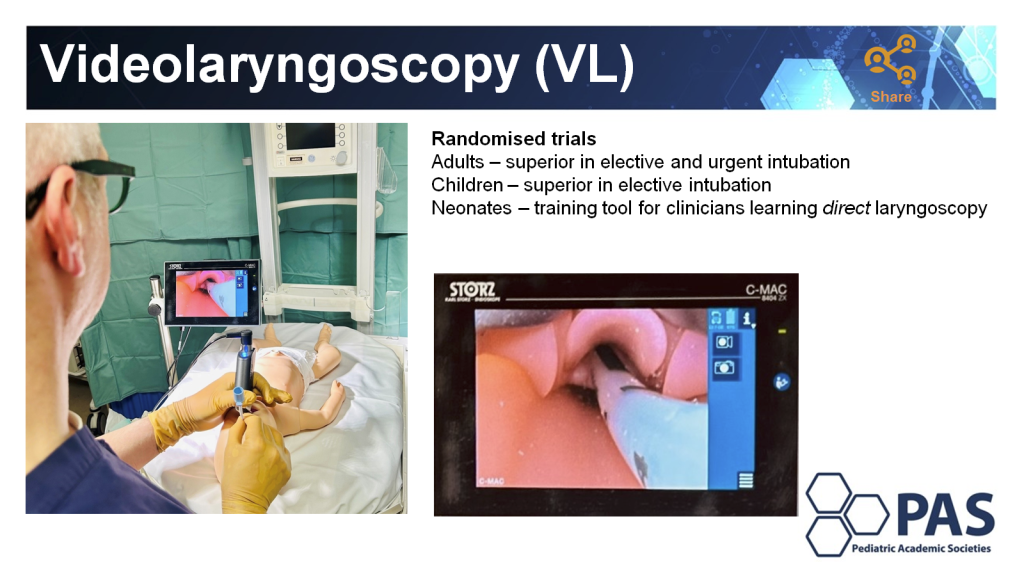

I have been increasingly using video laryngoscopy in my practice, both when I myself perform the intubation, and when I am supervising a resident or other trainee. I usually ask them to use a VL when it is a nurse practitioner or RT that is about to intubate also.

It already seemed to me that the evidence was very supportive, with lower failure rates with VL than standard laryngoscopes, and I really appreciate the ability to see what someone else is doing when training them. A recent large RCT in adults with over 8000 procedures showed that the failure of the first intubation attempt was about 7.6% with direct laryngoscopy and only 1.7% with a video device. Intubation failure (needing more than 3 attempts or switching to a different device) was 4% with standard technique, and only 0.26% with the video. Ruetzler K, et al. Video Laryngoscopy vs Direct Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation in the Operating Room: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;331(15):1279-86.

I wish we could have success rates that high; multiple intubation attempts lead to local trauma, pain, increased physiologic deterioration including spikes in intracranial pressure and are associated with increased IVH. In marked contrast to the above study in adults, a recent single centre randomised study of video versus direct laryngoscopy for nasotracheal intubation in the newborn (n=89) had desperately poor rates of intubation on the first attempt: 49% success on the first attempt with the video, and 44% with direct laryngoscopy. Tippmann S, et al. Video versus direct laryngoscopy to improve the success rate of nasotracheal intubations in the neonatal intensive care setting: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2023;7(1). Infants received fentanyl and midazolam, some of them received vecuronium “if intubation conditions were considered inadequate after analgesia and sedation”, I have no idea how you can determine this prior to laryngoscopy. Most of the intubation first attempts were by trainees (60%), and the babies were intubated either in the delivery room or the NICU, most were preterm. Although I said first intubation success was “desperately poor”, such results are similar to many other studies which also have very poor success on 1st attempt.

Another multicentre study, performed by anaesthetists in several countries, after induction of anaesthesia, muscle-relaxed newborn infants up to 52 weeks PMA in the Operating Room were randomized to standard or video laryngoscopy for their intubation. (Riva T, et al. Direct versus video laryngoscopy with standard blades for neonatal and infant tracheal intubation with supplemental oxygen: a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(2):101-11). First attempt success was 89% with the VideoLaryngoscope (VL) and 79% with the standard blade. These were largely full term infants with a mean PMA of 44 weeks.

