In order to respond to the question posed in the title we need first to agree on what “futile” means. It could mean “it never works” or, “it can work but the ultimate result is so bad that it isn’t worth doing”, or “it works so rarely that the effort and resources required are enormous, and it therefore isn’t worth doing”.

In neonatology, and clinical care in general, the term has been used to mean each of those 3 things (you could probably come up with other definitions), the response to the question depends on which you think is most appropriate.

Clearly “it never works” is not true, sometimes babies born between 22 weeks and 22weeks and 6 days do survive to go home.

In fact the proportion of survivors can be impressively good. (Backes CH, et al. Outcomes following a comprehensive versus a selective approach for infants born at 22 weeks of gestation. Journal of Perinatology. 2018). In this article the authors compared outcomes between a center in Sweden (Uppsala) and one in the USA (Nationwide Children’s, Columbus Ohio). There may be multiple differences between the populations and the medical approach, but the authors focused on what is probably the most important, that is the proportion of mothers and babies with threatened profoundly preterm deliveries who received comprehensive active care.

You could probably characterise the approaches as “Opt-out”, in Uppsala, the default approach is to counsel the parents with the attitude that active intervention is usual and is encouraged by all the team, compared to “Opt-in” where the team attempts to obtain a consensus regarding active intervention, and the parental choice is the priority.

In the article the authors refer to these approaches as a comprehensive approach, and a selective approach.

In Uppsala over a 10 year period (2005-2016) there were 33 mothers who delivered 41 live born infants between 22 weeks and 22 weeks + 6 days best-guess gestational age. All chose active intervention, all received antenatal steroids (and 85% were able to have a 2nd dose), all had surfactant in the delivery room by a team being led by a neonatologist, and 38 survived to NICU admission, none had a cesarean delivery.

In Columbus over the same period there were 64 mothers who delivered 72 babies. Twenty percent (13) received steroids, and 9% (6) had 2 doses. There were 16 babies who had active interventions, 56% (9) had surfactant in the delivery room, a neonatologist was present 75% of the time (11) and 31% (5) were delivered by cesarean (another 2 mothers who did not have active neonatal care also had a cesarean).

