We came very close, within minutes, of redirecting care, but with the support of my mentor Neil Finer, and following some minimal signs of improvement thanks to the excellent care of the NICU team, we decided to continue full intensive care. I am very proud to tell you that Violette has just started in the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at the Université de Montréal! Here she is modelling her first set of scrubs.

We obviously haven’t the slightest hint of regret for our decisions, but I am trying to imagine how I would have felt about our decision now, 19 years later, if she had died. I honestly think that if we had continued with our decision for comfort care, and she had died, I would be heart-broken, but probably not feeling regret for the decision. I would not, of course, know how she might have ended up, and would, I imagine, be comfortable that we had made the right decision for the right reasons. If she had died despite changing our minds, and continuing intensive care, then I would still probably be comfortable that at least we had given her a chance. I am less sure how I would feel about the other possibilities, such as her surviving, but with major limitations. Most parents do not regret decisions that they made for their children, even if they have serious challenges, and most parents with challenged kids report both good and bad impacts of their preterm baby on their family. (Milette AA, et al. Parental perspectives of outcomes following very preterm birth: Seeing the good, not just the bad. Acta Paediatr. 2022;112(3):398-408). Indeed my lit review seems to confirm that parents of children living with even very severe impairments rarely regret intensive care or life and death decisions that they made.

Do we sometimes worry that parents who decide to continue active intensive care in life-threatening situations might regret such decisions if their infant survives with major limitations? If so, that worry seems to be unfounded. Regret appears to be more common (even if still a minority) among parents who decide for comfort care.

So great to see that Violette is starting nursing school. Best of luck to her!

Good to see this work continue and to dive more deeply into the concept of decisional regret. Thank you for also sharing your personal journey – and the lovely picture of Violette in her brand new scrubs. Personally I am so very proud that she chose nursing (or perhaps it chose her)! Will never forget your time in Washington with us that May – and the purple ribbon we tied around the podium with hope for Violette, and you and Annnie.

i remember when Dr Annie Janvier asked these same ethical probing questions about viability and risks of handicaps…..she was then a new paediatrician at RVH ..i loved you both Thank you for the strength and courage to tell your story…i was there, and now greatly honoured Violette is becoming a BSC NURSE just like me in 1982