One of the pivotal RCTs in neonatology was the CAP study (Schmidt B, et al. Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(19):1893–902). We performed that study because there was no data on the long term impacts of caffeine, and there was a worry that blocking adenosine receptors in babies having multiple hypoxic episodes might be a bad idea. Adenosine is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that is produced during hypoxia, and decreases the brain metabolic rate to protect against hypoxic damage. So giving caffeine to babies having a lot of apnoeas could potentially have been a bad idea.

As it turned out, caffeine, given for a few weeks in the neonatal period, to babies <1250g birth weight who, in the first 10 days of life were thought to have an indication for caffeine by the attending physician, had a lasting positive impact, with some fine motor benefits even out to 11 years of age (Murner-Lavanchy IM, et al. Neurobehavioral Outcomes 11 Years After Neonatal Caffeine Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5)). Why is caffeine so beneficial? It could be because of a reduction in apnoea, and in the consequent intermittent hypoxia, it also appears to have effects on cerebral oxidative injury and on apoptosis. There is one article, for example, from a study in mice, which showed that caffeine reduced hypoxia-induced white matter injury (Back SA, et al. Protective effects of caffeine on chronic hypoxia-induced perinatal white matter injury. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(6):696–705).

The dose of caffeine that we gave was based on the data available at the time, it appeared to have a wide margin of safety, so the standard dose that we settled on, a 20 mg/kg load of caffeine citrate, followed by 5 mg/kg/d, could be increased to a maximum of 10 mg/kg/d if thought to be clinically indicated. I published an abstract, and presented orally, at the PAS meeting in 2010, which showed that infants who got a higher dose, compared to controls who had a higher “dose of placebo”, had the same benefits on long term outcome that we saw among the overall group. To my shame, I never followed up and wrote up the full publication. But, as I was writing this post I dug out the powerpoint presentation that I gave in 2010 of this secondary analysis. I thought I would give you all a treat and show some of the results. We had 1583 infants with data for these analyses, and the medians for caffeine exposures are shown below:

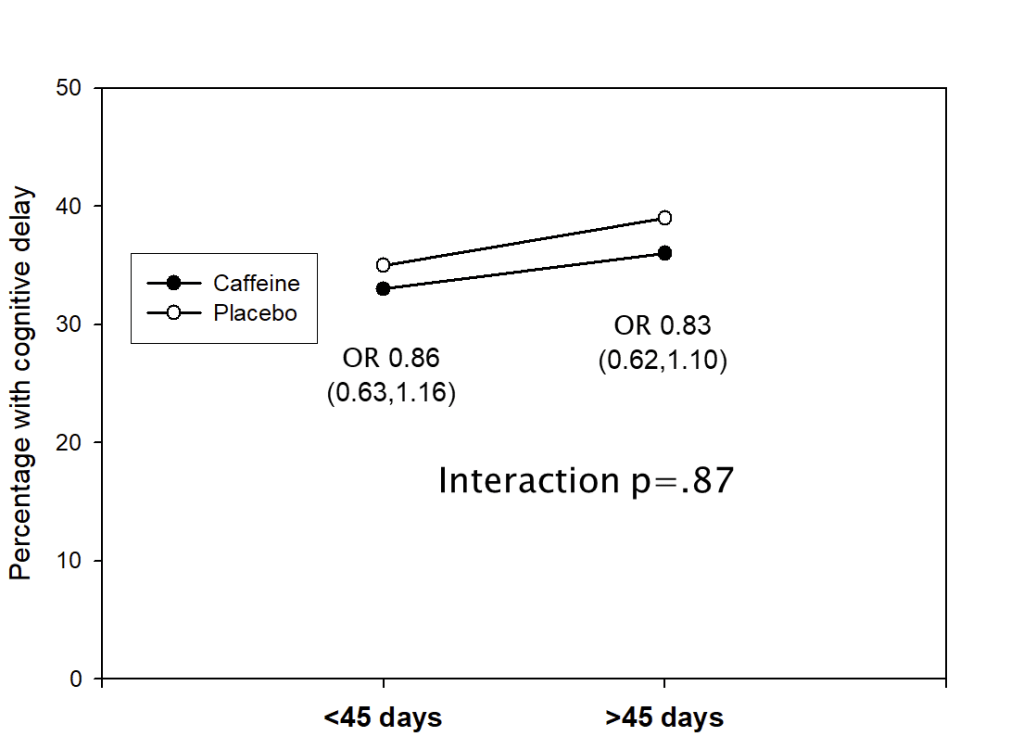

An example of the results is given below.

