Is it possible that giving artificial formula to babies will prevent 90% of the deaths of very preterm babies, compared to using donor human milk? (Chehrazi M, et al. Outcomes in very preterm infants receiving an exclusive human milk diet, or their own mother’s milk supplemented with preterm formula. Early Hum Dev. 2023;187).

The results of this study are nonsensical. If you were to accept the results of this study, then donor breast milk is the most dangerous thing we can give to preterm infants, and the more immature you are, the more dangerous it is. The study implies that all preterm infants should receive at least a bit of artificial formula, that way survival would be dramatically better!

This publication is based on data collected from the NNRD in the UK, a database of clinical information; they compared outcomes from babies under 32 weeks gestation who received only mother’s breast milk (MBM) and artificial formula, to those who only received MBM and pasteurized donor milk. There were initially 36,000 infants in the database, 8,140 of them were selected for this study based on the feeds they received, which were recorded every day. The first group received some MBM, and in addition received solely artificial formula and never received donor human milk (7,133 of them); the comparison group only received pasteurized donor milk (n=1,007) when they needed a supplement and never received bovine-milk-based fortifier (or artificial formula).

All cause mortality was 29% in the donor milk group and 1.9% in the artificial formula group.

What?

There is something seriously wrong with these data.

In Canada in the same years 2017 to 2021, among all admissions to the CNN NICUs of less than 32 weeks, mortality was between 8.3 and 7.4%. The selection of cases for this study has somehow managed to derive a group with dramatically higher, and another with dramatically lower, mortality than the CNN.

The babies who were selected to be in the human milk group apparently never received any fortifier. Which is very strange. Do large numbers of UK neonatal units treat babies of 22 to 28 weeks gestation without ever fortifying their feeds?

According to the results section, there were also 2,123 babies who never received either formula or donor breast milk, only getting MBM, and there were 9,965 who got a combination of MBM, donor milk and formula. Which leaves another 17,845 babies, who received what? The only group left seems to be exclusive formula feeding, According to this study, almost 50% of very preterm babies in the UK during this period received no MBM at all. This seems unlikely.

In the comparison group, babies received MBM and some formula, which could perhaps have been a single feed of formula, or the majority of their feeds as formula, there is no mention of fortification in this group. Infants with a single feed of fortified breast milk and the remainder being formula are placed in this group, as are infants with 99% of their feeds as unfortified breast milk, and a single formula feed.

The use of pasteurized donor milk was between zero and 43% by NICU. In our NICU, use of artificial formula in babies under 29 weeks is about 0%, since the breast milk bank opened in 2014, all babies receive MBM supplemented with donor milk up to 34 weeks, at which time they will receive formula if the baby needs a supplement. Are some NICUs in the UK selective, and choose which babies will get artificial formula?

If we look at the babies of 25 weeks gestation (results from their table 2, with some simple back calculations), there were 75 in the breast milk group (MBM and donor) who never received any fortifier, and their survival without NEC surgery was 29%, there were 167 who got at least a bit of formula, and survival without NEC surgery was 83%.

Taking this at face value, the most effective thing we could do for survival in extremely preterm infants is to give them all some formula!

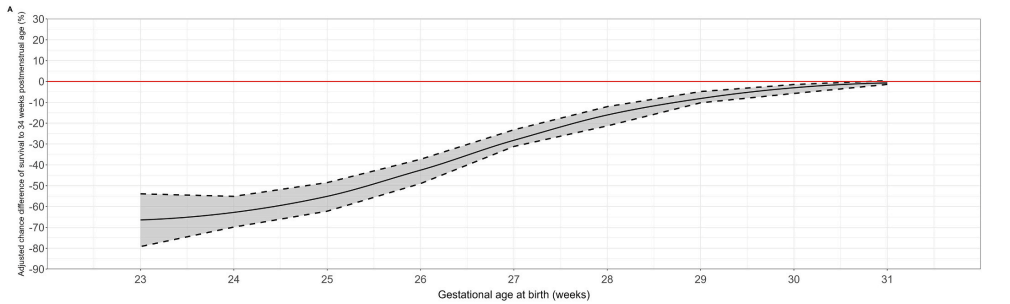

The graph below shows the difference in survival, by gestational age, between the two groups, showing that there is a progressively greater difference in percentage survival as GA decreases, with a suspiciously smooth curve, and an impossibly huge difference at 23 weeks. At 23 weeks there is an extremely low survival with exclusive milk feeding of 15%, but 2/3 survival if they got some formula.

I think the most likely problem with the study is that the data about feeding composition are erroneous. The source of the data is described thus : “The NNRD is a National Information Asset containing a standard data extract (the Neonatal Data Set, an NHS Information Standard; DAPB1595) from the Electronic Patient Records of all admissions to National Health Service (NHS) neonatal units”. The accuracy of the information therefore depends on the accuracy of what is in the electronic patient records, and the precise, accurate transfer of those data from the NHS record to the NNRD, and then the coding from the daily record in the NHS record to the final group assignation in the NNRD.

