There have been multiple publications concerning this issue recently, many from the tiny baby collaborative.

The first 2 publications are about the overall approach to providing intensive care at extremely low GA:

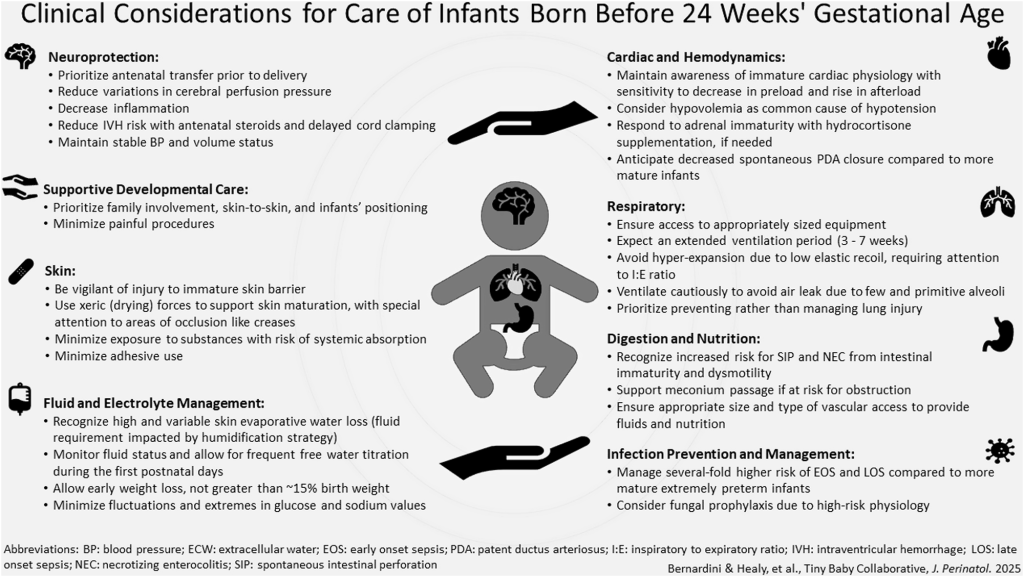

Bernardini LB, et al. It’s the little things. A framework and guidance for programs to care for infants 22-23 weeks’ gestational age. J Perinatol. 2025. This is a discussion of the many issues that should be addressed in centres trying to improve outcomes for these babies, including a recognition that they face specific challenges, require particular attention to detail, have unique physiologic limitations, and deserve an integrated caring approach with a committed team which includes obstetricians, nurses, all the allied health professionals, and parents. Indeed, despite the well-documented differences in the clinical approach of centres with good outcomes, one thing they all have in common is a belief that these babies can do well! You may have to convince your obstetricians that a delivery at 22 weeks is not a miscarriage, but is an extremely high-risk delivery that deserves the best possible care.

Many of the important considerations in this graphic are, appropriately, a bit vague. It is hard to disagree that maintaining “stable BP”, for example, is important, but exactly how to do that, and what to do when the BP is drifting downward at 4 hours of age, is beyond the scope of this graphic, and, unfortunately, has almost no evidence base to determine best practice.

Whatever you do, though, you should try to keep doing the same thing. Protocolized care (which means developing and following protocols) is essential in order to provide quality consistent care. (Al Gharaibeh FN, et al. The impact of standardization of care for neonates born at 22-23 weeks gestation. J Perinatol. 2025). This report from a health care regional program, treating 30,000 annual deliveries shows the results of the progressive implementation of a program to support the care of such babies. Guidelines covering many different aspects of care of these infants were implemented. In the early period, none of the 19 infants of 22 wk GA, and 39 of the 45 23-week infants received intensive care. This increased progressively to the post-implementation epoch to reach 29/34 and 48/51. For some reason these data are presented as Odds Ratios, which makes no sense to me when they are the result of an active decision. More importantly, survival improved, even when limited to the infants receiving active treatment, and complications of prematurity were stable or improved. Length of stay of infants receiving intensive care was shortened.

There are many publications documenting the efficacy of protocolizing complex care. The extremely immature infant is a prime example of a group who require such an approach.

Isayama T, et al. Survival and unique clinical practices of extremely preterm infants born at 22-23 weeks’ gestation in Japan: a national survey. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024;110(1):17-22 This paper is a good example of that premise, despite doing a lot of different things in different centres (some of which I would immediately label as “unnecessary”, “excessive” or even “dumb”), survival is very high. Japanese centres have strict protocols that all the staff follow, such that survival in this cohort at 22 weeks was 63% of those resuscitated (the majority) and at 23 weeks, 80% of those resuscitated (all except 2 of 757 infants). Among questionable practices in their protocols, 128 of the 145 level 3 centres in Japan perform echocardiography at least 3 times a day in the first 3 days, they measure a variety of different variables, as shown below, but what exactly they do in response to AV valve regurgitation, for example, is unclear.