This shows the percentage of infants in each of the two groups who had a low Bayley (version2) MDI score, <85, at 18 months corrected age, divided by duration of treatment. Infants who had treatment longer than the median of 45 days, with either caffeine or placebo, were more likely to have low scores than those with shorter treatment. It also shows that the difference between caffeine and placebo groups was the same, regardless of duration of study drug administration. We did the same kind of analysis for maximum daily dose received, total accumulated dose, average daily dose, and the PMA at which caffeine was stopped. None of the analyses showed any impact of caffeine exposure on the advantages of the caffeine group. The ORs in the figure above are the Odds Ratios for “cognitive delay” between caffeine and placebo in the 2 subgroups.

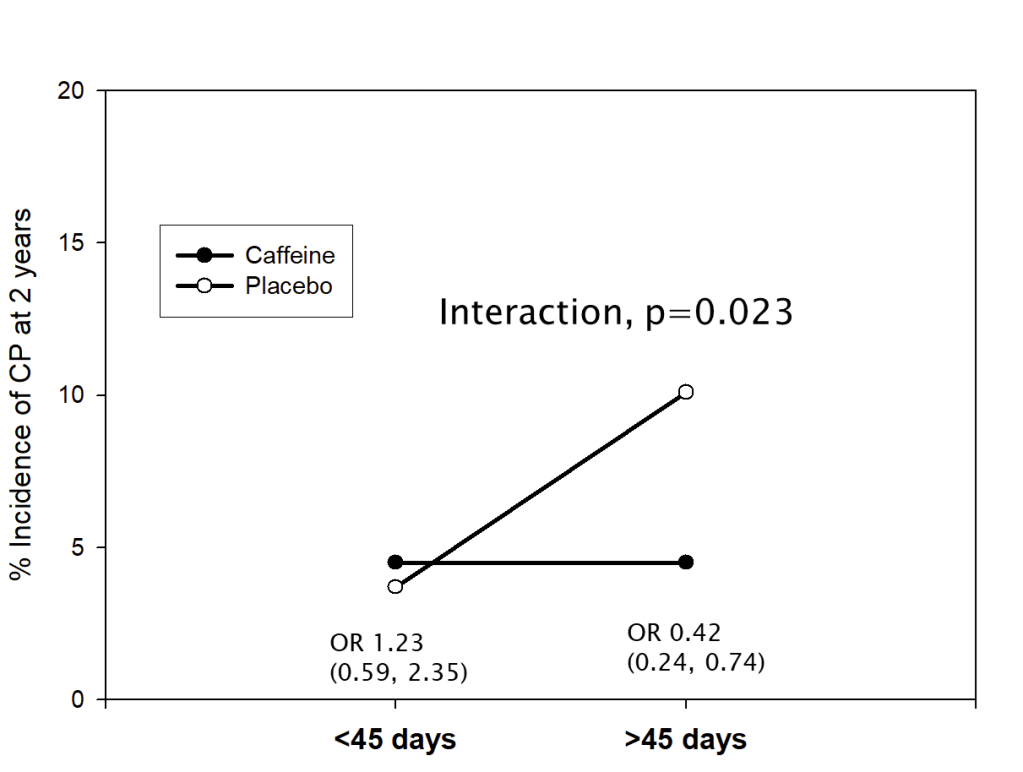

For the much smaller numbers with cerebral palsy, the results were different: longer duration of caffeine use, and higher total dose received were associated with a much greater difference between caffeine and placebo groups.

When we looked at average daily dose, or maximum dose received there was no association with the impact of caffeine on CP.

In other words, infants in the placebo group were more likely to develop CP (GMFCS grade 1 or worse) if they received study drug for longer than the median, but those who received caffeine were not. This made us wonder if the impact of caffeine on motor function was by different mechanisms to the impact on cognitive development. The overall primary outcome (which was “death or NDI”) was not associated with any of the metrics of caffeine exposure; the outcome, as usual, was driven by lower Bayley scores, so the impact of duration of therapy on CP was not noticeable in the composite primary outcome.