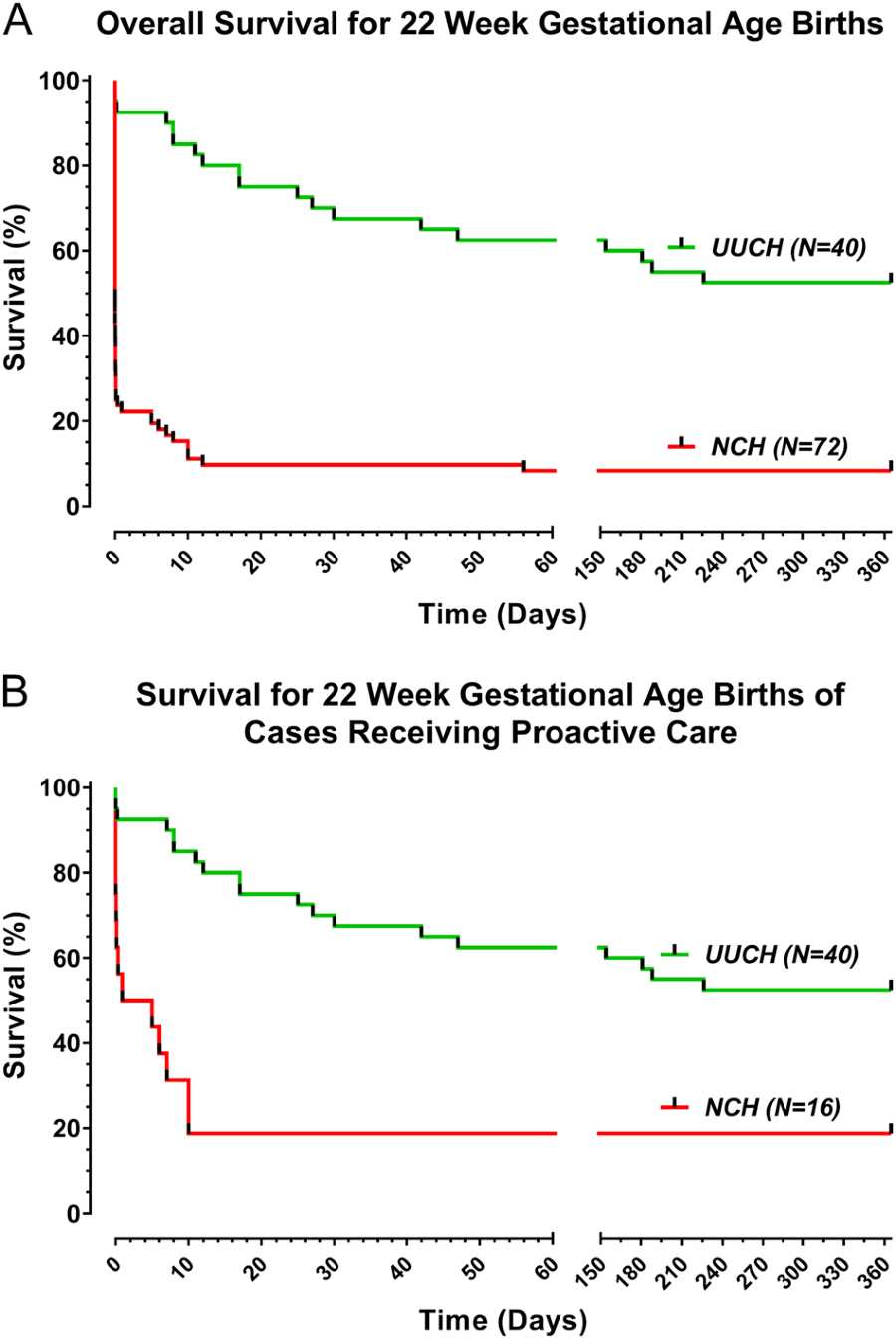

You can see from these survival curves the dramatic difference in mortality between the 2 centers when you include all the live born infants (panel A) or only the babies that received active interventions (panel B).

When the analysis was corrected for multiple risk factors, the relative impact of being born in a center with uniform comprehensive care was actually increased. In other words the babies in Uppsala receiving active care were not heavier, or with lower risk factors, in fact the opposite is true, birth weight averaged 489 vs 527 g and there were more twins. The Odds Ratio of survival after correction was 14.47 (95% CI 3.09, 68.7) in Uppsala compared to Columbus.

This post is by no means a criticism of Columbus, they seem to have an approach similar to many centers in North America, indeed, they are more open to active intervention at 22 weeks than some centers, which refuse to intervene. Their survival rate among actively treated babies is well within the range of those reported for good quality centers. I applaud them for collaborating in this study. Survival to hospital discharge was 53% in Uppsala, and 8% in Columbus, but 19% among those who received active care.

So it is clear that active intervention at 22 weeks cannot be called futile, if by which we mean it never works. But what about the “ultimate result”? This article also includes some follow-up data from all of the survivors at Columbus, and all but one of the survivors in Uppsala. In Columbus all of the survivors had moderate to severe impairment. In Uppsala 20 of the 21 survivors were evaluated, 11 had no impairment, 2 were mildly impaired, and 5 had moderate to severe impairment.

Is the team in Uppsala unique? Are they the only ones to achieve such results, such that we cannot think of extending their success elsewhere? The group in Cologne (Mehler K, et al. Survival Among Infants Born at 22 or 23 Weeks’ Gestation Following Active Prenatal and Postnatal Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):671-7) have published their results of an approach that lies somewhere between these 2 centers, that is a selective approach, but one that ends up with a higher proportion of active intervention. They report 45 live births at 22 weeks, 28 of whom received active interventions (62%), they had 61% survival among those 28 babies at 22 weeks, or 38% if expressed as a percentage of live births.

Are such results possible in North America?

I was just invited as a guest speaker in Iowa, at their first symposium on care of the periviable infant. This was a very high quality small symposium, presentations regarding approaches to the profoundly preterm infant, use of steroids, clinical practices, nursing practices etc. Much of the discussion after the talks was focussed around practices at the University of Iowa, because they have had a policy of encouraging active intervention for many years at 23 and then at 22 weeks. That policy has led to an amazing depth of experience, and a great wealth of knowledge.

Although they are currently trying to publish their results, and therefore there are not a lot of references that I can give, their results of survival among all liveborn babies at 22 weeks gestation, between 2006 and 2016 are 59%. In the most recent period that appears to be more like 65%. They are currently in the process of publishing some results, so I won’t give away any more details, but I am confident that the survival figures are accurate.

Centers who usually, or almost always, give active care to the most immature infants at 22 weeks have survival figures that are better than I thought was possible a few years ago. To achieve such a result you must have a coordinated approach with obstetrics, and administration of steroids whenever active intervention at that gestation is likely to occur. A positive attitude is very important, a belief that it is possible to have good survival, both in terms of percentages and in terms of quality of life of survivors. In Columbus there were a number of families in which there was “inconsistent care”, i.e. the approach of the obstetrical and neonatal teams differed, very often that is active intervention at birth but no steroids being administered, despite having the time to do so, but we don’t know that specifically from this study. The other point is that active intervention does not imply cesarean delivery, mode of delivery is a separate decision, and making that decision requires other considerations, such as the intended reproductive future of the mother. Very good survival without using cesarean delivery is possible.

Is there a downside? If you frequently institute active intervention in babies at such high risk, there will be many complications. As you can see from the data from Uppsala, there were several late deaths, one after 226 days of NICU care, whereas in Columbus death usually occurred early, the latest being at 10 days. The frequency of complications in all of these cohorts, (NEC, sepsis, BPD, RoP brain injury on ultrasound) is high. But survival at quite reasonable frequency is possible, in multiple centers, and many survivors do not have major impairment.

I don’t think that futility can any longer be used as an argument for not actively intervening at 22 weeks.

Pingback: Not futile any more; survival and long term outcomes at 22 weeks. | Neonatal Research