An excellent acronym for this trial. Hopefully it will lead to a trend in acronyms based on European culinary specialities. Very preterm infants, n=151, of 23 to 32 weeks GA were randomized to receive delivery room CPAP with a face mask, or with a nasal mask in a single centre study from Monash in Melbourne. Delayed clamping was attempted, without respiratory support, or immediate clamping if the baby needed intervention. If the baby needed positive pressure ventilation, that was delivered by face mask, the same in the two groups. When the babies could be placed on CPAP, they randomly had either a face mask placed, or a nasal mask.

If the nasal CPAP was unsuccessful and the baby needed PPV, they were switched to a face mask. The authors supply some videos of the procedures, including this one of a baby started on nCPAP, then changed to face mask PPV.

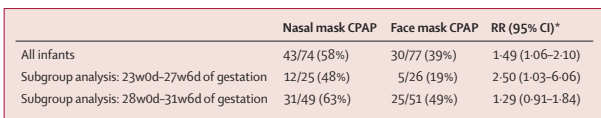

The primary outcome of the trial was CPAP success defined as the “proportion of infants managed with CPAP only (ie, without positive pressure ventilation, intubation, chest compressions or adrenaline) between birth and transfer to the NICU. If a newborn received no respiratory support, that was considered success of the treatment group.” The proportion of CPAP successes are shown in the following table.

All the usual clinical outcomes were similar between groups. Admission FiO2 was lower in the nasal group.

It looks like the advantage of nasal, compared to face mask, CPAP was because more of the face mask group required PPV, 47/77, compared to 31/74 nasal mask subjects. This is consistent with previous findings that face mask application can cause apnoea. Stimulation of the trigeminal nerve area can provoke respiratory pauses, and bradycardia, and it seems that the nasal mask, creating pressure over a much smaller area around the base of the nose, does not have this effect. The authors note that the starting pressure was intended to be 5 to 8 cmH2O in the 2 groups, but that the clinicians started the nasal CPAP at an average of 1 cmH2O higher in the nasal group. The nasal group also had heated humidified gases, compared to the cold dry gases in the face-mask group. These 2 differences are potential confounding reasons for the difference between the 2 groups. But, because fewer nasal group babies had PPV, the peak inspiratory pressure applied was lower in that group than the face mask group.

Despite these limitations, it seems that there may well be significant advantages in applying a nasal mask, compared to a face mask, for CPAP in the delivery room in the extremely preterm infant. Although the authors did not show any improvement in clinical outcomes (the study was not powered for such outcomes), any intervention which decreases the need for PPV during transition is probably a good thing for lung protection.

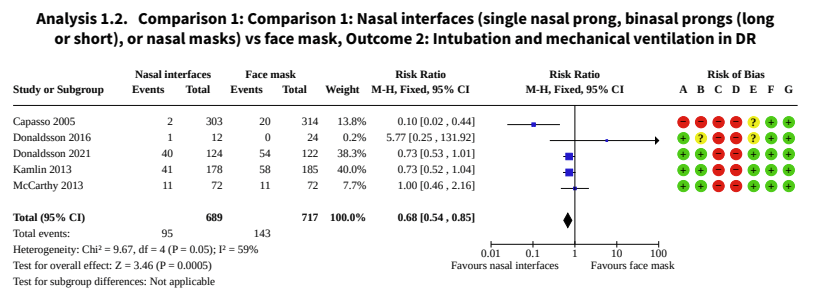

To put this in context of previous research, the Cochrane review, Ni Chathasaigh CM, et al. Nasal interfaces for neonatal resuscitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;10(10):CD009102, which did not include data from this trial, showed a reduction in the need for intubation in the DR with nasal interfaces compared to face mask. The 5 trials included in the Cochrane review were fairly heterogeneous: one included term infants; the nasal interface was a short nasal prong in 2 trials, short binasal prongs in 3 trials; and with a different device generating the pressure in the 2 groups in 2 of the trials. The Cochrane review showed a reduction in DR intubation, of note, this new trial had very few DR intubations, 6 in the nasal group and 7 in the face mask group; adding this to the Cochrane MA will have little impact, the weight will be small, and the tiny difference is in the same direction as the current MA results.

The review also showed less babies needing chest compressions, but that outcome was entirely dependent on the one trial that included full-term infants.

In the Donaldsson 2021 study the large majority of infants (<28 weeks) in both groups >82% received PPV. In Kamlin’s study, about the same proportion received non-intubated PPV (just over 50%) but fewer were intubated, McCarthy et al don’t seem to report how many infants needed PPV.

My interpretation of this is that it would be preferable in the very preterm infant to avoid face masks for initial CPAP support in the DR. It appears that the advantages of nasal prong systems and a nasal mask are similar, overall there is a reduction in the need for intubation in the DR, and perhaps for PPV.

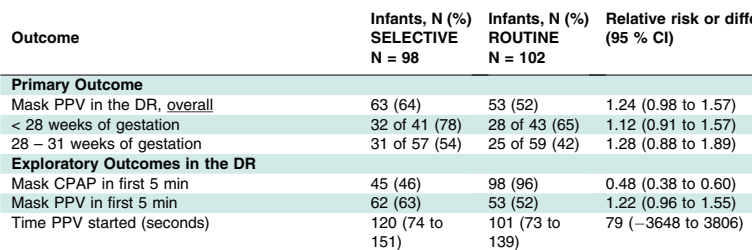

This RCT from Colm O’Donnell’s group at the national maternity centre in Dublin enrolled 200 babies <32 weeks. The idea was to determine if there was an advantage to routine immediate CPAP application, using a round Fisher-Paykell face mask, cold dry gases, and a t-piece resuscitator. The comparison, selective, group had face mask CPAP (using the same system) applied if they developed signs of respiratory distress after 5 minutes of age. Infants in both groups had standard resuscitation, with PPV being started if they were apnoeic, or if they had a heart rate <100. The primary outcome was the requirement for PPV. Although the difference in the primary outcome was small and not statistically significant, more babies in the selective group required PPV in the DR, in both GA strata, and nearly half of the selective group received early CPAP (before 5 minutes).

More extensive resuscitation (intubation, chest compressions) was very similar between groups, as were all the clinical outcomes after NICU admission. Although the study did not show any differences that were “statistically significant”, there were no benefits to delaying CPAP.

My interpretation of all this is that the very immature infant would probably most benefit from early CPAP applied with a nasal interface. I like the idea of using a nasal mask to avoid the potential trauma of inserting a nasal prong; prong insertion can usually be done gently, but sometimes, especially in the smallest babies it is a tight fit and probably hurts. A really useful trial would be to investigate routine early CPAP with a nasal mask, which can also be used for PPV, compared to using a face mask according to current NRP standards.

Dear Keith. Thank you for the review. I am always concerned about the trigeminal cardiac reflex in these babies and have seen babies become bradycardic during PPV using a facemask, only to improve after removing the mask when you decide to intubate them! We typically transition to the Hudson prongs CPAP as soon as feasible in the delivery room. I wish there were simple nasal prongs available to deliver PPV. I know RAM cannula has been used for that purpose, but the evidence is sketchy and comes from retrospective studies (eg Petrillo et al., DOI: 10.1055/s-0039-1692134). There is one noninferiority RCT comparing RAM cannula with short binasal prongs for NIPPV but not in the delivery room (Hochwald et al.; DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3579). There is some evidence to suggest needing higher pressures to overcome the resistance of the long tube. I am interested in hearing your opinion on using RAM for PPV in the delivery room. Thanks

Fayez Bany-Mohammed, Neonatologist, UC Irvine