I usually try to avoid buzz-words and phrases like “paradigm shift” but it applies well, I think, to what is happening in the world of neonatal follow-up, and more broadly, I hope, to neonatal research as a whole.

Neonatologists were pioneers in the development of outcome research (Barrington KJ, Saigal S. Long-term caring for neonates. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11(5):265-6), when we started saving babies who would have universally died in the past, we wanted to know how they would turn out, and what kinds of lives they would have. Follow-up clinics developed with a dual mandate, to ensure that ex-preterm infants were evaluated and to co-ordinate any care they required, and to measure and collate their outcomes for quality control and research.

We used measures that were available, and we have gradually developed an almost universal approach, focusing primarily on brain injury, with standardized screening for developmental problems, neurologic exams to identify motor dysfunction, and hearing and vision screening. Other domains which have an impact on families after discharge have been less well evaluated, such as behaviour, feeding issues, sleep, pulmonary symptoms.

Developmental screening tests of various types have been used, and in, most of the world, the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) have become the default developmental screening exam. Despite what you might think, if you have read these blogs for a while, I actually think that developmental screening is a good thing! Some sort of universal screening for developmental issues is important to identify infants having difficulties, and ensure that they can receive any intervention that they need. What I am very opposed to is the simplistic dichotomising of outcomes into “impaired” if the score is less than 85 (and severely impaired if it is less than 70), and “non-impaired” if the infant gets 85 or more! Even worse is compounding low developmental screening test results with death, to give the dichotomous outcome of “death or NDI”.

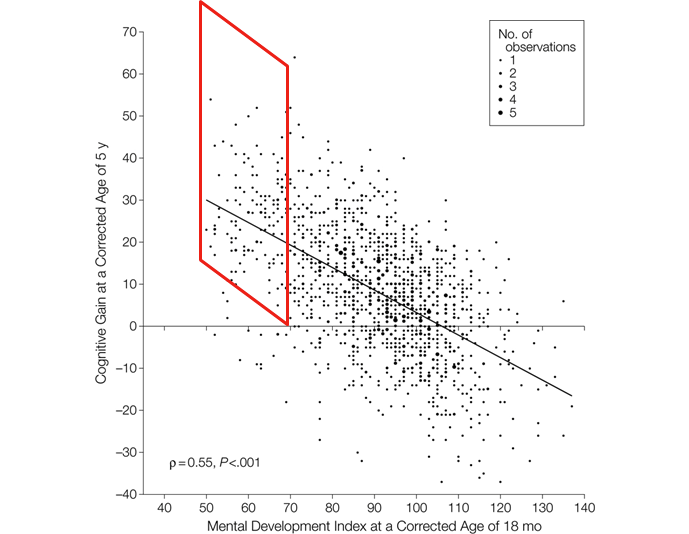

I am now not even sure what to call a low BSID score. I have frequently referred to this as “developmental delay”, however, I have heard that some parents dislike this term as it implies that the infant will catch up. While this is true for large numbers of infants, it is not universally the case. We showed in the CAP cohort that only 18% of babies with a 2 years BSID score more than 2 SD below the mean had a 5 year IQ >2 SD below the mean. (Schmidt B, et al. Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. JAMA. 2012;307(3):275-82.Manley BJ, et al. Social variables predict gains in cognitive scores across the preschool years in children with birth weights 500 to 1250 grams. J Pediatr. 2015;166(4):870-6 e1-2).

This figure is from the first of those publications, with the red parallelogram I added to include all the babies who had an 18 month BSID <70, but had a 5 year IQ >70, the differences between the 2 scores we referred to as “cognitive gain”. As you can see, many babies with BSID version2 MDI scores considered to be impaired had normal IQ, or even above average IQ, once they reached 5 years. Only the few beneath the red shape still had IQ >2SD below the mean. Perhaps we should just call a low BSID, or other similar test, score “LDSTS” a low developmental screening test score, that, I think would emphasize the ridiculousness of equating death with low BSID scores, and cerebral palsy and visual or hearing problems. It doesn’t lend itself to a snappy acronym however, “NILDSTS” (neurological impairment or low score on developmental screening test) hardly trips off the tongue.

When I review the literature about the predictive ability of the BSID (whichever version) for later outcomes, many publications have reported that the BSID have a statistically significant correlation with later outcomes, but few have really evaluated the predictive value of the BSID for later outcomes. It is hardly surprising that a screen for developmental problems will be statistically correlated with later IQ tests. But whether the developmental screen is individually useful as a predictor of the likelihood of intellectual impairment is a totally different question! Publications often include statements such as, in this interesting publication among preterm infants, “there was a highly significant correlation between language scores at 2 years and later literacy skills”, but they usually do not continue with what this study showed “language development at 2 years explained 14% to 28% of the variance in literacy skills 5 years later”.

To make sure that is clear, there was a significant correlation between scores on the developmental screening test and later abilities, but that correlation explained only a very small part of the later outcome. The same has been shown with other domains of the screening tests, especially cognitive. Motor development scores tend to be more predictive of later motor outcomes.

I think of this as a similar issue to the value of pre-discharge MRI in preterm infants. Overall, in large groups of babies, more MRI-visible brain injury is correlated with poorer developmental and later intellectual outcomes. Which is not the same thing as showing that a pre-discharge MRI is of value to the individual. The individual predictive ability of almost any finding on an imaging study (MRI or ultrasound) for the outcomes we usually measure is between low and very low. Of course, there are exceptions, extensive bilateral cystic PVL is very highly predictive of Cerebral Palsy, for example, but most other findings have very limited predictive value. (Chevallier M, et al. Decision-making for extremely preterm infants with severe hemorrhages on head ultrasound: Science, values, and communication skills. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;28(3):101444).

To get back to the “Paradigm Shift” I mentioned, all of the previous discussion in this post has been about outcomes that we currently measure, BSID, Cerebral Palsy, etc. which, as the Parents’ Voice Project has shown are of limited interest to parents (Jaworski M, et al. Parental perspective on important health outcomes of extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022;107(5):495-500). We are shifting, perhaps all too slowly, to a new paradigm, an emphasis on outcomes that are of importance to families.

A national group of investigators and parents have been working together in Canada to develop both a catalogue of outcomes that are important to parents, and to decide how best to measure and collect the data. That process is described in a new article just published in Pediatrics, with a parent and a physician investigator as co-first authors! Pearce R, et al. Partnering With Parents to Change Measurement and Reporting of Preterm Birth Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2024. (Although I was not an author of this article, you will see I am named as a member of the Network).

The publication is a clear description of the needs, and challenges, in preterm follow up, and how the network is addressing them. We really need better data about outcomes of preterm infants, measuring things that matter to families, in order to be able to intervene, research, and counsel parents.

Let’s shift that paradigm!