Sepsis caused by organisms transmitted during, or shortly before, labour is relatively uncommon in higher income countries with GBS screening programs; the incidence is now around 0.3 cases per 1000 live births, but varies, it may be as high as 10 times that, or as low as 0.1/1000. GBS remains the commonest organism, with E Coli close behind, followed by Strep viridans, and then a host of other bugs. Early identification and treatment is the key to good outcomes.

We can think of this in 2 ways; a risk of 1 case for every 2000 births is a very low risk. On the other hand it is an identifiable 72 hours of life with the highest incidence of sepsis that one will ever have! In general terms, about half of the cases have no identifiable risk factors, and about half the cases occur in babies with a risk factor or a combination of risk factors: chorioamnionitis (or “triple-I”); maternal fever; prolonged rupture of membranes; obstetric procedures; a previous baby with GBS.

Various groups have recommended evaluating risk factors at birth in order to determine the clinical approach to be taken. Usually that means that if the risk is considered high enough, then cultures are taken and antibiotics are given, even if the infant is currently well, or perhaps strict frequent physical examination. There may also be an intermediate group, who qualify for more intensive clinical monitoring, or perhaps for lab screening tests, such as a CBC and/or acute phase reactants, CRP, procalcitonin and others.

We should think of the risk-factor-based approach just as we would any screening test for determining interventions in healthy patients. What is the sensitivity, and specificity, and, depending on the incidence in your population, what are the negative and positive predictive values, of the risk factor combination?

Risk factors are often grouped in differing ways, which makes determining sensitivity etc complex, but given that about half of septic babies lack identifiable risk factors, usually sensitivity is around about 50%.

One study from the Netherlands compared the sensitivity of the Kaiser calculator with the 2021 NICE guidelines and the most recent Dutch guidelines. (Snoek L, et al. Neonatal early-onset infections: Comparing the sensitivity of the neonatal early-onset sepsis calculator to the Dutch and the updated NICE guidelines in an observational cohort of culture-positive cases. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;44:101270), in that study, at 4 hours after birth, the Kaiser calculator had a sensitivity of 36% compared to 50% for the Dutch, and 55% for the NICE framework, among the 88 patients eventually determined to have culture positive EOS. Other publications have shown sensitivity between 37% and 76% of the Kaiser calculator, with the CDC approach being reported to have a sensitivity between 50% and 100%. See reference list below. As the babies were followed, in the Snoek study, progressively more of them developed clinical signs satisfying treatment thresholds, so that 72% were eventually “screen-positive” by Dutch and NICE guidelines, compared to 61% by the calculator. What the publication never explains is how the remaining 24 babies were picked up. Did they become sick after 48 hours? Were they screened outside of the Dutch guidelines, and if so on what basis? Did they remain asymptomatic despite positive cultures?

Overall, the calculator and other risk-based systems, in very large cohorts with current EOS incidence, will, therefore, have around about 50% sensitivity within the first 4 hours after birth. In general, more sensitive risk-factor-based approaches will, of course, screen and treat many more infants. But specificity is more variable and difficult to calculate unless you are sure about the population frequency, but if we work with an incidence of 0.5 per 1000 live births, at term or near, and that risk factor screening tags 4% of babies as being at risk, then the specificity of screening calculates to 96%, with a PPV of 0.6 and a NPV of 99.9.

As always in epidemiology, if the risk factors are broader then the sensitivity will increase, and specificity will decrease. this is nicely illustrated by this figure from one of the studies of Escobar and Puopolo (and others), using just maternal risk factors. In this figure, higher risk at birth identified fewer cases (lower sensitivity) but had much higher specificity and fewer false positives. On the other hand it also demonstrates that the majority of EOS cases are NOT identified by their risk factors, sensitivity is <50% in the columns with intermediate and high risk of sepsis.

If we could define risk factors (or another screening test) that were more accurate, with a higher sensitivity AND specificity, then we could reduce both unnecessary intervention and false negatives. But as of now, about half of EOS cases will be among the babies that have a positive screening test result, and about half will be among the remaining infants, whether that screening test is the calculator or another one of the recent risk-factor-based approaches. The older standards were less specific, especially among babies born after chorioamnionitis, without being much more sensitive, which is why the calculator has led to a reduction in unnecessary treatment in most cohorts where it has been introduced.

For a screening test for an uncommon condition, a sensitivity of about 50% is pretty poor, and for any other condition we would probably abandon that approach! Imagine if our screens for hypothyroidism, or for PKU only had a sensitivity of 50%.

Can we make risk-factor-based screening more sensitive AND more specific?