116 of the centres also perform head ultrasound twice a day. What on earth you do about the head ultrasound result I also have no idea, especially as redirection of care is extremely uncommon in Japan.

Most of their ventilated babies are sedated with phenobarbitol or morphine, many also use fentanyl, even though it is useless as a sedative. 90% give probiotics, and some use donor milk if there is insufficient maternal milk. I was surprised to see that 50% give formula in this situation, but it seems to happen rarely in Japan, from other studies I have seen. Nearly all of them, 86%, give glycerine enemas in the 1st few days after birth, often on multiple occasions.

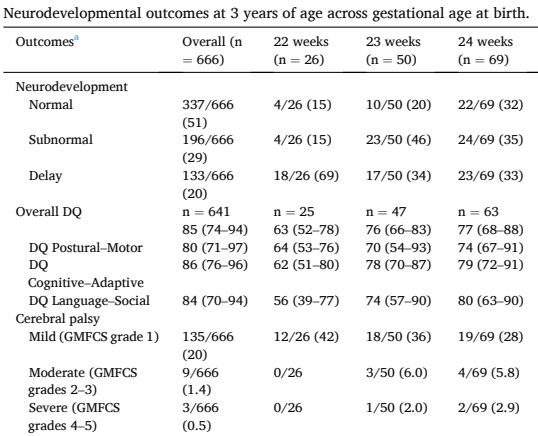

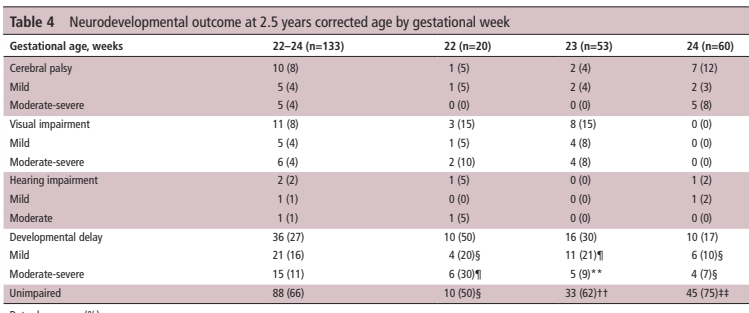

It is hard to argue with success, and the survival rates, of a largely unselected population are excellent. However, some of the longer term outcomes from Japan are concerning. This brand new publication, for example, (Haga M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for neurodevelopmental impairment in very preterm infants without severe intraventricular hemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia. Early Hum Dev. 2025;206:106286). Shows rather poor outcomes among the babies of 22 and 23 weeks, even though they are selecting, for this publication, the infants who do not have severe IVH or PVL. The results are not directly comparable to those from other countries as they use a Japanese evaluation tool, the Kyoto Scale of Psychologic Development, but the statistical spread of the results is similar to other tests, being normalised with a mean of 100 and an SD of 15. The following selection from their results includes the classification of the developmental test result first, with normal being >84, and delay being <70. You can see that the results are quite concerning at 22 and at 23 weeks; then, in the table, appear the actual mean scores and the incidence of CP.

This contrasts with outcomes from other places, such as these national data from Sweden, which include infants with brain injury on ultrasound (Soderstrom F, et al. Outcomes of a uniformly active approach to infants born at 22-24 weeks of gestation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021). Of note, not all these infants had formal developmental testing, but Moderate-Severe is similar to the “delay” in the above study.

It may be just my prejudices, but I like to think that the much less interventionist approach in Sweden, with fewer ultrasounds, and more focus on integrating parents, helps to lead to better long term development.

To go back to the obstetric part, the following article confirms the marked lack of evidence to support any intervention for the mother threatening delivery at 22 or 23 weeks. (LeMoine FV, et al. Considerations for obstetric management of births 22-25 weeks’ gestation. J Perinatol. 2025). The weight of the limited observational evidence is strongly in favour of steroid administration, however, and probably also magnesium sulphate.

