I recently gave a presentation to the Pediatrix consortium which was based on our review article about the approach to take after diagnosis of a serious intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) in the very preterm infant. (Chevallier M, et al. Decision-making for extremely preterm infants with severe hemorrhages on head ultrasound: Science, values, and communication skills. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;28(3):101444)

I first reviewed of the prognostic accuracy of severe ICH, making the point that there are 3 different types of haemorrhage which are all called grade 3. That is, those intraventricular haemorrhages that fill more than 50% of a lateral ventricle, those which acutely distend the ventricle, and those where there is blood in the ventricle and early post-haemorrhagic distension of the ventricle. These 3 types of grade 3 ICH may have different pathophysiology, and different prognostic implications, and, usually, it is not clear from a publication describing outcomes what they are including in their definition. The wording of the original system of classification by Lu-Ann Papile et al (based on CT scans) is somewhat ambiguous (“intraventricular hemorrhage with ventricular dilatation”), but the image was shown as an example in that publication, which I reproduce here, is of an ICH with acute haemorrhagic distension of the ventricle. In addition, bilateral and unilateral haemorrhages are put in the same category, and massive distension of the ventricles is lumped with those which have a minor degree of dilatation.

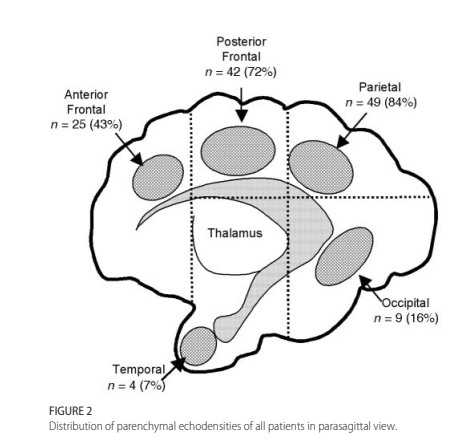

Grade 4 ICH, or intraparenchymal haemorrhage (IPH), is even more variable, with a small echodense spot being put in the same category, in almost all follow up studies, as massive bilateral bleeding with midline shift. There are systems to grade severity among IPH, (many of which are associated with ipsilateral lower grade haemorrhages, and may in that case be referred to as PVHI (peri-ventricular haemorrhagic infarction)). The Bassan system has been used the most. In that system, an ultrasound showing IPH is scored 0 or 1 for each of 3 features, IPH affecting more than one brain region, midline shift, and bilateral bleeding. Thus a grade 4 can have a score of 0, or up to 3.

This figure, form the Bassan study, shows how the brain regions are defined, based on imaginary lines drawn around the thalamus, and the relative proportions according to location.

There is never certainty in prognosis. That is a simplistic truism in all of medicine (or all of life!) but it is particularly true after ICH in preterm babies. Given the limited data we have, grade 3 hemorrhages, which are not accompanied by an IPH and are not followed by post haemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD), probably have little impact on development or motor function.

Grade 3 haemorrhages with subsequent progressive dilatation have impacts on motor function, and probably on language and cognitive development, but, in the absence of IPH these effects are relatively small, especially if early derivation is performed.

IPH outcomes vary between no impact and major global delay with tetraplegic CP. For an individual baby, the correlation between location and extent of the IPH on ultrasound and motor or developmental outcome is limited, and very variable in the reports. For example it has been reported that anterior IPHs are more likely to be associated with CP, or posterior IPHs, or that there is no effect of location. There seems to be an association between extent of the lesion and the presence of more severe developmental problems in the long term, and the Bassan classification does show some gradation in outcomes, IPH which score 0 or 1 having no major impact on long term outcomes, and those of 2 or 3 being associated with an increased risk of… you got it , “NDI”! In all the studies however, even the worst IPH may be followed by only mild long term abnormalities.

Several studies show that outcomes are affected more by other complications of neonatal care than they are by ICH. For example, this figure (Merhar SL, et al. Grade and laterality of intraventricular haemorrhage to predict 18-22 month neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely low birthweight infants. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(4):414-8) shows that a bilateral IPH in a baby who does not receive dexamethasone, and does not have an episode of sepsis, has a better prognosis (in terms of proportion with “NDI”) than a baby with bilateral sub-ependymal haemorrhage who has both of those factors.

