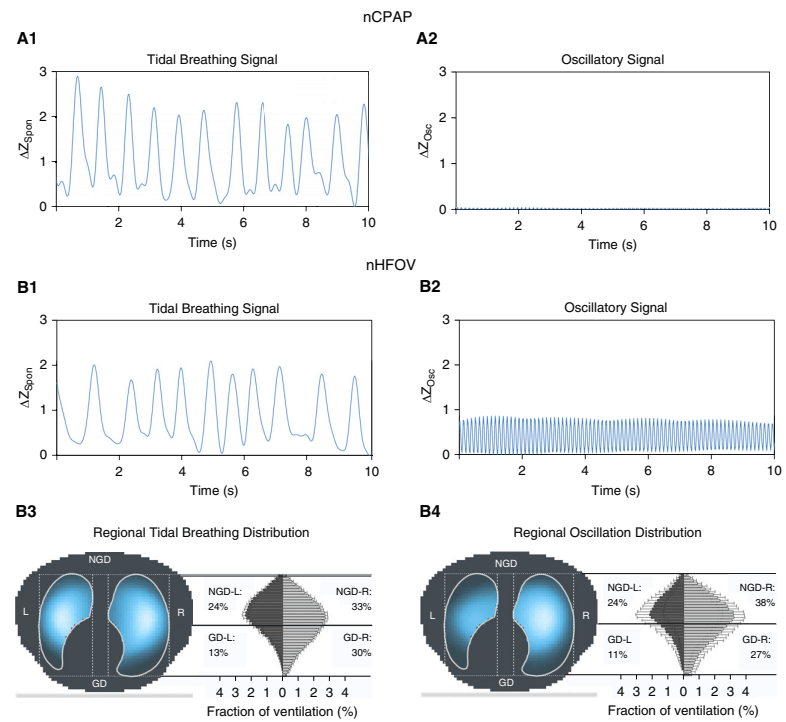

Non-invasive HFOV can be delivered by a variety of different equipment and interfaces. The high flows and upper airway turbulence probably have an impact on gas exchange; It appears that the effective dead space of the oro-nasopharynx is washed out (De Luca D, Dell’Orto V. Non-invasive high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in neonates: review of physiology, biology and clinical data. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016;101(6):F565–F70), but how much transmission of the oscillatory pressures to the lung occurs is uncertain. Transmission does occur under some circumstances, however, as several groups have shown. In this cross-over study, for example, (Gaertner VD, et al. Transmission of Oscillatory Volumes into the Preterm Lung during Noninvasive High-Frequency Ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(8):998–1005) nHFOV was applied starting with a pressure amplitude of 20 cmH2O, then adjusted to give either a PCO2 of 40-60, or, if, the baby was already normocapnic, adjusted to the lowest pressure that gave visible chest wall oscillations, the article doesn’t state what were the eventual pressure amplitudes received. Nevertheless, using transthoracic impedance tomography, they were able to detect chest wall movements which were about 1/5 the amplitude of the babies tidal volume movements. They also showed that when the oscillations were switched on, there was a decrease in the amplitude of the infant’s own tidal respiratory movements, which I presume was a reflex reduction, secondary to an increase in CO2 clearance by the HFO, which would decrease endogenous respiratory drive.

The figure shows the amplitudes of impedance changes over a period of CPAP compared to nHFOV, i the upper panels, and the lower coloured pictures show that the oscillations were preferentially transmitted to the right lung, especially the central and “upper” regions (the babies were in ventral positioning).

It appears likely, then, that there are some pressure oscillations in the distal airways during nHFOV, which might lead to some gas exchange. It is possible, therefore that respiratory support of nHFOV may have some advantage over CPAP. Any possible advantage over nIPPV (with NAVA or fixed pressures and/or non-synchronised) is not so clear, and requires some clinical trials to confirm.

