Many of my readers will remember the impressive results of the high-quality study by Paolo Manzoni, Manzoni P, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of late-onset sepsis in very low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302(13):1421–8) which showed that routine supplementation of preterm infants with bovine lactoferrin (bLF) dramatically reduced late-onset sepsis.

Many of us were quite excited with this finding, and launched our own studies, I performed a pilot in my NICU, hoping to use the data to get funding for a confirmatory trial (Barrington KJ, et al. The Lacuna Trial: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot trial of lactoferrin supplementation in the very preterm infant. J Perinatol. 2016;36(8):666–9), and at about the same time ELFIN was started in the UK. LIFT then took place in Australia/NZ, and, more recently, a Canadian version of LIFT was performed to increase study numbers and power.

Unfortunately all of the large confirmatory studies have been completely null, without a hint of a benefit. Including LIFT-Canada, which is in submission so I won’t go into any details, but I can say that we did not show a benefit of bLF.

There continue to be some trials which do seem to show an effect of bLF, including this very new trial (Plaza-Astasio V, et al. Preventing Sepsis in Preterm Infants with Bovine Lactoferrin: A Randomized Trial Exploring Immune and Antioxidant Effects. Nutrients. 2025;17(19)). Just over 100 VLBW infants were randomized to bLF supplementation or control, prior to 72 hours of age, and followed for LOS, as well as lab tests of antioxidant and immunologic effects. LOS was defined as “Laboratory confirmed sepsis” after 72 hours. The authors followed the NeoKisses definitions, which, as far as I can tell, include so-called “clinical sepsis” without a positive blood culture, but in the supplementary materials of this new study there are the same number of organisms listed as the episodes of sepsis, that is 11 in the bLF group and 21 in the placebo group. In other words they showed a reduction in culture-positive sepsis.

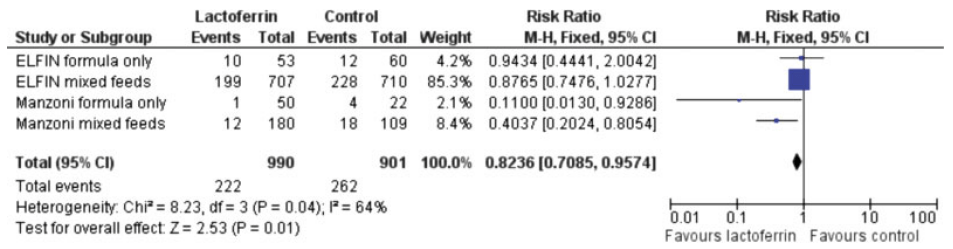

The authors note that their breast feeding rates were lower than some of the other large trials, at around 75% compared to over 90% in the large trials, and suggest this as a possible explanation for the difference of their results compared to the larger RCTs. That seems to me doubtful, if bLF was only effective in formula fed babies, then they could not have shown such a large decrease. Ochoa and her collaborators have published an IPD meta-analysis of the VLBW infants enrolled in their 2 trials (see below) which suggested that the impact of bLF was much greater among babies with low human milk intake (11% bLF, 21% controls). Although they do indeed show that, what is strange is that their analysis shows that LOS was much more frequent in babies with a high human milk intake, either with bLF (35%) or in their controls (39%), which is hard to understand. Another secondary analysis, of the data from ELFIN and the original Manzoni trial, showed similar reductions in LOS by bLF among breast-milk fed and formula fed, or mixed feeds babies. The reductions in LOS by bLF were very small and consistent with random variation in ELFIN. The interaction term was not significant, suggesting that the reduction in LOS was similar regardless of feed type.

The authors of the new study also note that their control frequency of sepsis was high, which is again true, a 40% incidence of LOS in a group of infants with a mean GA of 30 wks is extremely high. Having a higher baseline frequency of an abnormality will generally tend to make the impact of an intervention seem greater (see my recent posts on regression to the mean), but that doesn’t mean that such an impact would disappear completely when the incidence is lower.