The Kaiser EOS calculator, if strictly applied, usually ends up with about 4% of all babies receiving antibiotics. I have been trawling through recent literature (and there is a lot of it!) and, of unselected populations, the range of babies recommended to start or strongly consider antibiotics, is between 1 and 5%. That obviously also depends on the prevalence of the risk factors, one very important one being chorioamnionitis. Many guidelines that I have found steer clear of trying to define that phenomenon. They either leave it to individuals to decide whether there is a reliable history of chorio, or avoid the term and use maternal temperature instead. That widely-used Kaiser calculator doesn’t mention chorio, just highest maternal temperature. If you enter data into that calculator, the presence of a maternal fever of 39 degrees increases the risk of EOS by about 40 fold compared to a temperature of 37, depending on the other risk factors.

In contrast the NICE framework in the UK refers to a “clinical diagnosis of chorioamnionitis” but without diagnostic criteria; in full, the NICE list of antenatal risk factors is

- Red flag risk factor:

- Suspected or confirmed infection in another baby in the case of a multiple pregnancy.

- Other risk factors:

- Invasive group B streptococcal infection in a previous baby or maternal group B streptococcal colonisation, bacteriuria or infection in the current pregnancy.

- Pre-term birth following spontaneous labour before 37 weeks’ gestation.

- Confirmed rupture of membranes for more than 18 hours before a pre-term birth.

- Confirmed prelabour rupture of membranes at term for more than 24 hours before the onset of labour.

- Intrapartum fever higher than 38°C if there is suspected or confirmed bacterial infection.

- Clinical diagnosis of chorioamnionitis

The NICE guidance recommends cultures and antibiotics if you have one “red flag” or any 2 other risk factors. Which includes those antenatal factors, as well as the following list of clinical indicators

Red flag clinical indicators:

- Apnoea (temporary stopping of breathing)

- Seizures

- Need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Need for mechanical ventilation

- Signs of shock

Other clinical indicators:

- Altered behaviour or responsiveness

- Altered muscle tone (for example, floppiness)

- Feeding difficulties (for example, feed refusal)

- Feed intolerance, including vomiting, excessive gastric aspirates and abdominal distension

- Abnormal heart rate (bradycardia or tachycardia)

- Signs of respiratory distress (including grunting, recession, tachypnoea)

- Hypoxia (for example, central cyanosis or reduced oxygen saturation level)

- Persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborns

- Jaundice within 24 hours of birth

- Signs of neonatal encephalopathy

- Temperature abnormality (lower than 36°C or higher than 38°C) unexplained by environmental factors

- Unexplained excessive bleeding, thrombocytopenia, or abnormal coagulation

- Altered glucose homeostasis (hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia)

- Metabolic acidosis (base deficit of 10 mmol/litre or greater)

Why have I come back to this issue after 2 other recent blog posts? It’s because of the publication of new Swiss guidelines (Stocker M, et al. Management of neonates at risk of early onset sepsis: a probability-based approach and recent literature appraisal : Update of the Swiss national guideline of the Swiss Society of Neonatology and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Group Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr. 2024. That guideline includes the following table which includes antenatal risk factors.

As you can see the Swiss don’t refer to chorioamnionitis at all, but use the ACOG/AAP term of triple I, which stands for “Intrauterine Infection or Inflammation…. or both” and give some criteria for that diagnosis. My only quibble with this list is that Elective Caesarean without labour or ruptured membranes has a zero, rather than low, probability of EOS, and should be listed as a contraindication to doing a sepsis workup!

Once an at-risk patient is identified, the Swiss guideline recommends Serial Physical Examination, SPE. And here it starts to get questionable, for me. For the Swiss guideline that apparently simply means vital signs q4h, which they specify as being heart rate, temperature, peripheral perfusion and skin colour. Exactly how this is meant to be done, by whom, and with what criteria, are not specified; what exactly is meant by “peripheral perfusion”, for example? If this is going to be done for thousands of babies, it is vital that it is clear and unambiguous. As I understand it, babies with a low probability of sepsis should have routine care, which, I suppose therefore, must exclude q4h vital signs.

However, the references that they give to support the SPE approach have all used very different approaches. For example, here is a figure from an Italian group (Berardi A, et al. Serial physical examinations, a simple and reliable tool for managing neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis. World J Clin Pediatr. 2016;5(4):358-64) that have published about their approach a few times. As you can see, they immediately culture everyone with “chorioamnionitis” or intrapartum fever, and, for the remaining at-risk infants, do the SPE on multiple occasions, “in turn by bedside nursing staff, midwives and physicians” using a purpose built form, shown here. The methodology and timing of the SPE is vitally important.