I must acknowledge the collaborators in the CAP trial here, the co-authors of that abstract were myself, Robin Roberts, Barbara Schmidt, Elizabeth Asztalos, Aida Bairam, Arne Ohlsson, Koravangattu Sankaran, and Alfonso Solimano, as well as the other CAP investigators; and of course the PI and driving force behind the trial was Barbara Schmidt. The title of the abstract was : The Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial: analysis of dose effects.

As I mentioned above, the enrolment criteria included use of caffeine to aid extubation, to prevent apnoea, or to treat apnoea. Some infants therefore received caffeine early as prophylaxis against apnoeic spells, others later after apnoea had become evident. Peter Davis led the group to publish a subgroup analysis, (Davis PG, et al. Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity trial: benefits may vary in subgroups. J Pediatr. 2010;156(3):382–7), showing that the subgroup who received caffeine for prevention of apnoea had fewer benefits, in terms of the long term advantages, than those who received it for treatment of apnoea or to assist in extubation. In contrast, the babies who received caffeine earlier (less than the median of 3 days of age) had more advantages than those who received it later (>=3 days), they had the biggest decrease in duration of oxygen treatment, and therefore in having a diagnosis of BPD, and more long term advantages.

The CAP study was performed in the days before we were so aggressive with non-invasive support, so large numbers of the early treated babies were intubated at the time they were enrolled. There is therefore some overlap with another secondary analysis in that paper, which was the impact of caffeine according to the respiratory support at the time of randomization. Intubated and CPAP babies had more benefit from caffeine than those not on any support.

As I was preparing this post I read a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis which purported to be an SR of prophylactic caffeine, compared to control groups. Miao Y, et al. Effect of prophylactic caffeine in the treatment of apnea in very low birth weight infants: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(1). It was, however, seriously flawed, and I won’t provide a link. The authors had included the CAP babies as if they had all received prophylactic treatment, and had also included, a second time, the babies in the CAP prophylactic subgroup from the Davis article, who were therefore double counted. That wasn’t all, 4 of the references in the reference list, supposedly to articles included in the SR, were not to the right articles, which meant that 4 of those that were actually included had no reference, and no way to find them, including one study (Ke H 2018) which apparently had over 1000 VLBW babies. A failure of peer review, I’m afraid.

A good quality SR, in comparison, is this analysis of caffeine and dose effects, on long term outcomes. Oliphant EA, et al. Caffeine for apnea and prevention of neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2024;44(6):785–801. The results of analyses for BPD, PDA, and survival, for caffeine compared to placebo, were almost entirely dependent on the CAP trial (weight of over 95%). When they analysed the dose comparison trials, higher doses led to less apnoea and less BPD.

Another reasonably good SR was a comparison of caffeine use by timing, early (<3 days) vs late (3 days or later). Karlinski Vizentin V, et al. Early versus Late Caffeine Therapy Administration in Preterm Neonates: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neonatology. 2024;121(1):7–16.It only included 2 small RCTs, each with about 90 subjects, so most of the data are from the 9 observational studies. All of the outcomes were better with early treatment, except for mortality. As the authors point out, mortality may be higher in the early treatment group because you have to survive at least 3 days to be in the late treatment group, i.e. there was a survival bias.

One study that will help a lot with the use of caffeine is the ICAF trial, which was presented at PAS in 2024, but has still not published their results. The intervention was restarting caffeine or placebo at 36 weeks, after the clinically used caffeine was stopped, until 42 weeks 6 days PMA. Outcomes were the number of Intermittent Hypoxia episodes, inflammatory markers, and MRI findings at about 45 weeks. It seems to be taking a long time to publish, as enrolment had already finished in June 2023. The initial sample size was planned to be 220, according to the registration documents, but only 160 were reported in the abstract. As it was an abstract there aren’t all the details about why the sample size was not achieved. Nevertheless, I think the benefits of continuing caffeine to 43 weeks that were reported are very interesting, and warrant a consideration of our usual approach. We could do with some more information, though, before prolonging caffeine for all babies <30 weeks. Are there risks of stopping caffeine at home after discharge? Are there benefits other than those reported, which have a clinical impact? The outcomes reported in the abstract are very interesting (go here for a review) there was much less intermittent hypoxia, but whether that translated into a useful clinical benefit is uncertain, what was an important benefit, however, was an 11 day shorter length of hospital stay. If that is due to the intervention, which seems probable, even though it was an “exploratory” analysis, then that is a potential major advantage of continuing caffeine much longer than we usually do.