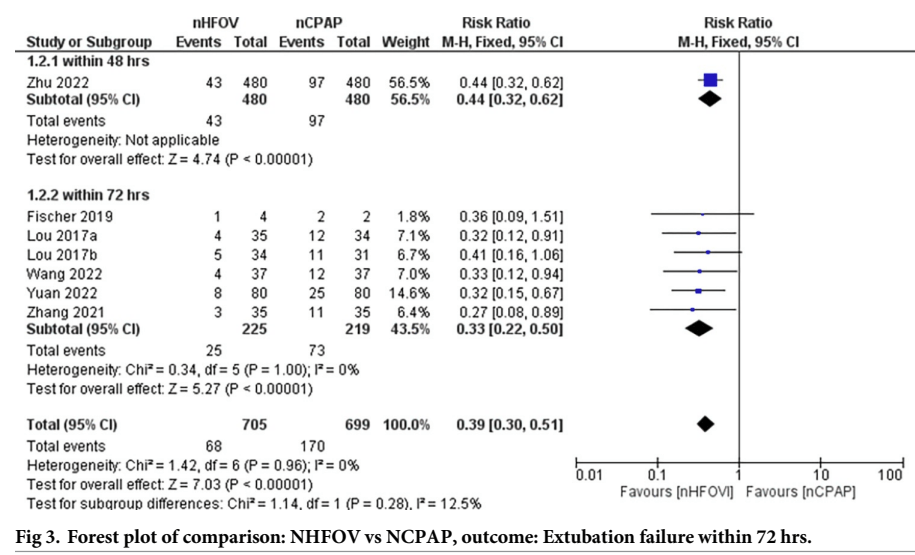

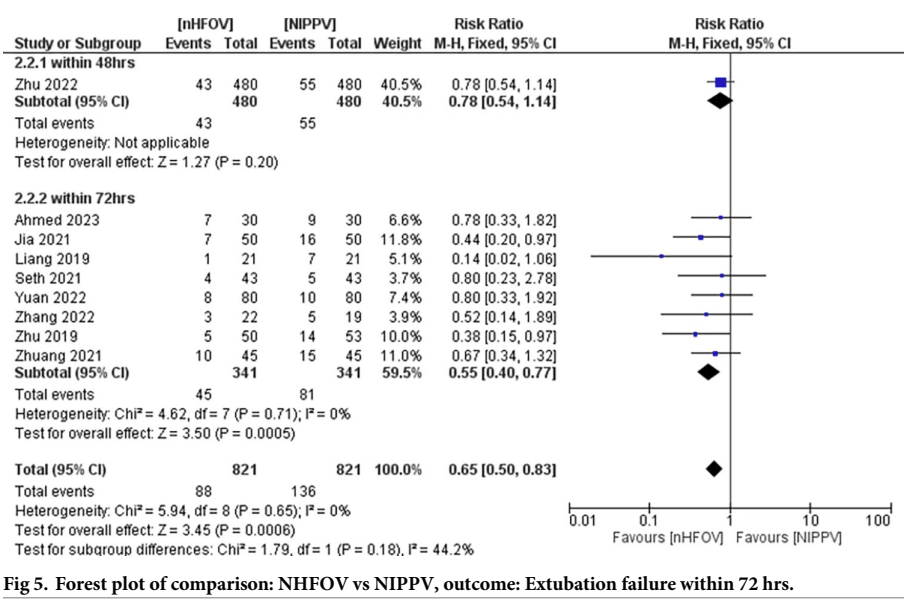

There have been a few recent trials of nHFOV, both as a mode of routine support post-extubation, and for primary respiratory support after birth in preterm infants. There are also now several systematic reviews and meta-analyses, there seem to be some SR/MA factories churning these things out, some of which appear to have been written with AI, and sometimes include non-existent references. One needs to be really careful these days, both as a reader and as a peer-reviewer. I now check much more carefully than in the past when I am peer-reviewing an article (both primary research and review articles) to be sure that the key references actually exist. Unfortunately I don’t read Chinese, and many references only seem to appear in Chinese databases. In this SR of post-extubation nHFOV, for example, Prasad R, et al. Noninvasive high-frequency oscillation ventilation as post- extubation respiratory support in neonates: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0307903 there are numerous included RCTs for which I cannot find the original article, some appear to only show up when searching the Chinese medical publication database, so it is impossible for me to check the definitions of treatment failure, for example, or the characteristics of included babies.

That review shows a reduction in extubation failure when nHOV was compared to nCPAP

and a smaller advantage of nHOV compared to nIPPV

That review showed no difference in any other clinically important outcomes, such as lung injury as measured by BPD at 36 weeks, IVH, or the other usual neonatal complications.

It also is not clear if all the babies benefited from an optimal approach to extubation, with caffeine pre-treatment, evaluation of spontaneous breathing, and higher CPAP levels in those still requiring oxygen, all of which can reduce extubation failure rates, and might eliminate a possible advantage of nHFOV, or not. They are also all tiny or modestly sized trials, only one of which was individually significant, which inflates the probability of a chance finding.

In addition, as mentioned, there are some problems with availability of these publications. The reference list of this SR/MA has no entry for Zhu 2019, it is supposed to be reference 37, but reference 37 is a different publication, a non-controlled report of nHFOV use, and I can’t find any link to a trial of nHFOV authored by Zhu in 2019, including from searching the Chinese database, CNKI. Also Liang 2019, and several other references, does not have a URL link; I searched the CNKI database and found a link to the Liang article, which had an abstract in English (the things I do for my readers!), but the full publication is behind a paywall, so I have no idea how extubation failure was defined in that study.

The systematic review seems to show that nHFOV post-extubation leads to a decrease in extubation failure from an overall rate in these studies of 1 in 4 with CPAP, (which seems very high) to about 1 in 9. In the studies comparing with nIPPV, the overall rate decreases from 1 in 6 with nIPPV to about 1 in 9 with nHFOV. But, if you eliminate the trials that I cannot find, and the tiny trial with an extremely high failure rate in controls, there is no clear advantage to post-extubation nHFOV compared with nIPPV in extubation failure.

Failing extubation and being re-intubated is, in itself, an important outcome to parents (and I would guess to the babies!). If there were no other advantage in terms of lung injury, VAP, or length of stay, then that in itself would be worth the hassle. For now, I am not convinced of the advantage of nHFOV compared to nIPPV for routine support post-extubation in the very preterm infant (who has the highest chance of being re-intubated). Other interventions, including NIV-NAVA (Tome MR, et al. NIV-NAVA versus non-invasive respiratory support in preterm neonates: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Perinatol. 2024;44(9):1276–84) also are unconvincing as evidence for routine use.

The current evidence shows that prior to extubation babies we should ensure therapeutic caffeine treatment, perform a Spontaneous Breathing Test, and if the baby passes the test, very preterm infants should receive either nIPPV, nHFOV, or NIV-NAVA, with a PEEP of 6 if in 21% oxygen, and 8 or 9 if they have residual oxygen needs.

Decreasing extubation failure, and the need for reintubation, with its resultant trauma to the airways, and trauma to the parents hopes, is an important goal for research, even if longer term pulmonary complications are not affected.

I can see you’ve written blogs on the SBT and the CPAP levels post extubation in 2012 and 2013, has there been any more recent evidence to support or refute those rules of thumb for extubation success?

I don’t think there is much more recent data to help us in successfully extubating preterm infants. I can imagine in the future, that higher doses of caffeine might prove helpful. I think it is important to ensure good nutrition, as malnourished babies are probably more likely to fail. Apart from that, trying to get the timing right is key, the SBT helps, I am sure, but it is not foolproof, and maybe other ways of predicting success might be preferable in the future.