Although babies under 25 weeks account for a tiny proportion of births, and a small proportion of NICU admissions, the importance of the question asked in the title can be seen by the ongoing number of publications, below are just a few of recent relevant publications of interest.

Wood K, et al. Individualised decision making: interpretation of risk for extremely preterm infants-a survey of UK neonatal professionals. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021.

Di Stefano LM, et al. Viability and thresholds for treatment of extremely preterm infants: survey of UK neonatal professionals. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106(6):596-602.

These first 2 are results from a on-line survey study in the UK. The 336 respondents were 50% neonatologists, but, as an on-line study it is hard to know how representative the responses are. Nevertheless it really suggests a shift in attitudes, with respondents more likely than in previous years to accept active intervention at 22 weeks, and to take into account other risk factors than just gestational age. A major concern I have with these types of decisions is that they are often based on risk of mortality, and also on risk of “major impairment”. Although what this means is discussed in the “framework” document, and is generally intended to mean a severe intellectual impairment (IQ <55), disabling CP, blindness or profound hearing impairment, I don’t think that the implications of that label are necessarily always explicit. Especially in an online survey, which didn’t, as far as I can see from the supplement, re-iterate the criteria for a definition of major impairment.

Do we really think that an increased risk of blindness is a good reason for denying intensive care to babies? Or disabling motor dysfunction with a normal intellect? I think in reality that it is the risk of severe intellectual impairment which drives all of our concerns about “severe impairment”, and that we should acknowledge that. To take this further, if a baby was born needing resuscitation at term, with known congenital blindness, would it be ethically acceptable to deny that baby intervention because of known (rather than a predicted statistically increased chance of) blindness? We could ask the same thing for congenital deafness, and for GMFCS of 3 or 4 (level 3 meaning able to walk with a hand-held mobility device, and level 4 meaning self-mobility is limited, may need a wheelchair, but usually with head and trunk control), if we had a definite diagnosis of those impairments prior to birth would it be justifiable to withhold intensive care? I think we should focus on the outcomes we really worry about the most, level V GMFCS, and very severe intellectual impairment. They are outcomes which are relatively uncommon, even at the most extreme gestational ages.