At some point every single day’s record in the electronic patient record, of what source of feed was given to the baby, which may be 200 or more complex data points, is interpreted and parsed into a single variable in the NNRD. There are so many potential errors in this process that I don’t think it is possible to trust that the group assignment is reliable, without some major data verification.

Who enters the daily feed composition into the electronic record? How is it verified? What method is there for checking the accuracy of those data. If the baby had MBM for 145 days, then a day with both MBM and donor milk, and 10 days with fortified MBM, can the authors say for sure which group they would be in?

There are some other weird things about this publication.

- Admission body weight z-scores were similar between groups, at -0.3 versus -0.1. Discharge weight z-scores were supposedly a mean of 2.5 in the donor milk group and 4.4 in the formula group. These are the biggest preterms at discharge ever reported in the world literature. Really? 4 standard deviations above expected weight at discharge?

- The dietary data were collected until discharge, even though the main outcomes are determined at 34 weeks. An infant who received one feed of formula at 37 weeks (for example) would therefore be included in the formula group, whereas the human milk group apparently never received any formula, or any fortifier, from the day of birth until their discharge home.

- The authors state that there was significantly less BPD in the human milk group. But they calculate BPD as a proportion of the admitted babies, even though a lot of them were dead by 36 weeks! If you recalculate BPD among survivors to 34 weeks (which is in the results, although there were a few more deaths between 34 weeks and discharge (9 vs 55), I don’t know the number of survivors at 36 weeks) BPD was 18.6% in the human milk group and 19.6% in the fortifier group. In other words BPD among survivors was identical.

- Treated retinopathy is also calculated as a proportion of admitted babies, if you calculate as a proportion of babies who survived to discharge, it was 1.1% (rather than 0.8%) in the human milk group, and 2.3% in the formula group, which might still be “statistically significant” I don’t know. There is a typo in the 95% CI of the published unadjusted risk difference in treated RoP, which were -2.1 to “-0.0.8”, so probably very close to being non-significant.

This paper should be retracted. Unless the authors can assure readers that the group assignments were accurate. There should be an external audit of the group assignment for a couple of hundred babies, otherwise we can have no confidence in the results.

They should also redo the analysis based on what feeds were received up to 34 weeks. They could also look at the dose response. Even though they do not know the actual volumes of each source of milk given, the number of days on which a baby received each feed type would be a reasonable proxy. If they could show that the more days that a baby received donor milk was associated with a gradually increasing risk, then this could give a degree of confidence in their analysis.

I do agree with the authors that the data regarding the benefits of human door milk is somewhat soft. But this article does not help. As it is, I have no confidence that these data are reliable, or that these analyses reflect reality.

Some UK insight on practice. Yes there are units that risk stratify a recommendation to use donor milk v formula under 32 weeks, generally using gestation, birthweight and antenatal assessment of end diastolic flow. These are likely to be units that don’t have a milk bank on site. Where I have worked these were smaller local units. Re the daily data, where I have worked it has always been the nurses who have filled in this data, often the nurse in charge after checking in briefly with each nurse (they also need to fill in medications, respiratory support etc so it is definitely a brief check). There is an option to copy the previous day’s data, which is helpful for time saving but I suspect leads to inaccuracy where a change on that day is not noticed and incorporated. Local units do check and verify some NNRD fields but this tends to be the big diagnoses that are reported in national audit eg NEC. Until the last few years, the daily feed data did not contribute to national audit data so was unlikely to have local verification, and it would be very time intensive to verify daily data. However, in an RCT I recently completed, I checked feed data on a specific day in the local data that feeds into NNRD (36 weeks) against maternal report by text message and found 93% agreement. This was exclusive human milk v exclusive formula v mixed, with no consideration of fortifier

Pingback: More thoughts about the “toxicity” of donor milk, a case of Reverse Causation | Neonatal Research

Some studies will yield goofy results despite everything done correctly. That’s exactly why one article shouldn’t change anyone’s practice, right?

That’s generally correct in my view, yes. But this study gives results which are diametrically, and enormously opposed to the previous literature, and everything was NOT done correctly. Babies dying at 3 days of age before the milk was fortified are analyzed in one group. Babies who lived long enough to be get fortified milk were not analyzed at all. Babies who lived long enough to receive formula were analyzed in the comparison group, even if they got it after 34 weeks.

I am still astounded at how bad studies manage to get published and sadly can distort the view of good evidence based medicine. Donor milk, while not the same as a mothers own milk, does not increase risk of mortality in the way this article proposes to readers. It desperately needs to be retracted and redone or analyzed properly.

Pingback: Donor human milk, not toxic after all! | Neonatal Research