The reason for ruminating about caffeine use is that we still don’t really know the optimal dose (perhaps higher doses would be better) the optimal timing (earlier may well be better, but the data are very weak) the optimal duration (longer might be better, ICAF will help, and hopefully there is along term outcome plan for the ICAF babies).

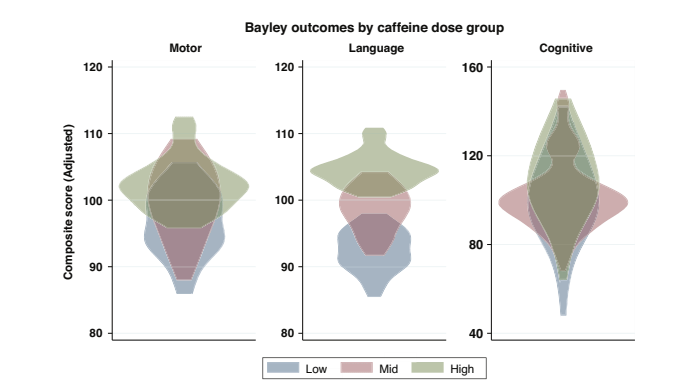

A new observational study (Ostrem BEL, et al. Cumulative caffeine exposure predicts neurodevelopmental outcomes in premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2025) examined the total dose of caffeine received in babies at UCSF. They calculated the average daily caffeine dose of a cohort of infants <32 weeks who had TEA brain MRI. Average dose was used to convert the babies into 3 tertiles of dose received, infants had Bayley version3 scoring at 30 months corrected age.

The infants receive a standard bolus dose of 20 mg/kg, the median maintenance dose was 7.6 mg/kg/d (IQR 6.3- 8.7) which is higher than the starting CAP trial dose, of 5 mg/kg. So, many of these babies had higher doses, with a range therefore between about 5 and 10 mg/kg. The 3 tertiles included 23 babies in each group. They also divided the total caffeine exposure by the number of days between birth and the due date, to give what they called average daily caffeine exposure. This averaged about 3.3, as it included a variable number of days that the infants received no caffeine.

As you can see from those violin plots, infants who had more caffeine had, in general, higher scores on motor and language domains, and slightly higher scores in the cognitive domain. The data were corrected for Gestational Age and duration of oxygen therapy. There was also, interestingly, very poor correlation between MRI findings and Bayley scores, which I will come back to in a future post.

These new data are again suggestive of a developmental benefit of caffeine in the long term, with infants receiving more caffeine having higher scores, after correction for potential confounders.

The major concern about higher standard doses that I have comes from the 1 trial which showed an adverse impact of very high doses. McPherson C, et al. A pilot randomized trial of high-dose caffeine therapy in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2015;78(2):198–204. In that trial the loading dose was a whopping 80 mg/kg, over a 36 hour period, compared to 30 mg/kg over 36 hours in the comparison group. Both groups received maintenance of 10 mg/kg/d. The high dose in that study led to more cerebellar hemorrhages on MRI, and had more abnormal signs at term, although longer follow up did not show a disadvantage of the high-dose group.

You may recall that the first neonatal comparison in the PLATIPUS platform is between 3 different caffeine dosing groups, with low dose being the standard of 20 mg/kg load followed by 10 mg/kg/d, medium dose being 30 mg/kg followed by 15 per day, and high dose being 40 mg/kg followed by 20 mg/kg/d. Treatment is up to 36 weeks followed by open label treatment according to the teams preference. The hierarchical composite outcome of that study should capture both the potential hazards suggested by the McPherson study, and the possible advantages of higher doses. Of course the optimal duration of therapy will remain uncertain until further studies similar to ICAF are performed.