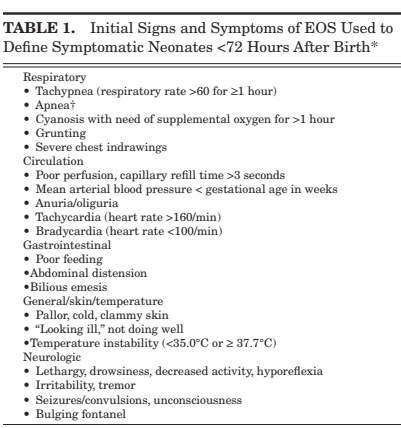

The group from Stavanger, Norway, (Vatne A, et al. Reduced Antibiotic Exposure by Serial Physical Examinations in Term Neonates at Risk of Early-onset Sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(5):438-43) have also published widely on this issue, their protocol is for hourly structured examination, of infants deemed at risk, by the nursing staff for 24 to 48 hours, recorded on a special form, and taking note of the signs shown in the figure below. As far as I can tell, they did not routinely treat infants with antenatal chorioamnionitis or intrapartum fever, but used the same approach for them also.

Among the 8000 babies analyzed using this approach, there was 1 true, culture-positive, sepsis (and supposedly 55 “culture-negative sepsis”), and about 1% of infants treated with antibiotics; with no deaths due to sepsis.

The group in Stanford Joshi NS, et al. Clinical Monitoring of Well-Appearing Infants Born to Mothers With Chorioamnionitis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172056 have a different approach again, they directly observed the baby with risk factors for 30 minutes, then, in an initial phase, admitted them to the level 2 nursery on a cardiac monitor with q4h vital signs for 24 hours minimum, then transferred to maternal/infant care thereafter. In the second stage of their project, the infants went directly to maternal/infant care, and had “vital signs and clinical nursing assessments with documentation in the electronic health record at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes and then every 4 hours for the first 24 hours after birth. After 24 hours of age, vital signs and clinical nurse assessments were performed every 8 hours until discharge. Nurse staffing ratios for all neonates in couplet care in the postpartum unit were 1:3”. The Stanford experience in that 2018 publication only included 277 infants, all of whom were exposed to “chorioamnionitis”. They showed that their approach was safe, but there were 0 cases of culture-positive sepsis, so again, I could suggest that ANY approach would have been safe!

In a much more extensive report from Stanford from 2020, there were 20,000 infants, with 6 cases of GBS sepsis, no other culture positive sepsis (and one probable CSF contaminant with 2 coagulase negative staph species). It seems that all their newborn babies are monitored in the same way, regardless of any risk factors, with the vital signs recorded at those same intervals and a 1:3 nursing ratio, for the 1st 24 hours of life. Despite the reliance on SPE, they still treat about 4% of all the term and near-term infants with antibiotics; or about 150 babies treated for every true case.

In Lausanne (Duvoisin G, et al. Reduction in the use of diagnostic tests in infants with risk factors for early-onset neonatal sepsis does not delay antibiotic treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w13981) they have done things differently again, in 2 different time periods they first did the following “Vital signs were checked by midwives every 4 hours during the first 24 hours and every 8 hours during the next 24 hours in all infants with risk factors for EOS” during that period they also did CBC and CRP in all the babies with risk factors. During period 2 “in addition to the monitoring of vital signs by midwives, infants with risk factors for EOS were examined by paediatric residents every 8 hours during the first 24 hours” but they stopped doing the routine CBC and CRP.

In Lausanne, there were 11,000 babies in their report, with only 3 proven infections, which were all in the 6000 infants in the first period. None among the 5000 in the second period. Which is an example of why these decisions are so difficult to make. In the second phase of their study they could have done nothing at all, just sent all the babies home without ever examining them, and treating none of them with antibiotics, to make a silly suggestion, but as there were no culture-positive cases of sepsis in 5000 babies during that period, the results would, I propose, have been just as good! About 2% of all babies born received antibiotics.

When neonatal sepsis is so uncommon, at less than 0.5 cases per 1000 live births, we need enormous studies to prove the safety of one approach over another.

In order to really determine the risk/benefit balance of any particular approach, we need to know the real risks of each approach, with the major benefit, of course, being that we prevent death or serious illness from EOS. But, even that benefit is difficult to determine.

Imagine a well-appearing baby with enough risk factors to receive immediate antibiotics by the EOS calculator, but the baby is treated in a centre using an SPE approach without immediate antibiotics. The infant then develops a serious illness at 6 hours of age, and has a culture and antibiotics; how should that be counted? Is that a success of the SPE approach, or an unnecessary clinical deterioration? We cannot just look at sepsis related mortality, as that is extremely rare, and most of the cohorts have between 0 and 1 death.