One other difference that they do not mention is the source of bLF; the newly published trial used DicoPharm, just as did Manzoni. Akin’s study used the same product and also showed a reduction in culture-positive sepsis. Theresa Ochoa in her 2 studies used a product from Tatua ™ in the first study, derived from pasteurized milk, which had no effect on culture-positive sepsis, and a product from Friesland Campina in the other trial, which seems to be extracted by freeze-drying and not heat treated. The second trial showed a decrease in culture positive sepsis (from 11 to 8%, NS) not shared by the first study. Other studies either don’t mention the source of the bLF (Kaur et al) or I cannot obtain them as they aren’t in PubMed, or any other database that I can access (Liu, Tang, Dai). Another new study, from Egypt, randomized only formula fed infants (Ellakkany N, et al. Influence of bovine lactoferrin on feeding intolerance and intestinal permeability in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;184(1):30). They had an enormously high rate of LOS in the controls (60%) and a lower, but still extremely high, incidence in the bLF treated infants, 43.3%. The preparation they used was produced in Egypt, and I can’t find any details of how it was prepared. Finally I found one other trial, performed in Pakistan in infants with an average GA of about 34 weeks, (Ariff S, et al. Evaluation of Bovine Lactoferrin for Prevention of Late-Onset Sepsis in Low-Birth-Weight Infants: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2025;17(11)). with a product from Hilmar in the USA which appears to have been prepared from freeze-dried milk (and perhaps not heat treated), they had an 8% incidence of culture-positive LOS in controls, and a combined 6% in the 2 treatment groups (with 2 different doses of bLF); total n of about 300.

There are lab studies showing that pasteurization decreases the biologic activity of bLF. bLF is degraded by heat treatment, it aggregates, and bind iron less well (Remadevi R, Mead D. A Study on the Bioavailability of Lactoferrin under Pasteurisation at Different Conductivities and Solid Contents. Journal of Food Research. 2025;14(2)). It could well be that heat-treatment of milk, prior to extraction of bLF, causes sufficient structural changes in the molecule for it to no longer have the multiple beneficial effects on bacterial proliferation that have been documented. This might be one reason why donor human milk (which is always pasteurized, usually by Holder pasteurization, the only method approved by HMBANA) is less effective at decreasing NEC than Mothers own Milk.

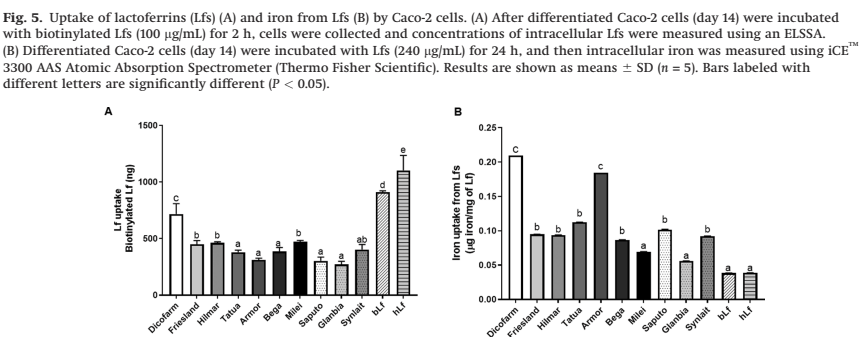

There are, however, known to be major differences in the biologic activity of different sources of bLF. One study examined 10 different bLF sources, and compared several different aspects of structure and activity between them, as well as their own bLF and human LF (Lonnerdal B, et al. Biological activities of commercial bovine lactoferrin sources. Biochem Cell Biol. 2021;99(1):35–46). There were major differences between bLF sources. As one example, they examined uptake of the LF by Caco-2 cells, and whether the LF transported iron into those cells

The details of what that means are not that important here (partly because my own understanding is limited, but also because it isn’t certain what this particular aspect has to do with their biologic effect of decreasing infections), but what this does show is that different sources of bLF are extremely different. They also found very variable degrees of contamination of the bLF product with other proteins, the Hilmar product, as one example “contains a relatively low concentration of Lf and relatively high concentrations of a-S1-casein, a-S2-casein, and J domain- containing protein”, whereas the Dicopharm product had lots of LF and relatively less of the other proteins.

I think, before we give up completely on bLF supplementation as a potential way to decrease LOS in the preterm, there is room for another study, investigating specifically the Dicopharm product, which has been consistently associated with decreases in culture-positive LOS. It may be that the story of bLF to prevent LOS still has a twist in the tale.

Pingback: Is this article trustworthy? | Neonatal Research