Agren J, et al. Tiny baby math: supralinear implications for management of infants born at less than 24 weeks gestation. J Perinatol. 2025. This article is an explanation of the major impact of the tiny size of these patients on everything we do to them. The relative volume of fluid flushes leads to very high potential sodium administration rates and possible seriously excessive heparin doses. We need to develop better small equipment, be prepared to use 2.0 mm ETTs for example, and to reduce the volume of blood taken for lab testing, we can completely eliminate CRP testing for example (that’s my take, not theirs) and we can run electrolytes exclusively on the same whole blood sample that we use for the blood gas with no increase in volume (and also measure ionized calcium, glucose, lactate, total bilirubin).

Which brings us neatly to fluid balance management, firstly an analysis of current use of humidification (Stoll CM, et al. Approaches to incubator humidification at <25 weeks’ gestation and potential impacts on infants. J Perinatol. 2025) which shows that centres start at varying relative humidity, mostly over 75%, because there is no good evidence to decide what to start at, but that weaning can probably be quite fast. Using high humidity will help to avoid major trans-epidermal fluid loss, and the accompanying heat loss, from the latent heat of vapourisation (high-school physics!) and the consequent hypernatraemia.

That is confirmed by this study from Upssala (Naseh N, et al. Fluid Balance in Infants born at 22-23 Weeks’ Gestation: Trajectories and Associations with Outcomes. J Pediatr. 2025:114661), where they commence incubator humidity at 85%, and start IV fluids at 110 mL/kg/d at 23 weeks, or 120 mL/kg/d at 22 weeks. They adjust subsequently to aim for the following a) Maximum weight loss of 10–15% at a postnatal age of 3-5 days; b) Weight deficit of ~10% at 7 days, and regain of birth weight by 10–14 days; c) Plasma sodium <150 mmol/L; d) Initial sodium intake <4 mmol/kg/d. Which are similar to our goals, and I would think, many other centres.

I really don’t like the way this graphic is constructed, for one thing, I think the dotted lines, which are labelled as “Incidence (%)” are actually prevalence, i.e. the proportion of infants on that particular day with that diagnosis (if it was incidence it couldn’t go down again), and putting a continuous variable like weight loss on the the same graph as a discrete variable, like the proportion of a relatively small number of patients, which is then shown as a line, is really questionable. Acute Kidney Injury, here is defined by oliguria. Of the 69 included infants, 7 received insulin, the precise indications for which I couldn’t find, but there were more than 7 who had a blood glucose >20 mmol/L, so I presume it must be a persistent blood glucose >20.

As you can see from the error bars, weight loss of >15% was not rare, and was associated with increased mortality. They don’t mention IVH, but in our local data (which I haven’t yet published) the association of hypernatraemia (>145) with concurrent hyperglycaemia (>12 mmol/L) often led to severe hyperosmolarity, with peak osmolarity often >320, which was strongly associated with severe IVH.

Looking after these babies is a real challenge, many centres are now reporting survival at 22 weeks which is greater than 1/3, and in Japan is approaching 2/3, with dramatically better survival at 23 weeks, Compared to the rest of care for seriously or critically ill patients of other ages, that is very far from being futile! The quality of life of the large majority of survivors is excellent, even though many have challenges, in particular with speech development and executive function. Those challenges should be used as a lever to improve educational and other support services for these patients, not an excuse to deny them intensive care.

It seems that more and more centres are offering active intensive care to infants at these profoundly low gestational ages. I think it is often appropriate to give these babies a chance to “prove themselves”, but we must take into account other risk factors, in particular growth restriction and outborn status, which is often accompanied by lack of antenatal steroids, when we discuss the best approach with parents.

We owe it to these families to do everything we possibly can to improve their chances, with a dedicated team, who believe that these babies are worth the effort. A team which has examined the literature and their own practices in detail, have constructed clear protocolized care plans, and are prepared to follow them. Only then can these most immature babies get the care they deserve.

Great review of some of the most relevant recent papers. Completely agree with your final statement.

In Spain, the survival rates at 23w keep low (about 25%) and are <10% at 22w despite an increase of the intention to treat at 23w in last decade. Most centers are just in process of reviewing their guidelines and working on quality improvement projects. Usually, this extemely preterm infants born before 26w are icluded in the ‘less than 1000g’ or even ‘less than 1500g’ care guidelines. And they deserve separate guidelines and a stong collaborative effort between obstretical, neonatal and nurse teams.

Thank you Keith. Great review and absolutely agree.

I wonder if these centers caring for babies born at 22 weeks for many years do offer intensive care for these babies born in an outborn setting? Would you know.

Best,

Gabriel

I’m not sure, the best centres have good regionalization, and few hyperimmature outborns. But I’d be surprised if there was a blanket ban. Perhaps any readers can let us know