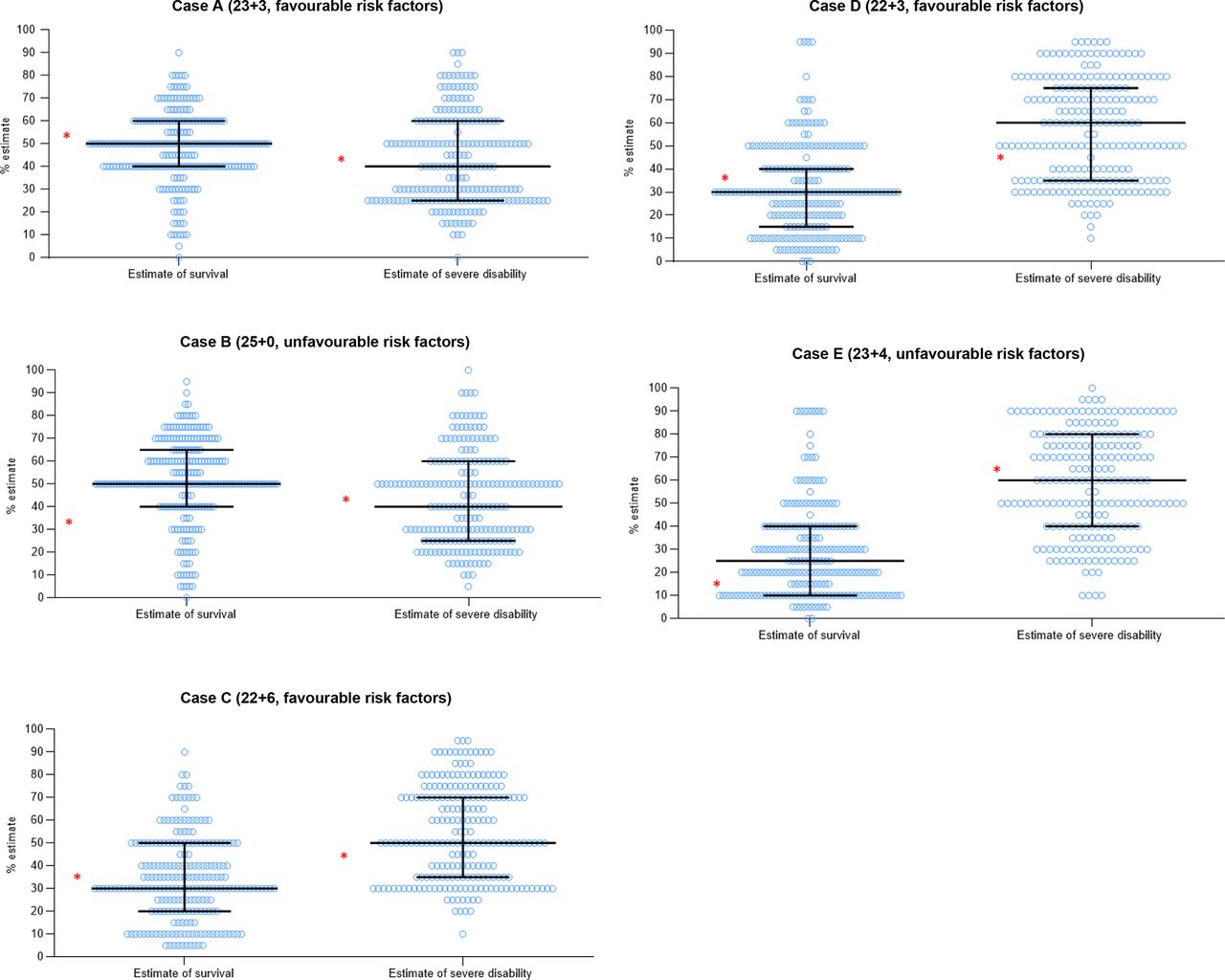

In addition, in this study, the respondents were asked to estimate the probability of death and severe impairment, and the responses were extremely variable. This figure shows the range of opinions about potential survival and proportion of “severe disability”, each dot represents one response, the horizontal lines are medians and IQRs, and the asterisks are estimates from the on-line NICHD risk calculator. However, the NICHD calculator now gives a range of outcomes, rather than a point estimate, and the definitions of profound impairment, etc. are not the same as the BAPM definitions. The data do show major variability in estimates of survival and long term outcomes.

This survey study asked physicians involved in perinatal care what makes an acceptable quality of life, and what proportion of infants born at various extreme gestational ages would be likely to have an acceptable QoL, and then what their own resuscitation preferences were. One notable finding is that very few respondents had any encounters with former very preterm children, and those with the fewest encounters, in particular obstetricians, had the most negative views of quality of life outcomes.

There was a close correlation between having a negative opinion of the QoL of extremely preterm infants, and not wishing to actively intervene. This has been shown before; the over-estimation of serious adverse outcomes drives an unwillingness to actively intervene.

The belief that there is a dramatic reduction in the proportion of survivors with an “acceptable quality of life” as GA gets lower is a common prejudice that is not based on any data. As you can see from this graphic from a systematic review of long term outcome studies (Ding S, et al. A meta-analysis of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 4-10 years in children born at 22-25 weeks gestation. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108(7):1237-44), there is very little difference in “severe disability” between 22, 23, and 24 weeks, with a trend to more moderate disability.

Of course, an unacceptable quality of life is by no means equivalent to severe disability, the large majority of disabled children have a good quality of life, there is nothing in the literature to support the prejudice against extremely immature babies, that supposes that they have a high probability of an unacceptable quality of life.