If we use a risk-factor based approach, which identifies around 6% of babies as being at risk of EOS, and includes about half of the cases, in a population with an EOS incidence of 0.4 per 1000 the incidence among the 6% at risk will be about 0.3%; among the remaining 94% of infants EOS incidence will be 0.2 per 1000. The Kaiser calculator refines this further, dividing into a category at highest risk, including about a quarter the EOS cases. Which means that there are 1.5% of babies at highest risk, and among them the incidence of EOS approaches 1%.

The question then becomes almost philosophical, should we culture and treat those at highest risk, with the hope of preventing deterioration, but with the knowledge that 99% of treated babies will not be infected, and will have the pain, the adverse impacts on parental infant interaction, and the dramatic, long-lasting effects on the intestinal microbiome.

We also cannot eliminate the risk of EOS and a later deterioration among screen-negative babies, so must ensure adequate parental education, and some sort of surveillance of even low-risk babies.

Perhaps the best approach would be to ensure intensive clinical surveillance of the 1 to 2% of infants who are highest risk, in a way which has the least adverse impact on the infant and the family; an intermediate form of surveillance for the 4 or 5% who at intermediate risk, while ensuring that the system is fail-safe, and babies are not missed. But we must not forget the remaining 95% of infants among whom half of the EOS cases occur, and ensure some form of surveillance for that group with an incidence of maybe 0.1 per 1000. Whether that should include occasional nursing evaluation, parental education, increased sensitivity to the problem of the population at large, or some combination, I do not know. I don’t think it is feasible in most health care systems to follow the Stanford approach of “enhanced clinical monitoring” in all newborns, with frequent vital signs, nursing examinations and 1:3 nurse to baby ratio. Creating the right safety net for low risk babies will detect as many cases as screening or SPE among the high risk.

Additional References (without URL links, I ran out of steam!)

Gyllensvard J, et al. Antibiotic Use in Late Preterm and Full-Term Newborns. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243362.

Kuzniewicz MW, et al. Update to the Neonatal Early-Onset Sepsis Calculator Utilizing a Contemporary Cohort. Pediatrics. 2024;154(4).

Dimopoulou V, et al. Antibiotic exposure for culture-negative early-onset sepsis in late-preterm and term newborns: an international study. Pediatr Res. 2024.

Harrison ML, et al. Beyond Early- and Late-onset Neonatal Sepsis Definitions: What are the Current Causes of Neonatal Sepsis Globally? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Evidence. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2024.

Achten NB, et al. Sepsis calculator implementation reduces empiric antibiotics for suspected early-onset sepsis. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(5):741-6.

Coleman C, et al. A comparison of Triple I classification with neonatal early-onset sepsis calculator recommendations in neonates born to mothers with clinical chorioamnionitis. J Perinatol. 2020.

Morris R, et al. Comparison of the management recommendations of the Kaiser Permanente neonatal early-onset sepsis risk calculator (SRC) with NICE guideline CG149 in infants >/=34 weeks’ gestation who developed early-onset sepsis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020:fetalneonatal-2019-317165.

Goel N, et al. Screening for early onset neonatal sepsis: NICE guidance-based practice versus projected application of the Kaiser Permanente sepsis risk calculator in the UK population. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019.

Sloane AJ, et al. Use of a Modified Early-Onset Sepsis Risk Calculator for Neonates Exposed to Chorioamnionitis. J Pediatr. 2019;213:52-7.

Gong CL, et al. Early onset sepsis calculator-based management of newborns exposed to maternal intrapartum fever: a cost benefit analysis. J Perinatol. 2019.

Carola D, et al. Utility of Early-Onset Sepsis Risk Calculator for Neonates Born to Mothers with Chorioamnionitis. J Pediatr. 2017.

Hi Dr. Barrington,

Thank you for this wonderful review of the current evidence on EOS approaches in late preterm and term neonates and the challenges from a numbers standpoint of any decision framework when dealing with such a rare disease.

Just to provide a bit more clarity on the Stanford approach and our ‘safety net’. The nurse to neonate ratio of 1:3 is for couplet care (mother and baby) so this is an actual nurse to patient ratio of 1:6. I think this is becoming more and more common and even standard of care including in British Columbia.

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/minimum-nurse-to-patient-ratios/mnpr_maternity_unit.pdf

https://www.awhonn.org/education/staffing-exec-summary/

We also have one of the highest pregnancy case mix indexes in the U.S. with >60% of delivering mothers considered high risk. Yet, we still find ‘enhanced clinical monitoring’ with q4h vital signs and standard nurse assessments over the first 24hours quite feasible. We hope others can too. Just feels to us part of good newborn care at this point.

Warm regards.

Adam

Stanford University