I wrote a similarly titled post 3 years ago, which lamented the poor research practices of a group in Zhengzhou, who seem to perform large RCTs, then register them after completion, and sometimes register them with different primary outcomes to those which are then published. They often publish the articles in strange journals that rarely publish large clinical RCTs, journals which are often supposed to have editorial practices which do not allow the publication of retrospectively registered RCTs, but which publish them nonetheless.

I bring this up now because of my series of posts on NEC prevention, and the publication last year of a systematic review of erythropoietin prophylaxis for preventing NEC. (Ananthan A, et al. Early erythropoietin for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates – an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(5):1821-33). That review showed, when including all the published data, a major, 23%, reduction in NEC with erythropoietin prophylaxis. However, when eliminating the retrospectively registered trials, there was no longer a clear effect, although a 50% reduction would still be within the confidence intervals of the meta-analysis.

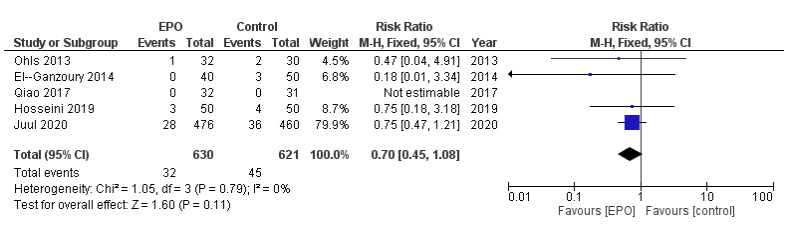

Here is their Forest plot, from the on-line supplement, of the effects of prophylactic Epo vs control on the incidence of “definite NEC” that is grade 2 or 3, only including the prospectively registered trials

And here is their plot including all the RCTs

As you can see, the only individual trial which shows a reduction in NEC which is not likely due to chance is Wang et al, who had a very high incidence of NEC among their babies, with a mean GA of 30 weeks the controls had 17% NEC, with 5.4% stage 2 and 3 NEC. Among their subgroup of <28 weeks gestation 17% had grade 2 or 3 NEC in the controls. In comparison Juul et al report a control incidence of NEC of 8% among infants with a mean GA of 26 weeks.

Since that previous post the same group has published another retrospectively registered trial from some of the same institutions, with overlapping dates and overlapping eligibility criteria to the “epo for prevention of NEC trial”, the new trial is Song et al 2021, with the reference details below.

I wrote to the editors of the 2 journals which published the articles referenced below, pointing out the overlaps. This is an extract of that email:

Song J, Wang Y, Xu F, Sun H, Zhang X, Xia L, et al. Erythropoietin Improves Poor Outcomes in Preterm Infants with Intraventricular Hemorrhage. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(6):681-90.

Wang Y, Song J, Sun H, Xu F, Li K, Nie C, et al. Erythropoietin prevents necrotizing enterocolitis in very preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):308.

The two trials were performed by researchers mostly based in Zhengzhou, who have previously published an article on a related subject which was performed in 2009 to 2013 and retrospectively registered in January 2014 (Song J, Sun H, Xu F, Kang W, Gao L, Guo J, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin improves neurological outcomes in very preterm infants. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(1):24-34). NCT02036073.

The two new trials enrolled babies of less than or equal to 32 weeks gestation, between January 2014 and December 2017 in the case of Song et al “in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the Third Affiliated Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University”, and between January 2014 and June 2017 for Wang et al in “four centers including the Third Affiliated Hospital, Children’s Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and the Women and Children Health Care Center of Luoyang”.

As far as I can see, therefore, there are 2 NICUs, at the Third Affiliated Hospital in Zhengzhou, and the Children’s Hospital of Zhengzhou, which were recruiting to both trials over the same period.

The eligibility criteria for the 2 trials were similar except with regard to the results of head ultrasounds performed before 72 hours of age. In Song et al, only infants with Intraventricular Hemorrhage, of any grade, were included. In Wang et al infants with the more severe grades of hemorrhage were excluded, that is grade 3 and 4 hemorrhage. Thus, infants with grades 1 and 2 hemorrhage would have been eligible for both trials.

The CONSORT flow chart for Song et al notes that there were 370 infants with IVH admitted to the 2 enrolling NICUs during the period of the study, of whom 316 were randomized. According to table 4 in that publication there were 20 infants with the more severe grades of hemorrhage included in the trial.

The CONSORT flow chart for Wang et al reports that of 1327 infants assessed for eligibility, only 9 did not meet inclusion criteria (which should, therefore, include any babies with grade 3 and 4 hemorrhage) and there were 1285 babies randomized. There should therefore, according to Wang et al be a maximum of 9 infants with grade 3 and 4 hemorrhage across the four NICUs, but according to Song et al there were 20 in two of the NICUs.