What can we do to improve these poor success rates? Well, in addition to the RCTs, there is an ongoing multicentre quality evaluation initiative Near4Neos that has shown that you are more likely to be successful if you use muscle relaxant, and if you use a VL. But overall, in those database studies, success of the first attempt was still very low. With muscle relaxant 56% 1st attempt success, vs 33% with sedation alone, and 58% with the VL, compared to 47% with direct laryngoscopy.

We have also shown, from our centre, that restricting intubations of the highest risk babies to individuals with proven competence improves success rates. Gariépy-Assal L, et al. A tiny baby intubation team improves endotracheal intubation success rate but decreases residents’ training opportunities. J Perinatol. 2022;43(2):215-9. We increased the first attempt success rate from 44% to 59% when junior residents were only allowed to intubate babies <29 weeks after proving competence in larger babies. We also have well organized simulation training, direct supervision by more senior staff, a premedication protocol which is always followed in the NICU and which includes muscle relaxation.

Which brings me to the new trial, presented in Toronto at the 2024 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting, and published the same day in the NEJM. Geraghty LE, et al. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Urgent Intubation of Newborn Infants. N Engl J Med. 2024. This single-centre RCT from Colm O’Donnell’s unit in Dublin randomised just over 200 babies, in the DR or in the NICU, who required urgent intubation. It therefore included preterm and term infants, and babies in the NICU routinely received premedication, which included a muscle relaxant.

The results showed a dramatic difference.

The paediatric residents success rate went from 40% to 70%, neonatal fellows from 53 to 77%. There were very few performed by staff neonatologists, even though the slide from the presentation in Toronto shows Dr O’Donnell’s ear as he is intubating with a VL:

As you can see from the next figure the advantages applied to small and preterm babies as well as the overall group, in the DR and in the NICU.

The successful first attempts took about 10 seconds longer with the VL (60 vs 50 seconds), but that did not increase the number of babies with major desaturation or bradycardia.

One other new RCT of neonatal intubation compared the use of stylets to no stylet, in contrast to the only previous RCT that I am aware of, which showed a very small difference in success or duration of intubation attempts (from the group in Melbourne, and including Dr O’Donnell as an author), this new trial showed a greater first attempt success with the stylet in intubations in a surgical NICU compared to no stylet. Success of 1st attempt was an impressive 81% with and 73% without stylet among 200 newborn infants, with a mean GA of 36 weeks. (Solanki S, et al. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the rate of successful neonatal endotracheal intubation performed with a stylet versus without a stylet. Paediatr Anaesth. 2024;34(5):448-53).

Of note, some of my colleagues performed a fascinating trial among paediatric trainees, Michael Assaad and Ahmed Moussa are 2 of my colleagues in Sainte Justine, and Ewa Gizicki was one of our fellows, the other authors of this trial are colleagues from across Quebec. They randomized residents about to intubate a baby to a 10 minute training session (if there was time depending on baby’s condition, of course), which consisted either of a 10 minute video, or “Just In Time” training, which was a 30 second video accompanied by practice on a mannequin, supervised by a staff who used scripted feedback depending on the difficulties experienced. Gizicki E, et al. Just-in-time Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation Simulation Training: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr. 2023:113576. First attempt success rate was improved in the JIT group 54% compared to 41%. Rethinking exactly how we train and supervise residents for this important skill has been a focus of my 2 colleagues for a while, this approach requires a lot of the staff supervising, but it seems to work.

I think the accumulation of evidence and this new RCT makes it clear that Video-Laryngoscopy should be considered the standard of care of neonatal endotracheal intubation. It has universally been shown to reduce failure of the 1st intubation attempt, and even though the 1st attempt may be slightly longer, the overall duration of laryngoscopy is much shorter as you are more likely to only do it once!

Optimal Endotracheal Intubation Procedures:

- Ensure that the appropriate person is doing the procedure, someone who has been well-trained, with the use of simulation before practising on babies.