One other disturbing result of the LoRe study was the belief that having an extremely preterm baby would have a negative impact on the family as a whole, a belief held by 73% of the respondents. There is absolutely no data to support this, the large majority of families report both positive and negative impacts of very preterm delivery. Of course there are challenges, sometimes major challenges, but living with a former extremely preterm infant does not have an overall negative impact on families.

In this study parents were counselled about threatened extreme preterm delivery at between 23 weeks 0 days and 24 weeks 6 days, they and their physicians then completed questionnaires about shared decision making, and they were later followed up to see if they experienced decisional regret. This study took place in the Netherlands, where active care is generally not offered at 23 weeks gestation, and, in fact, the mothers included in this study all delivered at 24 weeks (n=3) or later. To be brutal, shared decision-making does not occur in the Netherlands for babies born at <24 weeks gestation. Parents are given no share in that decision. Four of the 22 counselling sessions resulted in a decision for perinatal palliative care, there were low scores for decisional conflict, and, from the few surveys returned 1 month later, little decisional regret. I can’t tell from the publication if any babies actually died after receiving perinatal palliative care or not, which is an important limitation. Decisional regret is relatively uncommon after many different decisions in life, we all tend to believe in retrospect that we probably made the right decision. Decisions which lead to a child dying may be different, especially if you later discover that your baby had a greater chance of survival, and of survival with a good QoL, than you were informed. Another study by this group showed no significant difference in decisional regret according to the decision taken, but there were only 4 who had a decision for palliative care, and 2 of those 4 had high scores for decisional regret.

De Proost L, et al. On the limits of viability: toward an individualized prognosis-based approach. J Perinatol. 2020;40(12):1736-8. This article is a commentary, the authors of which include the first author of the previous article, pleading for a revision of the Dutch guidelines to take into account other factors than gestational age, and against a rigid guideline based on GA alone. Indeed, I think it is about time; survival of babies in Holland at 24 weeks is substantially lower than many other jurisdictions, and survival of babies at 23 weeks gestation is 0. This is despite a high quality health care system, dedicated staff, good regionalisation, excellent training, all the things that are needed to have excellent results. I think Dutch families deserve better.

Overall, I think these articles give me some hope that things are changing in the right direction, caregivers are more willing to intervene for more immature babies, and some prominent physicians are working to promote individualized decision making, rather than blanket denials of active care. There is a still a crying need for education, otherwise couples with threatened extremely preterm delivery are being given information which is biased and inaccurate.

In particular we need further exploration of which outcomes parents in general find unacceptable (other than death), and also how to elicit individual parental preferences within the antenatal decision making framework. One recent publication asked mothers and their partners with threatened delivery between 22 weeks and 24 weeks 6 days about their attitudes to outcomes, including various impairments, (Tucker Edmonds B, et al. Values clarification: Eliciting the values that inform and influence parents’ treatment decisions for periviable birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020;34(5):556-64). This is one table from this fascinating study from Indianapolis

Among the participants of this study, “the majority described a good QoL in terms of emotional well-being (eg “loved”, “happy”, “supported”), whereas a poor QoL was described in terms of functionality (eg “dependent” and “confined”)”. They were a mix of different ethnic, religious, educational and financial backgrounds, but the sample is too small to analyze whether those factors were important in their attitudes.

It has been shown several times that healthcare workers attitudes differ from the rest of the population, I think probably rather more than 54% of caregivers would agree that “some disabilities are worse than death”, certainly that is the implication from the study by LoRe et al, but this study from Indianapolis had a substantial number of respondents who disagreed with that statement.

Update: Jan 10 2022; I slightly changed the title of this post, from “how do we make decisions for the most immature babies, and their families” to “how do we make decisions for the most immature babies, with their families” as I think that better reflects the subject matter (about shared decision-making) and my feelings of how we should partner with families to make the best decisions for our patients.

Pingback: What do we tell families at 22 weeks? | Neonatal Research