There appear to have been 296 infants admitted to an NICU at the two hospitals involved in Song et al’s trial with grade 1 and 2 hemorrhage during the period January 2014 to June 2019. Over the same period 1285 infants were enrolled in those 2 hospitals and 2 other hospitals in a completely different trial with a different primary outcome. The 296 infants in Song’s trial would have been eligible for the Wang et al trial but are not mentioned in the Wang et al manuscript nor in their CONSORT flow chart.

Both trials were retrospectively registered after completion; NCT03914690 and NCT03919500 were registered within 2 days of each other in April 2019.

I believe that my observations raise serious questions about the research design, research ethics and publication ethics behind these publications. It seems that either there were substantial numbers of infants enrolled in both of the trials, or the CONSORT flow diagrams are inaccurate; there are, of course, other potential explanations.

Additionally, there are major problems with reporting within each of these manuscripts.

Song et al report none of the short-term outcomes reported as a routine in neonatal trials involving very preterm infants. They report a mortality of 25 infants of the 316 enrolled, a survival of over 92% of a group of infants with a mean gestational age of 30 weeks is remarkable.

The authors do not report the frequencies of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, later serious brain injury on ultrasound, necrotising enterocolitis or late onset sepsis, all of which have major impacts on long term developmental outcomes. In order to determine the potential impacts of this prophylaxis in another group of very preterm infants, data regarding those other diagnoses is essential and should have been included in this manuscript.

The editor-in-chief of CNS drugs wrote back a few days ago, Sue Pochon is an employee of Springer Nature who appears to have no medical training, indeed her Linked_In profile shows that until 2001 she was catering manager at the Pirate Inn. She may well be an excellent manager, but I wonder if she has any idea of the importance of large RCTs in preterm infant showing an apparent major impact on NEC, and enormous apparent impacts on the developmental outcomes of the babies. The journal “CNS drugs” publishes a small number of articles each month, 6 or 7 usually, the large majority of which seem to be review articles, some systematic reviews, and a few observational studies. With a brief search I wasn’t able to find any other large RCTs, just one or two pilot trials. Unfortunately, their “instructions to authors” shows that they will accept retrospectively registered trials.

In her reply to me she notes that there was an investigation of my concerns and states “Fortunately, we have been unable to identify any fraudulent activity. While the trial dates do indeed overlap, we are satisfied that the trial participants were different, as were the trial outcomes, and that such concurrent studies are entirely feasible given the size of the recruiting hospitals.”

I had not, in fact, accused the authors of fraudulent activity. Rather that there were serious concerns, and that the CONSORT diagrams cannot be accurate. Either there were some babies whose data is included in both trial reports, or there are babies who were ineligible for one of the trials because they were enrolled in the other. Of note, the intervention in the 2 trials was identical (500 IU EPO/kg i.v. every 48 hours for 2 weeks) and controls received a saline placebo, even though they were not blinded studies.

The newer publication (Song et al, CNS drugs 2021) does include a very brief mention of some other clinical outcomes, such as a few cases of NEC in their babies, without specifying the grade of NEC, 11/159 [6.9%] in controls, vs. 9/157 [5.7%] in Epo babies. They also mention ROP being slightly lower, without specifying what stage, and BPD being significantly lower, without referring to any definition. According to the results of that trial, there was a dramatic effect on low Bayley (version 2) scores, with a more than 50% reduction in the proportion of babies with MDI <70, from 15% to 7%. They also show less CP, a reduction from 6% to 3%.

The whole point of registering a trial is to ensure that the sample size was calculated beforehand, that the primary, and main secondary, outcomes were decided before the data accumulated, and that the procedures were protocolized prior to performing the trial. With retrospective registration all this is lost. There is a risk that the primary outcome was chosen after examining the data, and/or that the study was terminated early when a potentially spurious outcome appears different between groups; both of which dramatically increase the chances of a type 1 error. These researchers have clearly been aware of the necessity of registering trials for many years, so they cannot even claim ignorance.

Journals should stop accepting retrospectively registered trials, they are unreliable sources of data that skew the medical literature.

The systematic review of erythropoietin for NEC prevention (referred to above) shows that it is indeed possible that Epo decreases NEC; the confidence intervals, even when the retrospectively registered trials are excluded, include a possible major reduction in NEC of 50%, largely based on the 25% reduction in grade 2 to 3 NEC shown by PENUT. This suggests to me that we need another large trial, focusing on NEC reduction, of prophylactic Epo. Apart from gestational age, there are few additional risk factors for NEC; early onset sepsis being one, but I don’t think you could do a trial just enrolling babies with EOS.

Any future RCT of NEC prophylaxis must be prospectively registered, with clearly defined primary outcomes, and eligibility criteria, and a report of the desired sample size.