- High risk intubations should only be performed by an individual with proven competence. Intubating a 500 gram infant is not the time for a junior resident to “have a try”.

- If at all possible, the baby should be premedicated, using an analgesic with a rapid onset (not morphine), and a muscle relaxant with rapid onset and short duration of action.

- Oxygen should be administered during the procedure, preferably by high-flow nasal cannulae.

- Video-laryngoscopy should be used for all neonatal intubations, both in the DR and in the NICU (note to self, we need to get them available for the transport team also).

- Senior supervision of trainees is essential, and is also facilitated by Video-Laryngoscopy.

Endotracheal intubation is the most traumatic procedure that we perform frequently in the NICU, multiple intubation attempts harm our babies, and we should do everything possible to reduce their number.

Well done review. Discussion is needed about the ELBW and the use of the “00” blade. In my experience, even the 00 is too wide in the micropremie.

That is true David, the previous version of the Storz had a blade that is too big for the tiniest babies. There are new devices available, and I believe that Storz have redesigned the small blade. The newer devices may not have FDA approval, however, so there may be a delay in implementing this for the babies where first intubation success is the most important.

Great review. Agree with you that VL should be standard of care based on the accumulated evidence. I still wonder why first attempt success rates is lower in newborns even with VL ( especially in delivery room)? and What do you think Geraghty et al did differently to improve first attempt success rate compared to previous trials and observational studies that used video laryngoscopy? Are the VL designs have changed for better, are we more used to or more accepting?

I’m not sure why they had such a good success rate, but it looks like their residents had quite a lot of experience, and they routinely use premedication in the NICU, where the 1st attempt success rates were very high. In the DR 1st attempt success was about 65% with the VL and 35% with direct.

Training with simulation and immediate preintubation coaching can improve those success rates.

Great review. I believe simulation training under supervision for trainees is vital. They need to learn landmarks to look for when inserting a laryngoscope blade either VL or a casual. No doubt VL remains more effective and beneficial.

Dear Keith, I absolutely enjoy your posts as a neonatology trainee during my night shifts and it keeps me easily updated. Challeging is the transformation of new information to my older collagues since there is often a rule of never change a winning team in the field of medicine.

Anyway, using muscle relaxant in even ELBW is a new subject to me just for intubation – what kind of relaxant do you use frequenctly? How do you handle a can’t ventilate can’t intubate situation after applying the relaxant? Looking forward to your answer.

I think, to be brutal, if someone can’t ventilate an apnoeic infant with a face mask they are in the wrong profession! It is something we do every day in the DR for resuscitation.

Muscle relaxation facilitates intubation for the provider and for the baby, it makes it quicker, more likely to be successful on the first attempt, and associated with less physiologic disturbance. It should be accompanied by analgesia. For both analgesia and muscle relaxation you need an agent with a rapid onset of action, for muscle relaxation it is preferable to use an agent with short duration of action, and for analgesia an agent that has little, or brief, depression of respiratory drive.

The appropriate muscle relaxants are therefore succinylcholine and mivacurium. Cis-atracurium is a possibility, but has been little studied, so I am not sure how long it lasts in a preterm infant.

I have used Succinylcholine now in several thousand intubations, and never run into a problem, this includes hundreds in very tiny infants down to 400g. Infants with abnormal airways are a special group that need expert intervention, with the assistance of ENT or sub-specialist anaesthetists.

Thank you for your honest and rapid reply which is very well appreciated.

I may be biased from working a couple of years in the field of anesthesia where you should not using muscle relaxant in case of uncertain ventilation.

So I might discuss with my collagues to give the named medications a try. It is not very common to use muscle relaxants (either of both groups) for intubation where I am working in the neonatology department.

Any recommandation for the dosage of succinylcholine?

Highly regards.

We use 2 mg/kg of succinylcholine. Duration of action is short enough that we always have a second dose prepared, in case the baby starts to move before the intubation has been performed. We don’t often have to give it though, as most are intubated on the first attempt with videolaryngoscopy and careful selection of the operator.