What to do with these uncertainties? It would be simple to never make a decision, and only concentrate on the prognostic uncertainty. “We can never know for sure” is an important thing to say, but it doesn’t mean that should ignore a major increase in risk for an individual. There is no finding on head ultrasound that universally predicts a profoundly limited outcome. For example, in a study from Western Australia, evaluating another severity scoring system, the one child with the maximum possible score, which is assigned to bilateral haemorrhage affecting multiple regions on each side and with midline shift, had only minor impairment.

One way of dealing with this is to ensure that parents know that they can dispose of all of our best information, if they wish. Katherine Callahan just published this piece in JAMA (Callahan KP. Discarding Information. JAMA. 2023), describing interactions in which the carefully prepared decision aids, and nuanced documents, trying to explain risks, are sometimes binned by parents, she suggests that that is just fine, that we should say to parents: “You deserve this information, but you also deserve to know it is not perfect. You can choose to discard it”.

As I suggested in my Pediatrix talk, the most important decisions in our lives are not usually rational. Getting married, having kids, or adopting, deciding on a career; these are all things that we decide on without necessarily listing pros and cons, adding the weights of each one, and then making an evidence-based decision. For these major decisions, we usually go with our heart, and what we hope will create the most happiness and fulfillment for the future. Sometimes, as health care workers we are upset that parents make what we consider to be irrational decisions; but a perfectly rational, unemotional decision can only be made by individuals who would not be competent to be parents. (For a really interesting discussion about this, you could read Charland LC. Is Mr. Spock mentally competent? Competence to consent and emotion. Philos Psychiatr Psychol. 1998;5(1):67-81).

A new systematic review of the outcomes of neonatal stroke (Giraud A, et al. Long-term developmental condition following neonatal arterial ischemic stroke: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr. 2023). points out the uncertainties of prognostication in those babies also. They include this figure, as a suggested tool for counseling parents about prognosis.

There is a lot to like about this figure, especially the last section introducing things parents can do to promote development, but I am unsure about the reliance on percentages. Many people, physicians included, don’t understand what percentages like those mean for an individual child. There are studies to show that rates of outcomes are better understood than proportions. It is probably generally better to talk about how many children, out of a hundred children with a stroke, will have no learning difficulties in primary school, and how many will have difficulties.

The review article points out the high frequency of neurological or developmental concerns, but in fact most of the babies in the cohorts were functioning well. The first 4 lines on that figure about child development are all about the negative outcomes, even though they are a minority. Why not state them as positives?

“Of 100 children who had a brain problem like your child, 90 of them will go to normal school, but 10 will need special help with schooling. 70 out of every 100 children will do well at school, but 30 will have learning difficulties” might be easier to understand and focuses on the positive outcomes, experienced by the majority of children.

The plasticity of the neonatal brain makes our job, as prognosticators, more difficult and more uncertain than at any other age. Much of what is important in long term outcomes is invisible on brain imaging. From details of brain interconnections, to the rewiring of damaged regions, to family connections, parental interactions, how many books the family owns, attitudes to impairment, and future educational improvements; indeed all of the environmental influences on outcomes, that we can know little about in the NICU.

It is vital that we learn more about those other influences on outcomes and how to use them, but prognostication will always be uncertain, especially in the neonatal period, and even more so in the first few days after birth. We must be honest and transparent, and recognize and express the uncertainties with parents, while never minimizing their hope.

There is always room for hope, which may need to be adjusted but never destroyed. Hope in parents is associated with improved quality of life (Nordheim T, et al. Hope in Parents of Very-Low Birth Weight Infants and its Association with Parenting Stress and Quality of Life. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:e53-e8), and parental peer support groups seem to enhance hope among participants (Dahan S, et al. Community, hope and resilience: parental perspectives on peer-support in Neonatology. J Pediatr. 2021;243:85-90 e2). Shared decision-making is enhanced when caregivers and parents share hope (Koch A, et al. Crossroads of parental decision making: Intersections of hope, communication, relationships, and emotions. Journal of child health care. 2023;27(2):300-15).

In “Candide”, Voltaire’s character Pangloss is a tutor of philosophy who believed that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds”, despite the evidence all around him, of the Lisbon earthquake which killed tens of thousands, and the Seven Years War which was raging. We must, in contrast remain reasonable and aware of the difficulties of some of those with major brain injury. We can express and inform parents about the range of possible, and likely, outcomes after a brain injury, while also recognizing the uncertainty of the future.