Several trials of liberal versus more restrictive transfusion practices have been published, and overall, it seems that being very restrictive in transfusions has no negative impacts on clinical outcomes, and depending on the trial, some positive benefits of avoiding transfusion.

One of the important studies of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group was the TRICC trial, which enrolled critically ill adults with a hemoglobin less than 9 g/dl, who were randomized to a target hemoglobin of 7-9 vs 10-12 g/dl. In that trial the adults with the lower target did better, with a lower in-hospital mortality of 22%, vs 28% with more liberal transfusion. In the results of that trial there was a suggestion of a different outcome in the subgroup with myocardial ischemia, so the group did another analysis in adults with cardiovascular disease, which showed no big differences in outcome, but still suggested a possible benefit of higher hemoglobin in those with unstable angina or an acute MI. Other studies have still, as far as I can see, not clearly answered the question in this subgroup of adults, and the most recent systematic review that I found basically stated “we don’t know”. As a result further trials are planned.

It could be that in patients with coronary artery disease, the ability to vasodilate and maintain myocardial oxygen delivery in the face of anaemia is limited, hence it is physiologically feasible that this subgroup would have different outcomes to those without serious coronary artery disease.

The same might be true for another subgroup, under-represented in the original TRICC and other trials, those with acute neurological injury. In this new trial in JAMA, adults with either traumatic brain injury, or a sub-arachnoid haemorrhage, or an intra-cerebral haemorrhage, who had a haemoglobin <9 g/dl, were randomized to a target of maintaining haemoglobin >9 compared to >7.

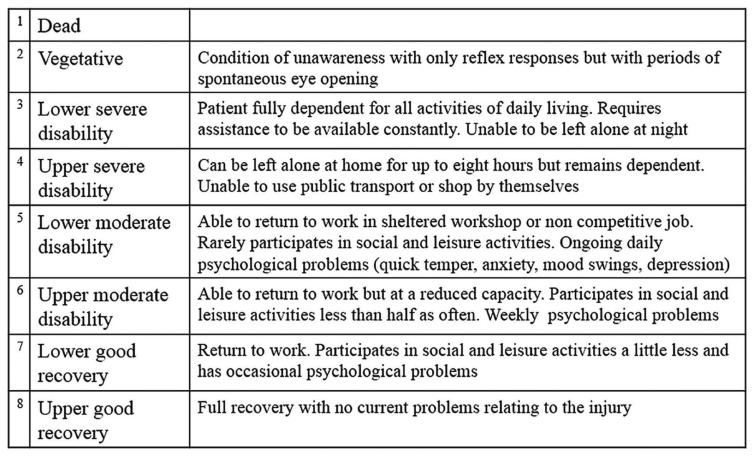

The rationale being that these groups of adults have a limited ability to increase brain perfusion in response to anaemia, and may benefit from higher haemoglobin, and that the previous studies have included very few such patients, and have also not measured longer term functional outcomes. The primary outcome of this trial was the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale after 6 months. We used a paediatric version of this scale in our recent publication (Boutillier B, et al. Survival and Long-Term Outcomes of Children Who Survived after End-of-Life Decisions in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Pediatr. 2023;259:113422. as it is a scale of functional capacities, in our study it was used in a descriptive fashion. In the new trial it was dichotomised into bad outcomes (1 to 5, 1 being death) and acceptable outcomes (6 to 8). The following table describes those scores

I will restrain myself from one of my usual rants about it being inappropriate to dichotomize continuous outcomes just for the simplicity of research design, or of equating death with being unable to use public transport! Designing and analyzing the trial using the GOS-E as an ordinal outcome would have been entirely possible.

800 patients, mostly in Europe and South America, were randomized, and outcomes were better in the higher hemoglobin group. The median GOS-E in both groups was 4, in other words large numbers of the patients had quite poor outcomes. As you can see from the graphical abstract above, the proportion with scores <6 was lower, 63%, with the higher HgB threshold compared to the higher threshold, 73%. When analyzed using an outcome of GOS-E<5, the higher HgB group still had an advantage, 50% vs 60%.

Why am I discussing this adult trial? I guess it is the first evidence, that I know of, that a higher hemoglobin threshold in critically ill patients improves outcomes. And that, in this group of patients we may have found the lower limit of acceptable HgB.

One thing we do not know in preterm babies is the extent to which they are able to vasodilate the cerebral circulation in the face of anaemia to maintain cerebral oxygen delivery. I guess this is why the people who designed the protocols that have been tested in neonatal transfusion trials have all used different thresholds during the first days after birth compared to later life. Or maybe it was just completely arbitrary!

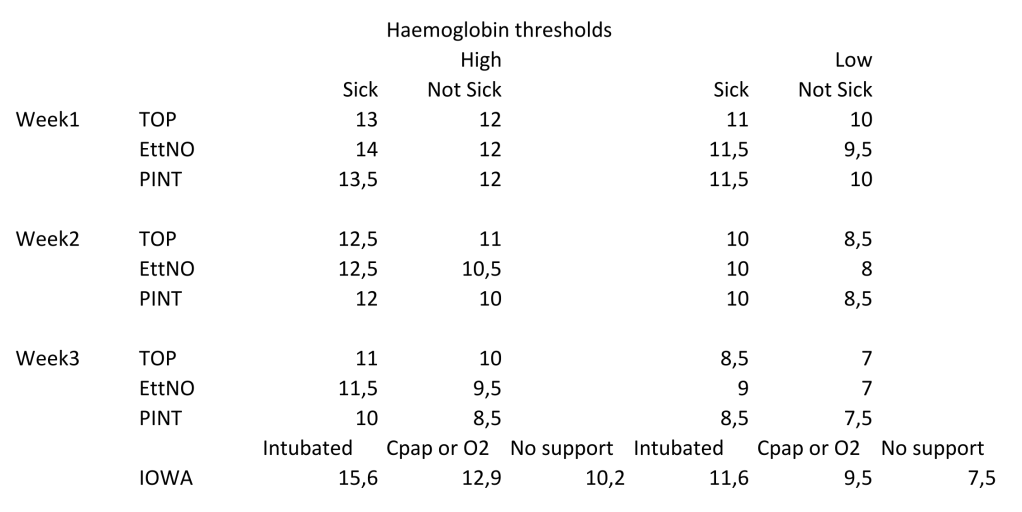

The neonatal trials which have been published, which I have discussed previously used the following transfusion thresholds (converted to Hemoglobin in g/100mL).

The definition of “sick” varied between the trials. In none of the trials was there any sign of harm from the lower transfusion threshold.

I think we are therefore probably well above the threshold of harm, but the new trial does show that under certain circumstances a higher threshold may be better, and that, at least in adults with acute brain injury, a higher threshold may improve outcomes.

Might this be true in preterm infants? I’m not sure if there has been any subgroup analysis of infants in the RCTs who had a brain injury, obviously the pathophysiology of such injuries is dramatically different in preterm infants than the adults in the new JAMA RCT, and the physiology of the control of cerebral perfusion is different also. But those results do suggest that we should consider the possibility that there is a lower limit to transfusion thresholds, which may differ among different groups of babies.